Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

Romans, Part 2: Pears, Vines, and the Gospel

We begin this morning with a prayer from the The Solemn Collects of Good Friday.

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray for the Jewish people: that the Lord our God may look graciously upon them, and that they may come to know Jesus as the Messiah, and as the Lord of all.

Almighty and everlasting God, you established your covenant with Abraham and his seed: Hear the prayers of your Church, that the people through whom you brought blessing to the world may also receive the blessing of salvation, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (BCP 2019, p. 570).

As I am preparing this post for publication, Israel and the United States are engaged in join military action against Iran. And, it is only in recent days that a tenuous “peace” of sorts has prevailed in Gaza following months of Israel’s relentless military action against the Palestinians there. Opinions are divided on both these actions and I know some for whom the foregoing Solemn Collect is difficult to pray, not theologically, but viscerally. Here it is important to distinguish between the political state of Israel and the Jewish people. This prayer is offered not for the former — the state of Israel — but for the latter — the Jewish people. That we single this people out for prayer simply acknowledges their unique place in salvation history, a place that St. Paul insists is not over. The Jews are our fathers and mothers in the faith, or perhaps our elder brothers and sisters, but family nonetheless. And we pray for our family even if we are, for the moment, estranged.

Summary of Romans, Part 1 (Chapters 1-6)

Grab on and hold tight for this breakneck summary of last week’s lesson, Romans, Part 1 (chapters 1-6).

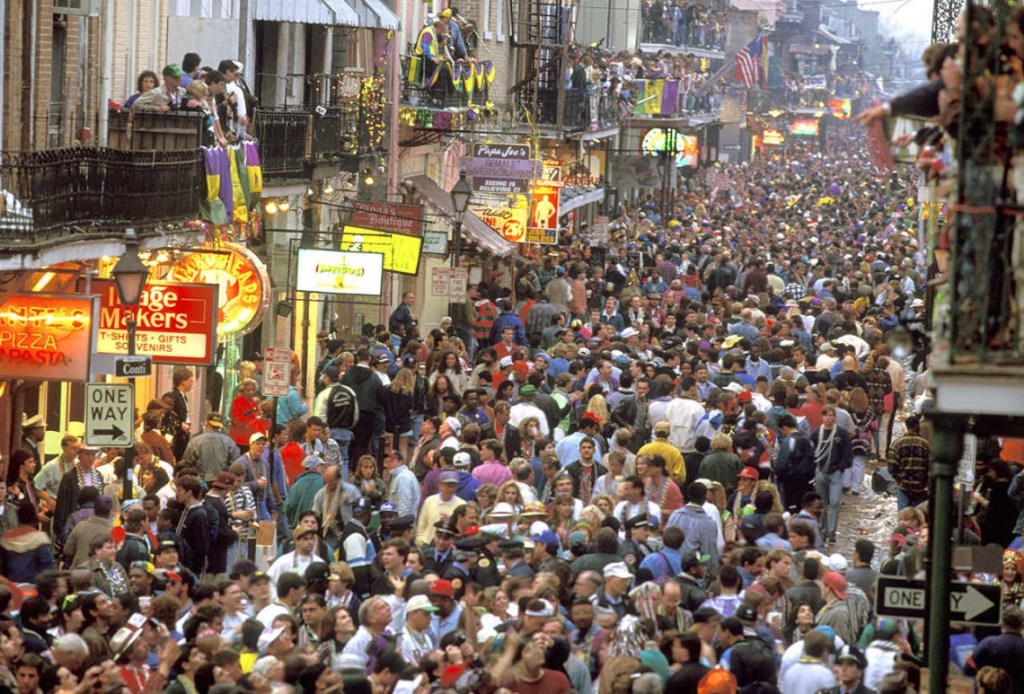

Paul is writing a fund raising letter of sorts to the church(es) at Rome. He wants to go to Spain and he is hoping to use Rome as his home base of support for that mission; he needs a staging area (a home church) and financial support. Since the church(es) at Rome either do not know him or perhaps know him only by his reputation as a troublemaker, Paul writes his fund raising letter as a theological summary of his presentation of the Gospel, and as a thorough introduction of himself and his message. But, a second issue is never far from his mind: the relationship between Jews and Gentiles. How does Israel — who seems to reject Christ wholesale — factor into God’s plan for the redemption of all things? Is there still any place for the Jews in the Gospel, or is Israel now an outdated dead end replaced by the Gentiles, God’s Plan A gone hopelessly wrong?

