A Reflection on the Prologue of St. John’s Gospel

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

Opening Lines: A Reflection on the Prologue of St. John’s Gospel

(Isa 61:10-62:5, Ps 147:12-20, Gal 3:23-4:7, John 1:1-18)

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

Almighty God, who hast given us thy only-begotten Son to take our nature upon him, and as at this time to be born of a pure Virgin: Grant that we being regenerate, and made thy children by adoption and grace, may daily be renewed by thy Holy Spirit; through the same our Lord Jesus Christ, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the same Spirit, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Charles Dickens was a master of opening lines, perhaps not the master, but certainly a contender for the title as these examples show.

From A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way — in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on it being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities).

From A Christmas Carol:

Marley was dead, to begin with, there is no doubt whatever about that (Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol).

From David Copperfield:

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anyone else, these pages must show (Charles Dickens, David Copperfield).

I envy Dickens’ gift for beginnings, because I struggle with starting a story, a lesson, a sermon myself, because I know that the whole course of what follows is set by that first line, by that first thought. Imagine if A Tale of Two Cities had opened with this:

Life was pretty much then as it is now, only more so.

Would anyone have bothered to read the second line? And to borrow from another author, “Hi — How are ya? — my name’s Bob,” would be a poor alternative indeed for “Call me Ishmael.” Opening lines matter.

Now, if I am intimidated by the empty page, I can scarcely imagine the trepidation of the four evangelists — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — as they sat before a fresh parchment or spoke first words into the silence for a scribe to record. The Gospel, the good news of Jesus Christ: Where do we begin? What words are adequate for the task?

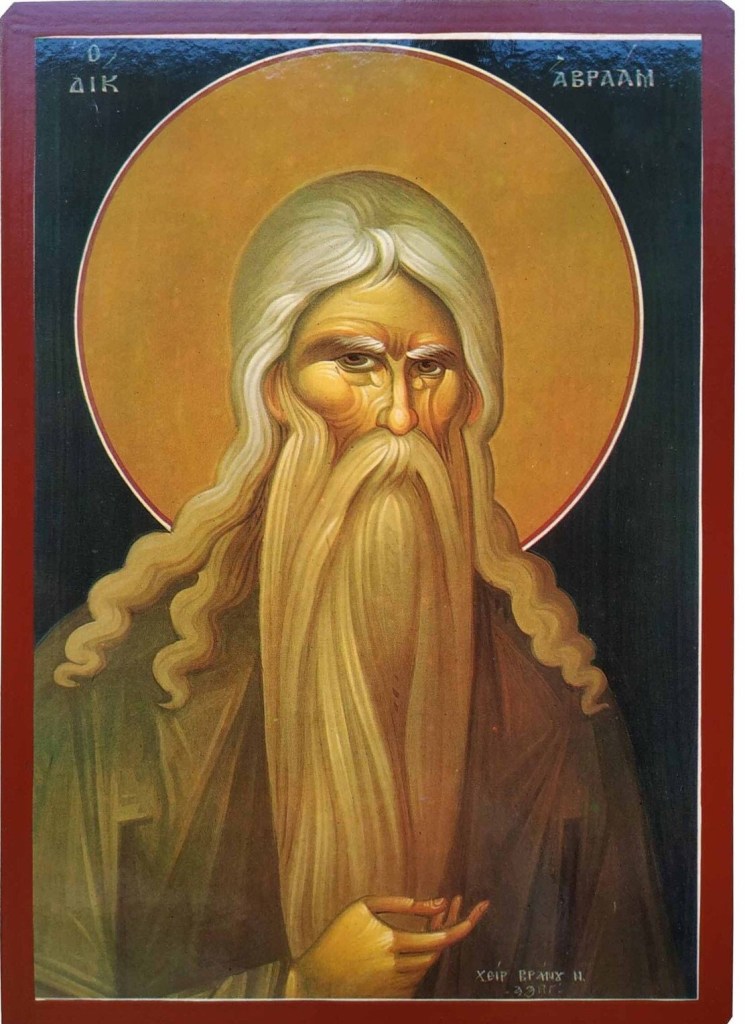

1 The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham (Matt 1:1).

St. Matthew begins with a genealogy. St. Matthew begins with Abraham and David because he wants to root his story in the ancient story of Israel, to show Jesus as the fulfillment, the climax of that story: not a bad opening.

