Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John Roop

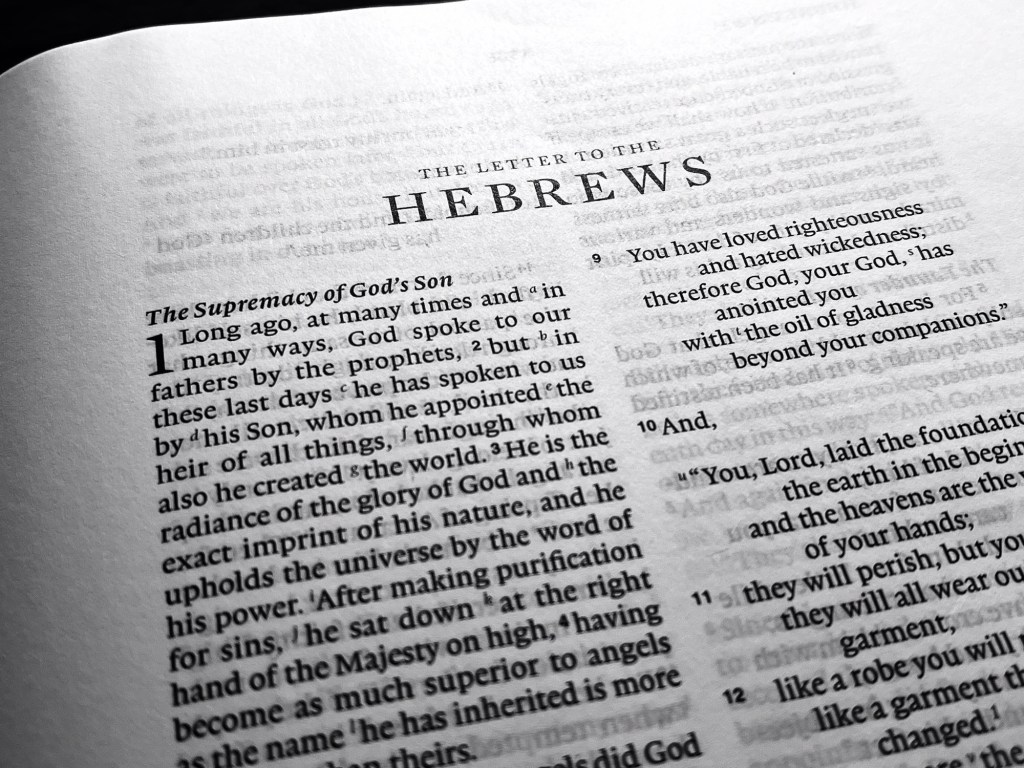

Hebrews 11-13: Our Superior Response

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

Grant us, Lord, not to be anxious about earthly things, but to love things heavenly; and even now, as we live among things that are passing away, to hold fast to those that shall endure; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Introduction

When I first began teaching high school nearly thirty-five years ago, teachers were required by the state to use the Tennessee Instructional Model to plan and deliver our lessons; it gave a uniform structure and format to all instruction. I certainly used it … when I was being evaluated by my administrators, and then I largely forgot about it every other day in the school year. In all fairness, though, it did sharpen the focus of a lesson by having the teacher complete this statement at the outset: By the end of this lesson the student will know _____ and be able to do _____. That statement emphasized the twofold nature of student-centered education as the state envisioned it: to know and to do. It was not a successful lesson if the teacher only provided information and the student received it. Knowledge calls for response: to know and to do are the two sides of the coin of education.

We see that same emphasis throughout Scripture; the grand story that is being told — the proclamation of the Gospel — calls for a response. This is certainly true in Hebrews. The author has made his case for the superiority of Jesus over the whole of the Law and prophets: Jesus as the superior revelation, Jesus as the superior high priest, Jesus as the superior sacrifice. All that went before was a signpost pointing to Jesus and he is the final, superior destination toward which it pointed. And that superior telos, that superior fulfillment, calls for a superior response on the part of God’s people, a response of faith, endurance, and sacrifice. It is not enough to know; one must do. It is to that response that the author turns his attention in Hebrews 11-13.