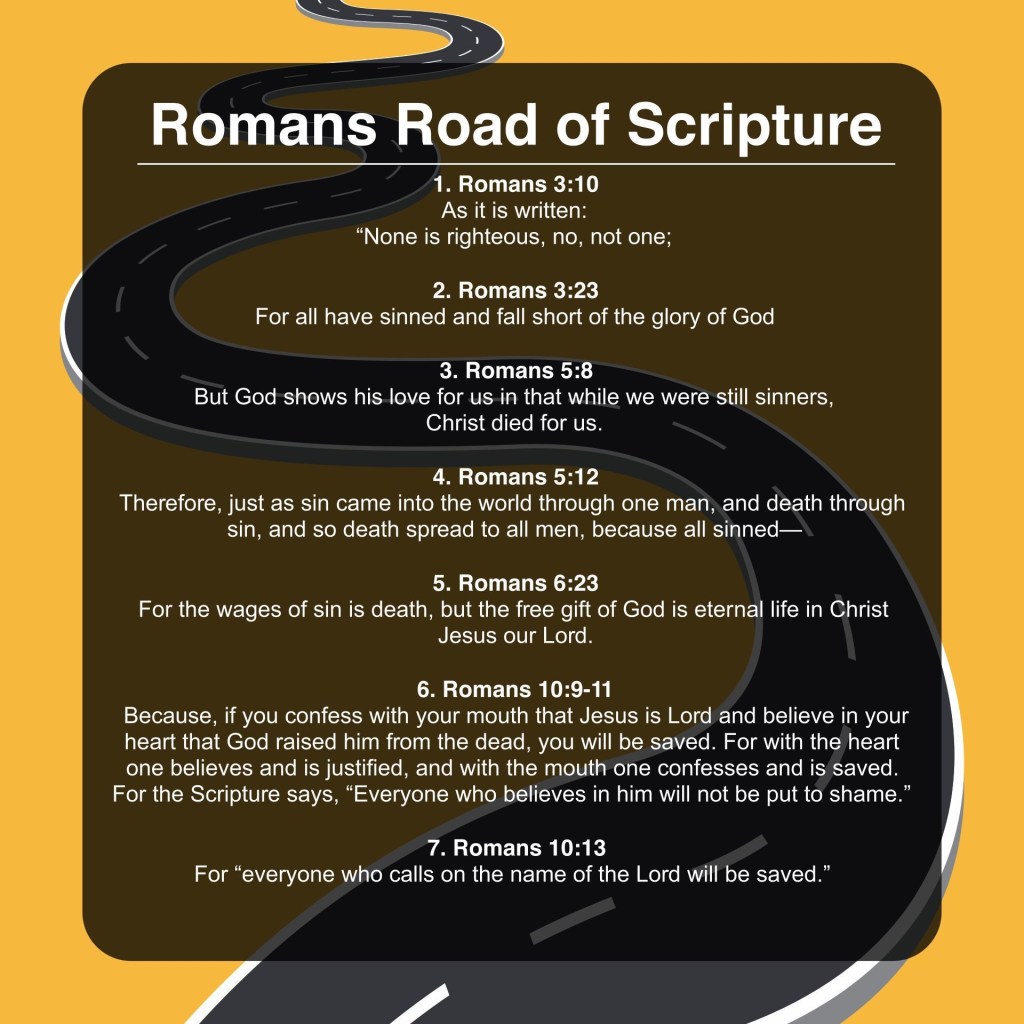

Paul starts the letter with the assertion that all men, Jews and Gentiles alike, are in bondage to sin and are under God’s righteous judgment. The Jews cannot stand on the Law to save them because they did not and do not keep it. The Gentiles cannot stand on the natural law to save them because they did not and do not keep it. Paul writes:

For we have already charged that all, both Jews and Greeks, are under sin, as it is written:

“None us righteous, no not one;

11 no one understands; no one seeks for God” (Rom 3:9b-11).

So much for the bad news. Now for the good news, the Gospel.