1 The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.

2 As it is written in Isaiah the prophet… (Mark 1:1-2a).

St. Mark begins with a particular prophecy from Isaiah, a prophecy about a messenger who will come to prepare the way of the Lord, to make his paths straight, a prophecy fulfilled in John the Baptist. That is a catchy introduction.

5 In the days of Herod, king of Judea, there was a priest named Zechariah, of the division of Abijah. And he had a wife from the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth (Luke 1:5).

St. Luke, after explaining how and why he came to write the story at all, begins the tale proper with Zechariah and Elizabeth, the old and barren couple who miraculously will birth John the baptist, reminiscent of Abram and Sarai and their son Isaac. Well, you can’t go wrong with a little historical and symbolic context like that.

These three evangelists, each in his own way, each with his own opening line, root the Gospel in the story of Israel: calling, covenant, kingdom, prophets. That is the three. But what of St. John, the fourth evangelist? What of St. John the Theologian?

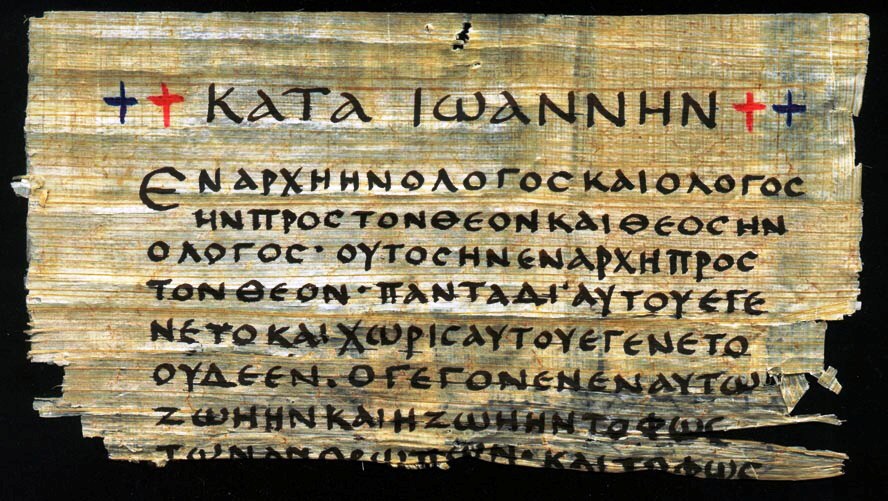

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God (John 1:1).

Before calling and covenant, before kingdom and prophets, even before the beginning of all things there was God, and it is with God that St. John starts his story, with God and with the Word. But, what is this Word of which the evangelist speaks? Perhaps, as in some Jewish thought, the Word may be identified with Wisdom as we find in Proverbs?

As Wisdom speaks:

22 “The Lord possessed me at the beginning of his work,

the first of his acts of old.

23 Ages ago I was set up,

at the first, before the beginning of the earth.

24 When there were no depths I was brought forth,

when there were no springs abounding with water.

25 Before the mountains had been shaped,

before the hills, I was brought forth,

26 before he had made the earth with its fields,

or the first of the dust of the world.

27 When he established the heavens, I was there;

when he drew a circle on the face of the deep,

28 when he made firm the skies above,

when he established the fountains of the deep,

29 when he assigned to the sea its limit,

so that the waters might not transgress his command,

when he marked out the foundations of the earth,

30 then I was beside him, like a master workman,

and I was daily his delight,

rejoicing before him always,

31 rejoicing in his inhabited world

and delighting in the children of man” (Prov 8:22-31).