Hebrews 11: Our Response of Faith

I do not know exactly how I managed it, but I completed many years of schooling and even became a fully functioning adult never having had a single biology course — not in high school, not in college. Now, I’m not proud of that, and, I know that it represents a significant gap in my knowledge. Perhaps for that sin God gave me a wife who worked in the medical field and later taught biology and anatomy and physiology and a daughter who majored in biology education. That means I have heard a lot of biology talk through the years. I even listened enough to learn this one thing: The mitochondrion is the powerhouse of the cell. I have very little idea of exactly what that means, but I’ve been assured by both my wife and daughter that it is true. I actually did some reading about it in preparation for this lesson. As I understand it, the mitochondrion, part of the structure of certain types of cells — certainly those cells found in humans — breaks down glucose to produce the energy rich molecule ATP which in turns powers cellular functions. The cell couldn’t do anything it does without the mitochondria providing the energy.

I wonder if there is a spiritual analog to mitochondria? Bear with my foolishness for a moment; I think this might be helpful. If we consider each one of us as a cell in the body of Christ — I know St. Paul calls us members, larger structures like hands and feet and eyes and ears, but if, for a moment, we think on the cellular level — what might be the mitochondria of that spiritual cell, the powerhouse of it that makes possible all cellular function? And, what are those essential cellular functions?

There is more than one answer that I could offer and defend as candidate for spiritual mitochondria. But, in the context of Hebrews, I think the author would answer faith. Faith is to spiritual life as mitochondria are to biological life: that without which there is no power to live and to function.

The mitochondrion is the powerhouse of the cell — a pithy, memorable description. What is faith? How might we describe it?

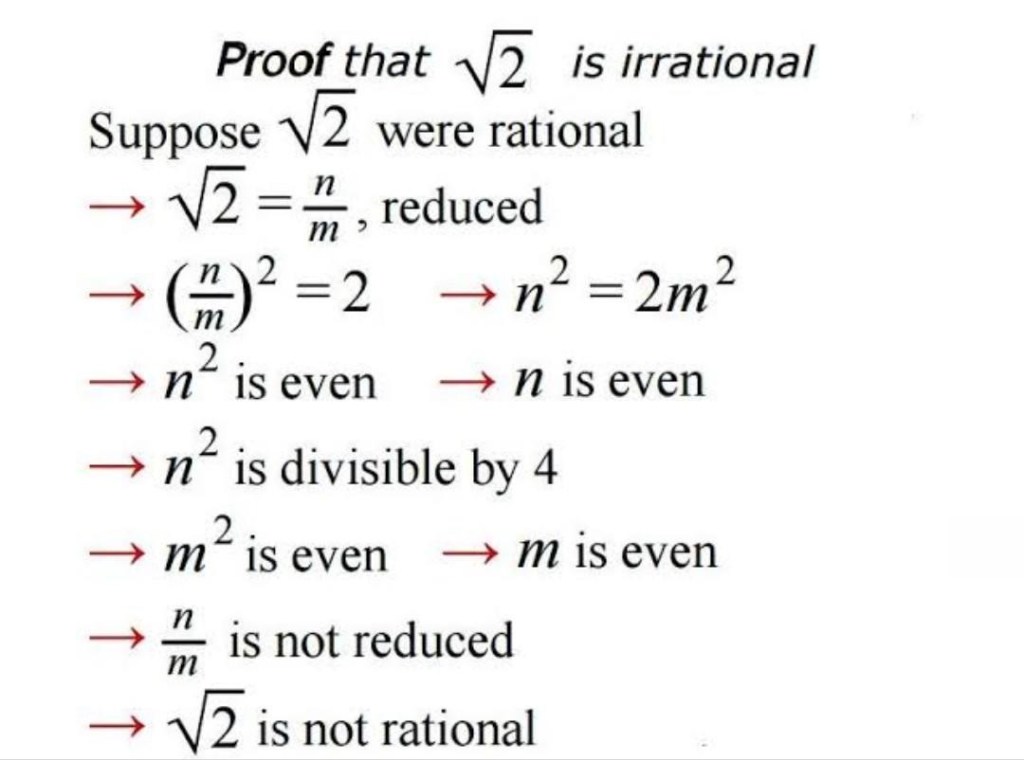

Hebrews 11:1 (ESV): 1 Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

This is not the way I first learned this verse, nor is it the way I prefer it even now. I think the King James translation captures the original language better:

Hebrews 11:1 (KJV): 1 Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

This is a weightier and more tangible wording than what we find in the ESV. The author of Hebrews has called his audience to place their hope in Jesus as the superior revelation, the superior high priest, the superior sacrifice. It is faith that gives substance to that hope, faith that constitutes the substrate, the foundation of that hope. And, faith provides the evidence, the proof of the superiority of Jesus. When we are speaking of faith in this way, it is important to do so robustly and fully. Faith is not merely a belief in something. Rather faith — living faith, as the Reformers called it — includes notitia (conceptual knowledge), assensus (agreement/assent), and fiducia (faithfulness/obedience). This kind of faith is weighty, substantial, evidentiary. This kind of faith empowers us to function as those who are committed to the superiority of Jesus, just as the mitochondria empower the cell to function biologically.