21 But now the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from the law, although the Law and the Prophets bear witness to it— 22 the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe. For there is no distinction: 23 for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, 24 and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, 25 whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith (Rom 3:21-25a).

The good news is that God has taken the initiative to deliver us from sin and its wages, death, through the faithfulness of Christ and through our faithfulness to Christ. Though the Law served its purpose to bring us to Christ, we dare not now go back to it or add it onto Christ. It is faith, and not the Law, that lies at the heart of the Gospel. So much for the summary of Part One.

Pears and the Law

Now to part two of our series, beginning with Romans 7. Paul wants to drive home an important point about the Law, that our failure to keep it was not the Law’s fault, but was the result of sin in us that was stirred up by the Law and which carried us along with it. We cannot blame the Law for our condition; sin is at the root of it, sin that enslaves us.

Now, rather than turn directly to St. Paul here, I want to turn to St. Augustine, to a brief passage from his Confession.

It is certain, O Lord, that theft is punished by your law, the law that is written in men’s hearts and cannot be erased however sinful they are. For no thief can bear that another thief should steal from him, even if he is rich and the other is driven to it by want. Yet I was willing to steal, and steal I did, although I was not compelled by any lack, unless it were the lack of a sense of justice or a distaste for what was right and a greedy love of doing wrong. For of what I stole I already had plenty, and much better at that and I had no wish to enjoy the things I coveted by stealing, but only to enjoy the theft itself and the sin. There was a pear-tree near our vineyard, loaded with fruit that was attractive neither to look at nor to taste. Late one night a band of ruffians, myself included, went off to shake down the fruit and carry it away, for we had continued our games out of doors until well after dark, as was our pernicious habit. We took away an enormous quantity of pears, not to eat them ourselves, but simply to throw them to the pigs. Perhaps we ate some of them, but our real pleasure consisted in doing something that was forbidden.

Look into my heart, O God, the same heart on which you took pity when it was in the depths of the abyss. Let my heart now tell you what prompted me to do wrong for no purpose, and why it was only my own love of mischief that made me do it. The evil in me was foul, but I loved it. I loved my own perdition and my own faults, not the things for which I committed wrong, but the wrong itself. My soul was vicious and broke away from your safe keeping to seek its own destruction, looking for no profit in disgrace but only for disgrace itself (St. Augustine, Confessions, Penguin Books (1961), Book II, Chapter 4, pp. 47-48).

Notice what St. Augustine said about theft. He didn’t steal the pears because he was hungry; he had no need of them. He stole the pears because God’s law condemned theft and that stirred up in him the desire to steal. He stole only to enjoy the theft and the sin. This paints man into a corner, and St. Augustine presents the dilemma so well. The Law tells us what is wrong, but it does not and cannot empower us to refrain from the wrong. Instead, sin takes advantage of the Law and stirs in us the desire to do evil. We are schizophrenic; we have a divided mind. It you have ever been near a “Fresh Paint” sign you know exactly what St. Augustine experienced. You had no desire to touch that wall until you saw the sign; it stirred up the desire in you and you seemed powerless to resist.

Now to Paul and Romans 7. He says — using a particular example — that he never coveted until he received the Law that says, “You shall not covet.” Then, the sin to which he is enslaved stirred up the covetous desire and he seemed powerless to resist: Augustine before Augustine. He didn’t want to disobey the Law, but through the Law, sin had him in its grasp and compelled him to act contrary to his true desire. Then comes the famous passage that you know well:

14 For we know that the law is spiritual, but I am of the flesh, sold under sin. 15 For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. 16 Now if I do what I do not want, I agree with the law, that it is good. 17 So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. 18 For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. 19 For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. 20 Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me.

21 So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. 22 For I delight in the law of God, in my inner being, 23 but I see in my members another law waging war against the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. 24 Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death (Rom 7:14-24)?

There is the great human dilemma. We know the Law is good. We want to obey it. But sin has slipped in through the “back door” when the Law was given and has enslaved me; it has taken advantage of the Law to kill me. Paul’s cry is real: “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death” (Rom 7:24)? And that question leads us to the heart of Romans and one of the most magnificent chapters in all of Scripture: Romans 8.