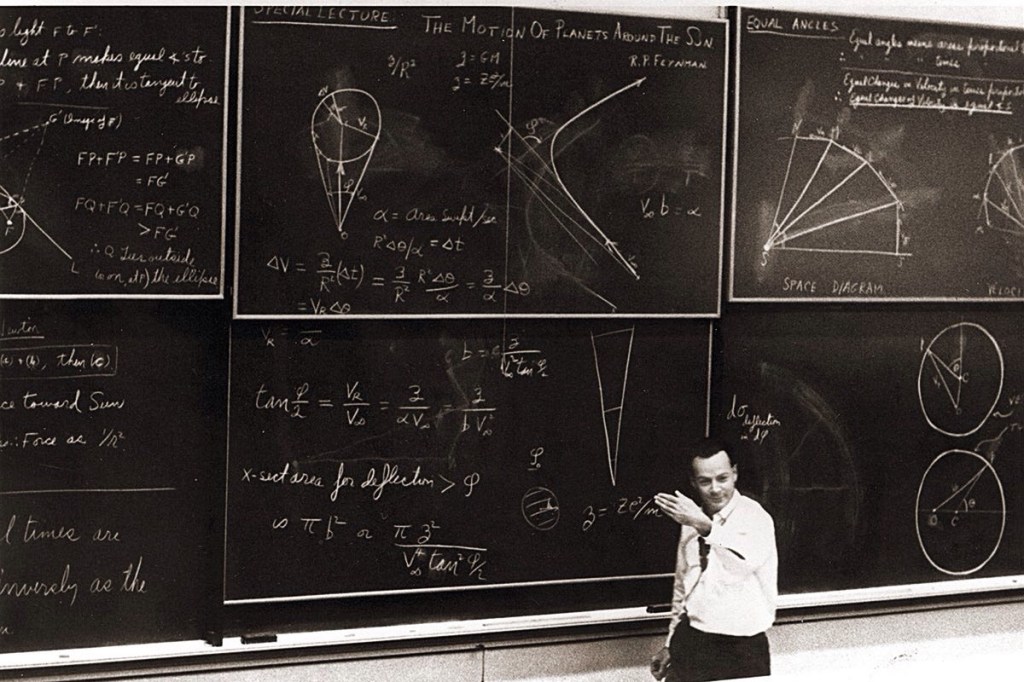

Or perhaps, as in Greek thought, the Word might be identified with the rational principle inherent in creation, with the reason we have cosmos/order and not chaos? This notion might even be implied in the original language where Word is λογος (logos). Mathematics is rational; it is logical (logos). Nature is amenable to scientific discovery and explanation because it is rational; it is logical (logos). Perhaps the Word is that abstract principle of logic which permeates all of creation.

But no, neither of these descriptions — neither Wisdom nor Logic — encompasses nor exhausts St. John’s meaning:

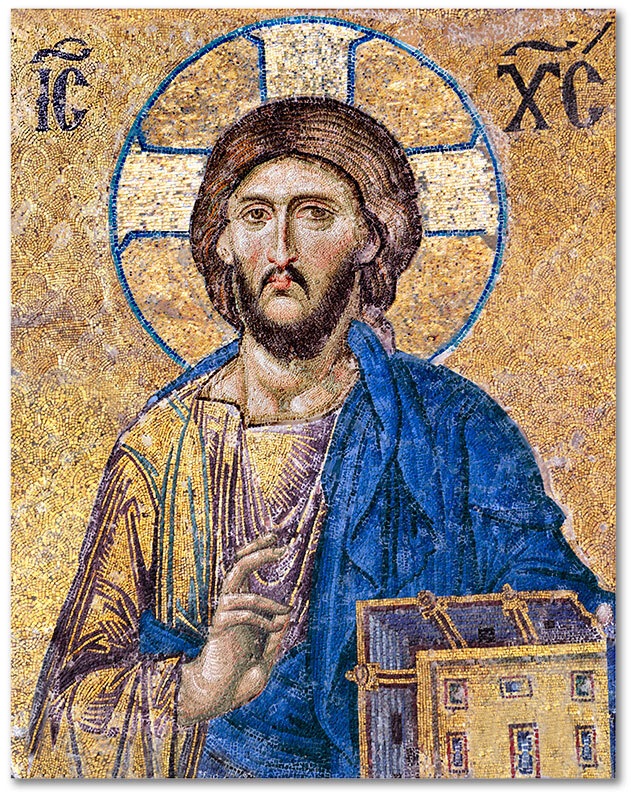

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God (John 1:1).