What are these spiritual functions that faith empowers? That answer comprises the remainder of Hebrews 11. I want to enumerate some of these functions according to the text and discuss just a few of them. Let’s start by filling in this blank from Hebrews 11: By faith we ________:

Understand (vs 3) — Faith is not a blind acceptance of things we do not understand but rather the means by which we understand/experience truth beyond mere reason and even beyond mere cognition. Faith is itself a way of knowing because it opens us up to relationship and experience.

Offer acceptable sacrifices (vs 4) — Think here of the widow of Zarephath who offered to Elijah, because he was the prophet of God, a portion of what would have been her final meal. Only faith could have empowered her to do that, and through her faithful sacrifice she received the blessing of life for herself and for her son. Since the sacrifices we offer to God we offer through Christ, it is faith in him that makes our sacrifices acceptable.

Please God (vs 6) — God certainly wants our love, yes, but the precursor of love is faith. There is, it seems to me, some significance to the order of things in 1 Corinthians 13: now these three remain — faith, hope, and love.

Show holy fear and become heirs of righteousness (vs 7)

Obey beyond our knowledge (vs 8) — This notion was captured well in a prayer by Trappist Monk Thomas Merton. I think it would have sounded true to Abraham, I know it sounds true to me, and I suspect it might to some of you. It is faith which powers obedience beyond our knowledge:

My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following Your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please You does in fact please You. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that, if I do this, You will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore, I will trust You always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for You are ever with me, and You will never leave me to face my perils alone. Amen.

Receive God’s promises (vs 11) — In the general absolution offered at the Eucharist the priest says, “Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who in his great mercy has promised forgiveness of sins to all those who sincerely repent and with true faith turn to him….” It is faith that makes God’s promises and blessing accessible to us. You remember when Jesus was rejected in his hometown, that he then did only a few mighty works there because of their lack of faith (Mt 13:58).

Pass testing (vss 17-18) — We are all tested: sometimes by God; sometimes by the world, the flesh, and the devil; sometimes by our own human weaknesses and passions. No one escapes testing. Faith does not help us to avoid testing, but it does help us to endure it, to find meaning in it, to walk with God through it, to pass it and to grow from it.

Bless the next generation (vs 21)

Renounce the world (vss 23-28)

Conquer (vss 29-30)

Are preserved/spared (vs 31) — I would like to extend this notion of being preserved/spared by our faith to one of the great Reformation debates: the perseverance of the saints. What confidence do we or can we have that ultimately we will be justified? I like the answer that N. T. Wright gives on this. He says, in paraphrase, that our faith is the evidence in the present moment that we shall be justified on the last great day. That threads the needle as well as any answer that I have ever seen; it allows me to come boldly before God through Jesus, our great high priest, and it cautions me to guard and nurture the faith that is in me.

The author of Hebrews says he would like to say much more about faith, but that time fails him (Heb 11:32), as it does us. But, I commend to you the remainder of the chapter, Heb 11:32-40.

Hebrews 12: Our Response of Endurance

I ran track in high school…for one week. I don’t know what madness possessed me to think I was a runner or why in the world the coach thought I should run the long distance events. But, rather than building me up to them gradually, he started me out running miles on that first day of practice. I just didn’t have the endurance for that kind of race, nor did I have much faith that I would survive long enough to develop that kind of endurance. So, I quit after a week.

My lack of endurance for track was of no real importance; it made no long term difference to either the coach or me that I quit. But, when it comes to our response to Jesus, endurance is crucial; it matters very much whether you quit or endure.

Hebrews 12:1–2 (ESV): 1 Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, 2 looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

The SEC — and certainly the Tennessee Volunteers — are known for packing football stadiums with rabid and noisy fans. The sheer number of raucous Vol-for-Life fans at Neyland Stadium does at least two things beyond filling the coffers of the UT Athletic Department: it energizes our team and it demoralizes and confuses our opponents. The Tennessee players are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses and that makes it easier for the players to lay aside fatigue, pain, self-doubt — anything that holds them back from victory — and play with endurance the game that is set before them.