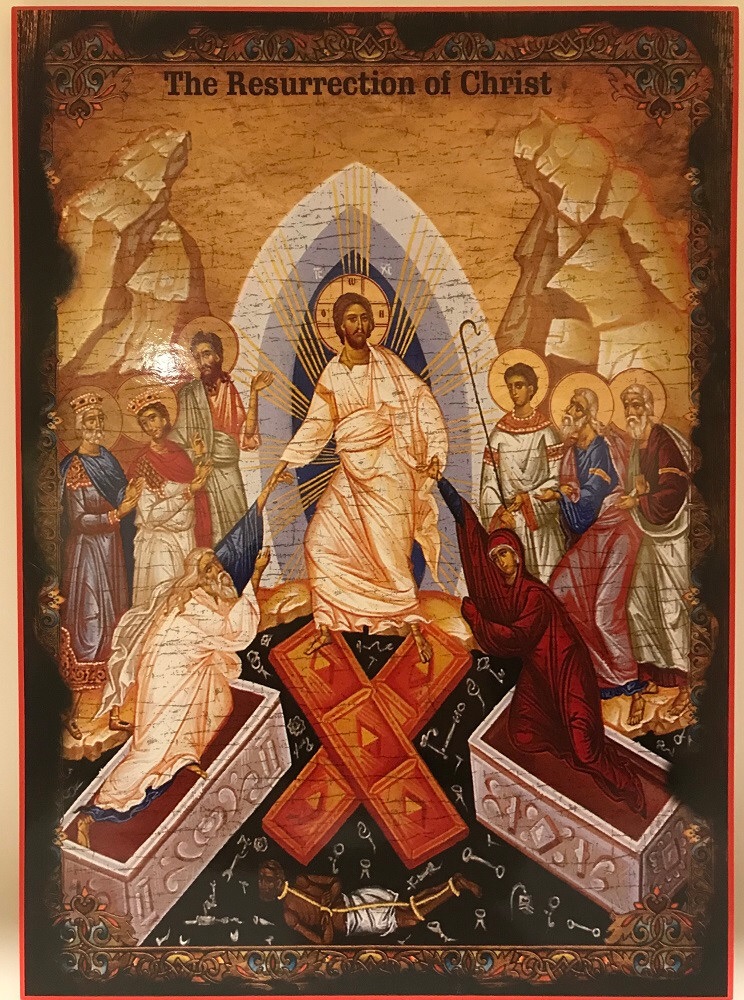

Freedom!

The first four verses say it all in dense summary.

1 There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. 2 For the law of the Spirit of life has set you free in Christ Jesus from the law of sin and death. 3 For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, 4 in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.