The very last conviction St. John expresses in that opening line is the one that makes all the difference, the one that makes St. John’s opening line distinct from all others: and the Word was God — not just the wisdom of God, not merely the logic of God, but fully God. If that does not startle us and confound us, then we are not paying attention. Before anything at all was brought into being, there was God and there was the Word — pre-existent, in some sense beyond existence itself, not things like other things that will come to be. And the relationship between God and the Word is not rendered transparent by St. John’s language; it is rendered mysterious. If the Word is with God, how is the Word God? This statement made about humans would be nonsense, mere gibberish. And John was there at the start. And John was with Bob, and John was Bob. Spoken about men, this is the opposite of logos; it is mere babbling. Yes, precisely. It cannot be said about men. But, it can be said about God and must be said about the Word; it is a mystery, but it is not nonsense. In some sense yet to be worked out by St. John — in some sense yet to be worked out by the Church for generations — between God and the Word there is both differentiation (the Word was with God) and perfect identification (the Word was God).

The Word was with God and the Word was God from before the beginning. And again, with these opening words, St. John plunges us into mystery: In the time before there was time? In the place before there was place? This is obscure to us; for us there is only darkness in that time of no time and disorientation in that place of no place. But for God, for the Word? No, they precede time; they encompass space.

So, St. John moves on:

2 He [the Word] was in the beginning with God. 3 All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. 4 In him was life, and the life was the light of men. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it (John 1:2-5).

The Word, who was with God and who was God from before the beginning, became the beginning of all things. The late Carl Sagan, astronomer and popularizer of science not least through his book and television series Cosmos wrote:

The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us — there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries (Carl Sagan, Cosmos).

That is a lovely piece of writing, even reminiscent of St. John’s Prologue, but it is not science and it is not true. The Cosmos is not all that is or was or ever will be. The cosmos was spoken into being by the Word who from before the beginning of all things was with God and who was God and through whom all things — this cosmos and even, if there be others — were made. All created things that you see, all created things that you do not see, all these things exist. But the Word, the Word in the language of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Word being God is ipsum esse subsistens, the very act of “to be,” the ground of being, the One who cannot not be, the One in whom and through whom and for whom all things exist and have their contingent being. This is a great mystery, and even our feeblest contemplations of it stir us not just with a tingling in the spine or a catch in the voice, but with life itself, with light shining in the darkness, with a light that penetrates and illumines the darkness and which cannot be overcome by the darkness.