Well, you see the analogy. We have a great race of faith before us — sometimes a sprint but always a marathon — and we too are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses. Who are these witnesses? In the context of Hebrews 11, the witnesses are the faithful of generations gone before, what we might call the communion of saints. I see in this word witness/μαρτύρων a double entendre: a witness is one who has seen something and one who testifies to what was seen. They were witnesses in their day to the faithfulness of God and they testified to it in the faithfulness of their lives/response. And they are still doing so, because the witness of their lives is testimony to us. And, the implication is that they are also watching us, witnessing our struggles and victories, encouraging us as fans encourage the Vols.

But, the author moves from this great cloud of witnesses to a single witness, Jesus. To whom was Jesus a witness? Again, I think there is a double meaning at work. Jesus, in enduring the cross, was a witness to the powers and principalities — both human and spiritual — that God’s love was the unconquerable power victorious over death, sin, and all the would-be powers of this fallen world. And Jesus’s endurance for the sake of the joy to come is witness to those that follow him of what it means to take up the cross and follow him, and of the suffering and glory of doing so. If we are faithful, we are and will be seated in the heavenly places with Christ Jesus (see Eph 2:6). So, in the race of faith set before us, we keep looking to Jesus as the example of faithful endurance:

Hebrews 12:3 (ESV): 3 Consider him who endured from sinners such hostility against himself, so that you may not grow weary or fainthearted.

This talk of endurance prompts some questions. First, where do all the struggles in our life of faith come from?

Our baptismal vows begin with a threefold renunciation:

Do you renounce the devil and all the spiritual forces of wickedness that rebel against God?

Do you renounce the empty promises and deadly deceits of this world that corrupt and destroy the creatures of God?

Do you renounce the sinful desires of the flesh that draw you from the love of God?

We often summarize these renunciations as a rejection of the world, the flesh, and the devil, a sort of unholy trinity. But that rejection is hard and it’s costly and it’s not one-and-done; it has to be renewed moment by moment. Take each of the renunciations in turn. What are we renouncing, and why is it difficult?

The world: How difficult is it to be out of step with the prevailing cultural expectations/norms?

The flesh: How difficult is it to curb our pleasures and to embrace sacrifice, lack, and suffering?

The devil: How difficult is it to discern and reject the lies of the devil?

So, we have these three powers ranged against us, and we are called to endure in our struggle against them. A great help in that is to see and understand this struggle as purposeful, even as a means of grace from God to us. Let me offer an analogy. In my twenties and thirties I studied and then taught karate. When a prospective student was seeking information about our school, I learned to expect two questions: What does it take to get a black belt, and how long will it take? I had a ready answer: ten dollars and about five minutes. I can sell you a black belt from our storeroom for ten dollars and we can complete the transaction in about five minutes, and then you will have a black belt if that’s what you really want. But, if you want to become a black belt practitioner of the art, then we’re talking years of hard work. You must submit yourself to the discipline of the art and endure the struggle of training day in and day out, trusting that it is for your good — not to make getting a black belt arbitrarily difficult, but so that you are transformed into a particular kind of person. Then, you can wear the belt legitimately and not as an imposter. To simply sell you a black belt would be to treat you and the discipline with disrespect.

Now, back to Hebrews. Why do we have to struggle so much against the world, the flesh, and the devil? Why such need for endurance? Because we are being submitted to a necessary discipline of transformation by God himself who loves us as sons and daughters and not as imposters (illegitimate children).

Hebrews 12:7–11 (ESV): 7 It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline? 8 If you are left without discipline, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons. 9 Besides this, we have had earthly fathers who disciplined us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? 10 For they disciplined us for a short time as it seemed best to them, but he disciplines us for our good, that we may share his holiness. 11 For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.

I think this is profoundly important for the spiritual life: to accept the struggle and suffering that come as if from the Lord, to accept it as God’s loving discipline — not as punishment, but as training — either allowed or sent because he loves us and wants us to grow into maturity as his sons and daughters. That at least provides a meaningful answer to the question of “Why?” that people struggle with in the midst of suffering and loss. Why is this happening to me/us? It is part of God’s loving discipline meant for your good and not for your destruction.