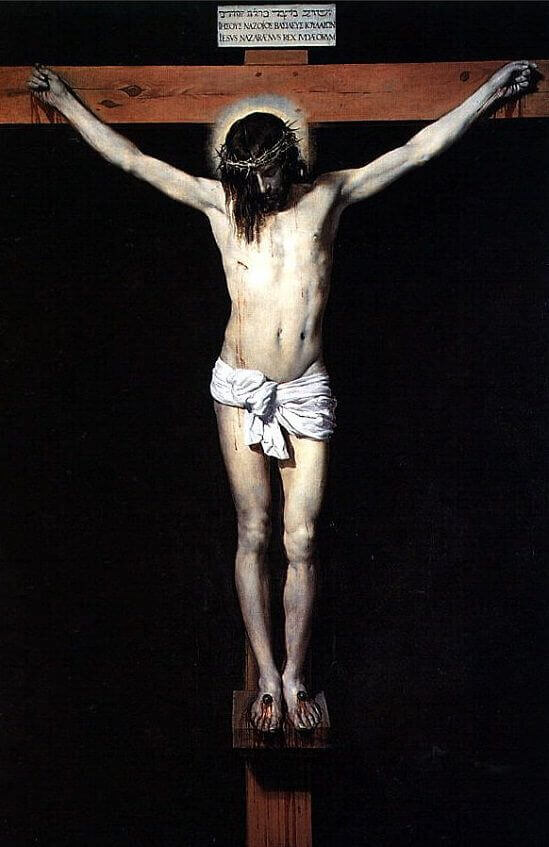

God, in Christ, has done what we could never do: he has freed us from slavery to sin by condemning sin in the flesh of Jesus. This is crucial because it lies at the heart of what we call “the atonement.” Jesus, who knew no sin and owed no debt to it, nevertheless drew all the sin of the world to himself, took it upon himself becoming the epitome of sin for our sake (2 Cor 5:21). Then he bore that sin to the cross and God condemned sin in the flesh of Jesus to fulfill the curse of the Law (see Deut 28:15-68): condemned sin in the flesh of Jesus. Think of sin as a spiritual parasite and the body of Jesus as the willing host. Destroy the host, and the parasite cannot survive. Jesus offered himself as the host knowing that with the destruction of his flesh, parasitic sin would also be destroyed. It is not without significance that we call the bread of the Eucharist the “host,” from the Latin hostis meaning “victim.”

Jesus gave himself as the host for sin, as the one who took upon himself all the sin of the would, and offered himself as a willing victim so that sin might be destroyed. Now, when I speak of sin being destroyed, I mean its power over us has been destroyed and the dilemma that both Saints Augustine and Paul spoke of has been resolved. While we may still freely choose to sin, we are not compelled to do so as slaves. Through Christ, we are free and, even more, we are now empowered by the Spirit, not enslaved by the flesh.

Our freedom is just the beginning. The purpose of God is to restore all things in heaven and on earth — our bodies and all of creation — to free all things from the corrupting power of sin. This is an already-not yet moment in the story. Christ has already won the victory over sin and has freed us from death, the wages of sin. But, sin has not yet been eliminated as a real possibility, nor have its consequences. Because that has not yet been fully implemented we still suffer and groan in the flesh. And not only we, but all of creation groans. So, Paul gives us this great promise and assurance:

18 For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us. 19 For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. 20 For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. 22 For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. 23 And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. 24 For in this hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what he sees? 25 But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience (Rom 8:18-25).

So, while the work that Christ did was finished on the cross, its outworking is not yet complete. It is a future reality, and we have a part to play in its coming to full fruition. Part of that work — a significant part of that work — is our prayer, our hope, our confidence in the goodness and love of God. Listen to St. Paul’s words:

26 Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness. For we do not know what to pray for as we ought, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words. 27 And he who searches hearts knows what is the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for the saints according to the will of God. 28 And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose (Rom 8:26-28).

31 What then shall we say to these things? If God is for us, who can be against us? 32 He who did not spare his own Son but gave him up for us all, how will he not also with him graciously give us all things? 33 Who shall bring any charge against God’s elect? It is God who justifies. 34 Who is to condemn? Christ Jesus is the one who died—more than that, who was raised—who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us. 35 Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or danger, or sword? 36 As it is written,

“For your sake we are being killed all the day long;

we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered.”

37 No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. 38 For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, 39 nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (Rom 8:31-39).

Paul, Israel, and the People of God

Paul has been accused, by the Judaizers, of antinomianism — of rejection of the Mosaic Law — and even of being antisemitic in the sense of denying the central and eternal role of Israel in God’s redemptive purpose, of saying that God’s purpose for Israel failed and that he has now abandoned the Jews in favor of the Gentiles. In Romans 9-11, Paul defends himself against those charges and explains his understanding of the role of Israel and the relationship between Jews and Gentiles in the Gospel. It is a long and complex argument. I can only try to outline the major points of the argument as simply as I can while passing over some points — important ones — that might distract us from the main line of thought. That will be deeply unsatisfying to some of you, and I understand that. My only defense is the shortness of time we have for the task at hand.

Paul starts with his love for Israel — he would trade his life for theirs — and with an affirmation of the central role that Israel has played in God’s plan: adoption (election), glory, covenants, law, worship, promises, patriarchs, and ultimately Christ himself — all Jewish. Paul is neither antinomian nor antisemitic. See Rom 9:1-5.

Nor has God’s plan for Israel failed just because most of Israel has failed to see Jesus as messiah. True Israel, faithful Israel, has always been a subset of the descendants of Abraham and never the whole lot. The covenant came through Isaac and not Ishmael, through Jacob and not Esau. God has always worked with a Jewish remnant. That is not a failure; that is God’s sovereign choice. See Rom 9:6-29.