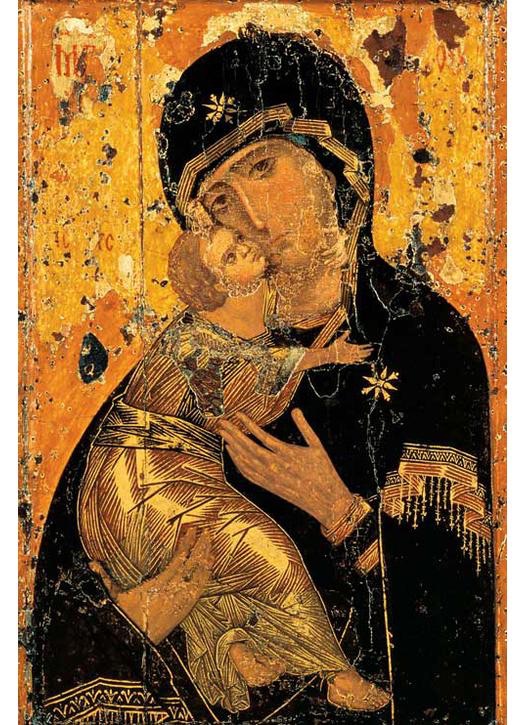

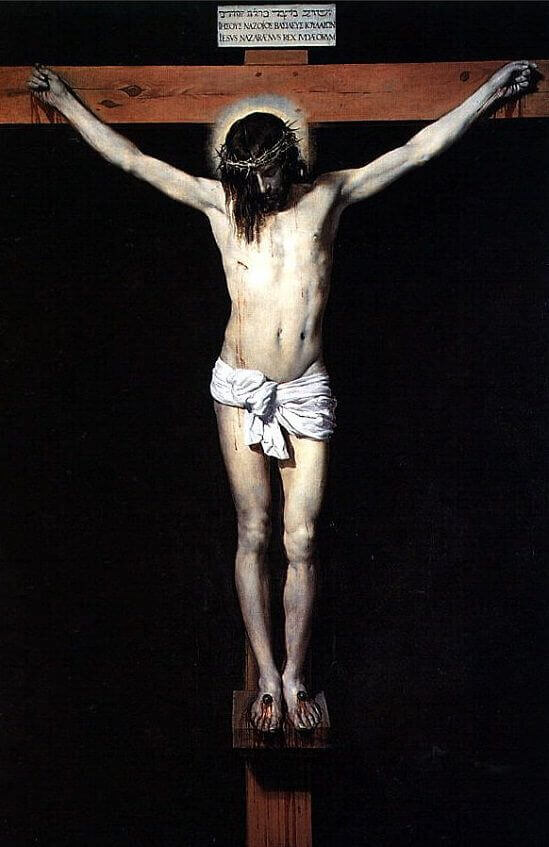

Though we are already awash in mysteries, there is yet more, always more. This Word who from before the beginning was with God and who was God, this Word who is beyond existence and who called into being everything that does exist, this Creator Word, entered his creation as creature. And the Word did so without ceasing to be the Word, without ceasing to be with God and to be God. And that reality is so mysterious, so luminous, so holy that we usually kneel in worship when we read its description by St. John:

14 And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us +, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth (John 1:14).

The mystery of the Cosmos pales in comparison to this. This Word is…well:

15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. 16 For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. 17 And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together. 18 And he is the head of the body, the church. He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, that in everything he might be preeminent. 19 For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, 20 and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross (Col 1:15-20).

This Word who was in the form of God — who was with God and who was God — this Word:

7 emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men (Phil 2:7).

And though the Word emptied himself of all his divine prerogatives, he did not and could not empty himself of himself; he did not and could not cease to be what he is from all eternity: the Word who is with God and who is God. And so, when the Word became flesh to dwell among us, we saw glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth. We saw God with skin on, not skin as a suit to be donned and doffed at will, but humanity as assumed into the divine nature unto the ages of ages, as human nature drawn into the divine life and united with the divine nature in One Person, in the Word made Flesh, in the God-man Jesus Christ. The Word became flesh. God descended to earth and humanity ascended into heaven. He is the perfect image, the perfect icon, of the invisible God because he is God himself. All that we know of God, we know through him, because “no one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known” (John 1:18).

Now, for two final mysteries in this great Prologue of St. John’s Gospel, these great opening lines.

The Word became flesh and dwelt — pitched his tent — among us, the Word who is life and light. And the world preferred death, the world chose darkness instead.

10 He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world did not know him. 11 He came to his own, and his own people did not receive him (John 1:10-11).

Even when a man was sent from God — John the Forerunner — who came as a witness to the Light that all might believe through him, they did not recognize, they did not receive the Word made flesh: not all of them, not the people prepared through covenant, through Law, through Kings and prophets. But, here and there, in fits and starts, now and then a few did receive him, did hear the Word, did see the light, did find life in him. And,

12 [But] to all who did receive him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God, 13 who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God (John 1:12-13).