Now, I must leave the text for just a moment for an excursus on election and God’s sovereign choice, because this is a place where Paul’s argument has been distorted. Paul is talking about the instrumental election of a remnant of Israel through which God will accomplish his plan of redemption for all people. That is a dense statement, so let’s unpack it a bit. This passage is not about God selecting some individuals for salvation and some for damnation. It is not about individual predestination though som want to make it about that. It is all about which group of people God chooses to use to accomplish his purpose for the good of all. Just because a group is not chosen for a particular purpose does not imply that that group is eternally rejected by God. God may and does, according to his wisdom and righteousness, choose certain people, certain groups, to be his instruments of salvation and judgment. But that does not mean that those not so chosen are destined for destruction: more about this in Paul’s discussion of Israel. Now, back to the text and to Paul’s argument.

How is it — and how is it fair — that the Jews who pursued righteousness through the Law missed it while the Gentiles who did not pursue righteousness have found it through faith in Christ? Paul answers that faith is the key. Yes, the Jews — some of them and to some extent — kept the Law, but they did so as if by their work they might obligate God to declare them righteous, in sort of a theological quid pro quo. But righteousness is found only in Christ and only through faith: “For Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Rom 10:4). See Rom 9:30-10:13 for the extended argument.

Because of this, there is no distinction between Jews and Gentiles in terms of access to God. There are advantages of being a Jew in terms of having a long history of engagement with God, in terms of the glory of being chosen and caught up in his purpose. But in terms of the righteousness of God? No.

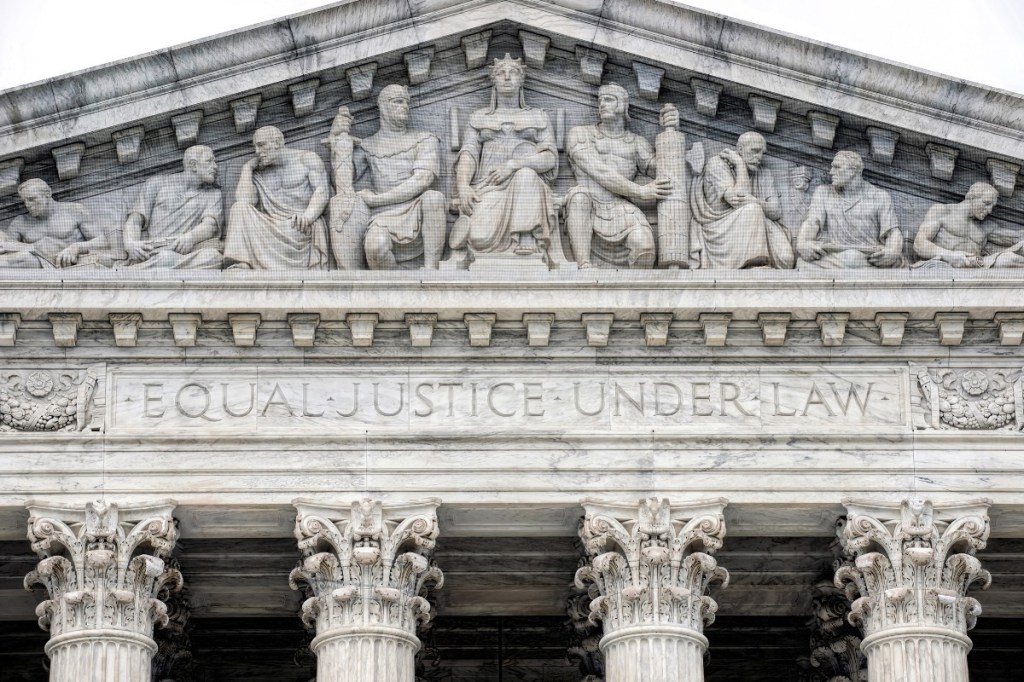

10 For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved. 11 For the Scripture says, “Everyone who believes in him will not be put to shame.” 12 For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; for the same Lord is Lord of all, bestowing his riches on all who call on him. 13 For “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Rom 10:10-13).

Well, what about those Jews that God has not chosen in this moment, in other words, what about those Jews who reject Jesus? Has God then rejected them? Are they no longer part of his purpose? This is where Paul’s argument get really dicey for us. It is where we are thrown back on the providence of God and on his loving mercy and on his plans, the details of which are opaque to us. It is the part of Paul’s argument that he grasps in principle, but even so struggles to articulate fully, so that at the end of it, recognizing the human inability to fully penetrate the mind and will of God, Paul resorts instead to humble doxology, to praise:

33 Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

34 “For who has known the mind of the Lord,

or who has been his counselor?”

35 “Or who has given a gift to him

that he might be repaid?”

36 For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen (Rom 11:33-36).

Now, to the argument. God has preserved for himself a remnant of faithful Israel, those who have seen and believed that Jesus is the messiah; these Paul calls the elect. As for the rest:

7 What then? Israel failed to obtain what it was seeking. The elect obtained it, but the rest were hardened, 8 as it is written,

“God gave them a spirit of stupor,

eyes that would not see

and ears that would not hear,

down to this very day” (Rom 11:7-8).

Understand that hardening means that God has affirmed the free choice of an individual or a people and has made them more resolute in those choices. It is not an arbitrary act of God, but rather God saying “yes” to the exercise of human will and choice. Remember that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart only after Pharaoh had done so himself. God’s hardening is God’s saying yes. But then God uses those with hardened hearts for his own salvific purposes, again, as with Pharaoh. The hardening of the heart of much of Israel was for the sake of the Gentiles. It is through their hardening of heart that God made way for the Gentiles to be receptive to the Gospel. We see that writ small in Paul’s own ministry. He went to the synagogues first in each town. Only when the Jews had hardened their hearts against the Gospel did Paul turn to the Gentiles. Why the hardening of most of Israel was necessary and how that works in detail — as far as as I’m concerned, God only knows. What Paul does give us, not by way of explanation but by way of analogy, is the image of an olive tree and grafted branches.

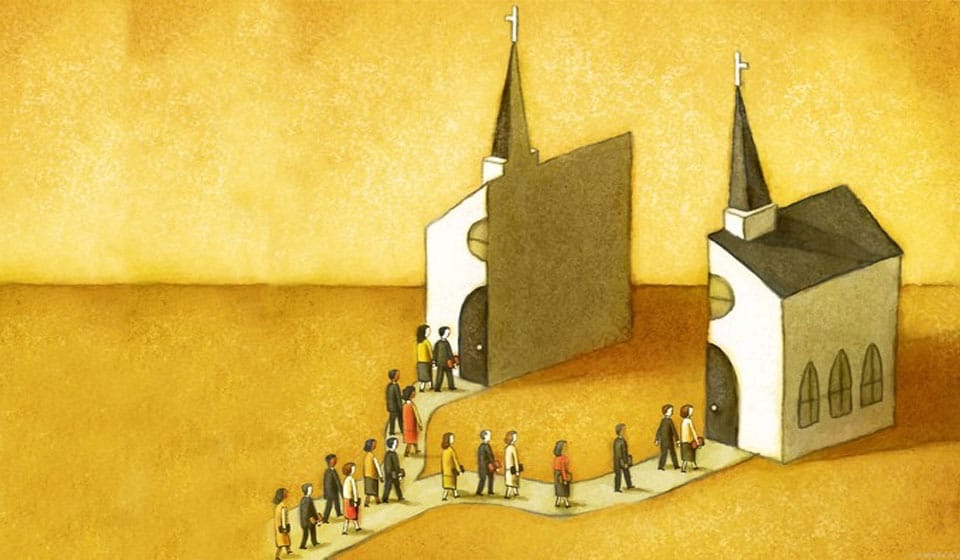

Think of an olive tree — Israel — with ancient roots: Abraham and the covenants, Moses and the Law, the prophets. There are some branches of the tree — the Jews with hardened hearts — that are broken off to allow room for wild olive shoots — believing Gentiles — to be grafted into the tree, to be nourished by and to share in the life of the rootstock. Note the implication here: the Gentiles do not receive the blessings of God apart from Israel, but by becoming a part of Israel through faith in Christ. God has not abandoned the Jews by including the Gentiles. God has made the Gentiles part of Israel so that they may share in the fullness of all God’s promises to Israel realized in, fulfilled through, Jesus Christ. The Gentiles dare not be arrogant about this, thinking that God has rejected Israel in their favor. They, too, can be broken off to make room for others.