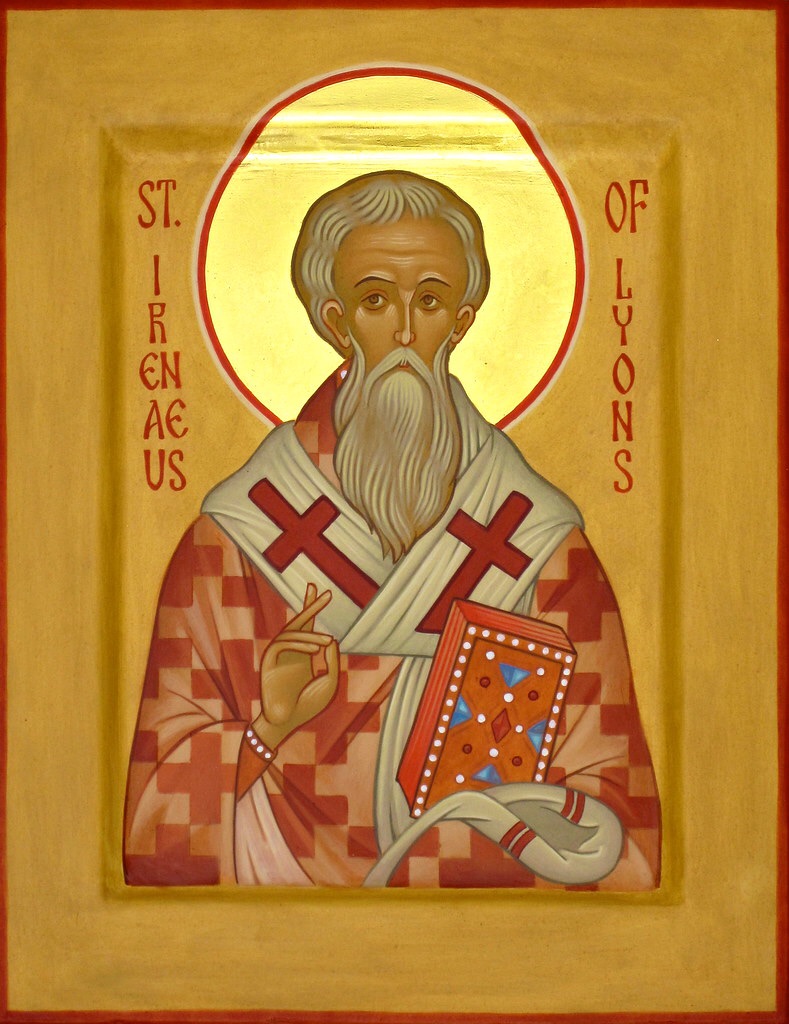

Here we are getting near one of the deepest mysteries of all. Why did the Word who was with God and who was God become flesh to dwell among us as one of us? In the words of St. Irenaeus of Lyon:

For it was for this end that the Word of God was made man, and He who was the Son of God became the Son of man, that man, having been taken into the Word, and receiving the adoption, might become the son of God (Irenaeus, Against Heresies (Book III, Chapter 19.1)).