What comes next, the completion of Paul’s argument, is a deep mystery. The hardening of the Jews is partial in scope and time. At some point — when the fullness of the Gentiles have been grafted in — the hardening will have achieved God’s purposes and it will be lifted. At that time mercy will again be offered to all. Those Jews who embrace Christ will be grafted back into the tree and in that way all Israel — that is, all believing Jews and Gentiles, all those who accept Christ as messiah and savior — will be saved. Jews and Gentiles belong together and are made one in Christ. See Romans 11:25-36. It is for that we pray. There is much more in chapters 9-11; we have just scratched the surface. But, I hope this will give you a helpful overview of Paul’s argument, on his own terms, so that these chapters will make better sense when you read them prayerfully and thoughtfully.

Now, in the little time remaining, we will look at some practical implications of all that has gone before. How, then, were the Romans to live? How are we to live?

Life in the Church

It may be tempting to divide each of St. Paul’s letters into two sections: theology first, followed by right living — the practical stuff. But, I think that misunderstands Paul who sees the Church as the advanced guard of the age to come, a living signpost pointing toward the renewal of all things in Christ. If I might say it this way, the Church is living, incarnational theology, theology with flesh on. The Church is what theology looks like lived out. So, there is no real distinction between the two sections of Paul’s letters. We are all theologians in the sense that the Church is called to live out its theology.

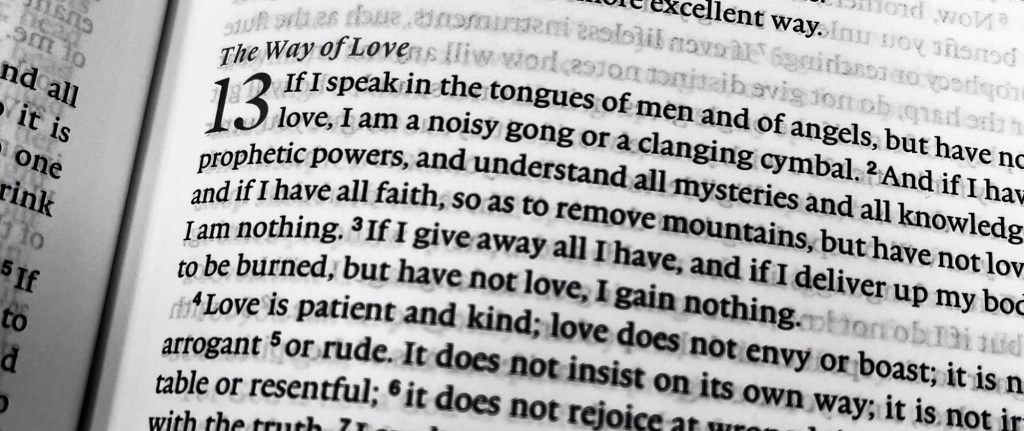

Now, I am really going to go far out on a limb. I’m going to try to summarize the heart of St. Paul’s theology, lived out in the Church, in a single sentence:

Through the redemptive work of Christ, received by faith, all those in Christ — without distinction — all those in Christ belong at the same Table, and all must live in love, one for another.

It is a clunky sentence, and others may do better, but it gets at the heart of St. Paul’s deepest convictions: the centrality of Christ, the sufficiency of true faith, the necessity of unity in the Church, and the primacy of love.

I have chosen one passage — that is all time will permit — that exemplifies this living theology, Rom 12:9-21. With this, I’ll bring this lesson to a close.

9 Let love be genuine. Abhor what is evil; hold fast to what is good. 10 Love one another with brotherly affection. Outdo one another in showing honor. 11 Do not be slothful in zeal, be fervent in spirit, serve the Lord. 12 Rejoice in hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer. 13 Contribute to the needs of the saints and seek to show hospitality.

14 Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them. 15 Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep. 16 Live in harmony with one another. Do not be haughty, but associate with the lowly. Never be wise in your own sight. 17 Repay no one evil for evil, but give thought to do what is honorable in the sight of all. 18 If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all. 19 Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” 20 To the contrary, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” 21 Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good (Rom 12:9-21).

There is Paul. There is his understanding of the Gospel. The question for the Roman Christians is simple: Can you, will you, embrace and support this Gospel? That, of course, is still the question.

Amen.