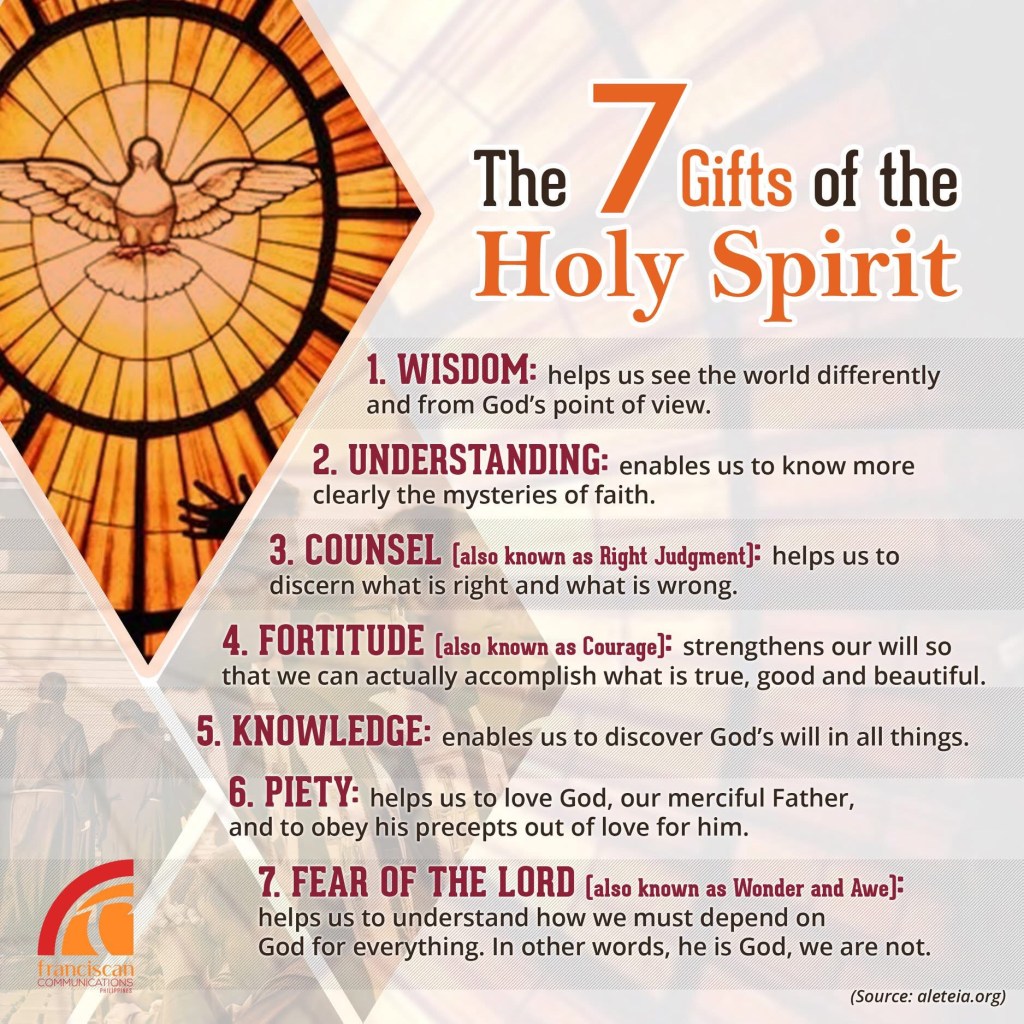

In paraphrase, He, the Word, became what we are so that we might become what he is: not divine by nature, but a participant in the divine nature, and thus the sons and daughters of God by the grace of adoption — not by a legal fiction, but by the indwelling Holy Spirit who unites us to the Word and transforms us into the likeness of the Son.

Is there a deeper mystery than this, that from before the foundations of the world the foreknowledge and will of God included the creation of human beings who would one day bear his own image and be called — be made — his own sons/daughters, and that through the incarnation of the Word?

This theme is close to the heart of St. John. In his first epistle he wrote:

1 See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are. The reason why the world does not know us is that it did not know him. 2 Beloved, we are God’s children now, and what we will be has not yet appeared; but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is. 3 And everyone who thus hopes in him purifies himself as he is pure (1 John 3:1-3).

Through the incarnation of the Word; through his life, death, resurrection, ascension, and with the descent of the Holy Spirit; through faith and baptism; through word and sacrament and prayer and repentance; through the grace of God we are not only called children of God, but so we are. And while now we bear that image so incompletely, so imperfectly, when the Word, our Lord Jesus Christ, appears yet again among us, when we see him truly as he is, we will be like him.

Opening lines matter, and, for my money, St. John — not Dickens — was the master.

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. 4 In him was life, and the life was the light of men. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

14 And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.

Amen.