Given that understanding, how should we respond?

Hebrews 12:12–13 (ESV): 12 Therefore lift your drooping hands and strengthen your weak knees, 13 and make straight paths for your feet, so that what is lame may not be put out of joint but rather be healed.

In Man’s Search for Meaning Viktor Frankl wrote, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” To the extent we recognize and accept suffering as discipline, we have the “why.”

We do not have time to explore the remainder of this chapter, but I commend to your reading and reflection Hebrews 12:18-24; it is a glorious vision of where we stand in the New Jerusalem. I think about it often as we come together at the Eucharist.

Hebrews 13: Our Response of Sacrifice

The ESV provides a chapter heading for Hebrews 13: Sacrifices Pleasing to God. I’m a bit ambivalent about that heading; I understand it, and it makes sense on one level. But at a deeper level, I’m not so sure. Let me ask this. The pearl merchant in Jesus’s parable who sold all his other pearls to obtain the one: was that a sacrifice? Had the rich young ruler sold all his goods, given them to the poor and followed Jesus, would that have been a sacrifice? Did St. Francis who actually did renounce his former life of status, privilege, and wealth for a life of holy poverty consider that a sacrifice or a gain? Is it a sacrifice to give up a false identity based on the passing values of this world — the world, the flesh, and the devil — for a true identity as sons and daughters of God? Or is it, instead, a laudable exchange — a great and praiseworthy blessing?

The Sea/Laudable Exchange (St. Clare, adapted by John Michael Talbot)

Leave the things of earth for the things of eternity.

Choose the things of heaven o’er the goods of the earth:

To obtain the hundred fold in the place of the one,

and so possess a blessed and eternal life.

What a laudable exchange!

What a great and praiseworthy blessing!

What a laudable exchange!

Because of this I have resolved to always progress from good to better,

to be faithful in his service, to always progress from virtue to virtue:

To obtain the hundred fold in the place of the one,

and so possess a blessed and eternal life.

What a laudable exchange!

What a great and praiseworthy blessing!

What a laudable exchange!

Leave the things of earth for the things of eternity.

So, I think this chapter outlines a Christian discipline of sacrificing the ways of the world for the treasures of the kingdom of God, which, in the end, is not sacrifice at all, but a laudable exchange.

The author starts with the most fundamental discipline which is foundational to all that follows: Let brotherly love continue (Heb 13:1).

St. Thomas Aquinas defines love as “willing the good of the other,” in other words, as loving when there is no advantage to you in so doing, no good that will accrue to you. Who am I to disagree with the Angelic Doctor, as Aquinas is known? But it seems to me that there may be something beyond this or more fundamental: refusing to recognize anyone as other, realizing that God loves us all, and that there is such a thing as the common good to which we must be devoted. I don’t mean to introduce politics here, but before God my child is no more important than the child of a refugee huddled at the border. Love of the other is important, as we will see in the next verse, but it is not ultimate: brotherly love is both the foundation and the pinnacle of Christian love.

But, there are those who in this world are “others;” more accurately, there are those who are strangers to us. To them, we are to show hospitality (Heb 13:2). We think of showing hospitality to those we know, but the actual word used here — φιλοξενίας — literally means “love of stranger.” That is a challenge to us, because we live in a very different culture than that of the original audience of this epistle. Though I’ve done so, I would not want my wife to give a ride to a stranger, nor would I be likely to invite a homeless stranger to spend the night in my house. I am bound by a certain fear or caution. But I am also bound by this discipline of hospitality. So, I have to continue to struggle to see what that looks like in our cultural setting, as do you, as does the Church.

Imprisonment was a threat and reality for those to whom this letter came. In that time, prison was not punishment; it was where you waited for trial, where you waited to learn what the punishment would be. The conditions were brutal and your welfare was of no concern to the authorities. They did not supply your needs; you were dependent upon family and friends for food, clothing — all the necessities. So, the author writes almost certainly about Christian prisoners:

Hebrews 13:3 (ESV): 3 Remember those who are in prison, as though in prison with them, and those who are mistreated, since you also are in the body.

But, what about our very different cultural context? We should still remember the prisoners, as many individuals and Christian organizations do. Knox CAM (www.knowcam.org) — the Knoxville Christian Arts Ministry — presents the Gospel of Christ through music, drama, and dance in Tennessee Prisons. Men of Valor “encourages [incarcerated men] with the hope of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, welcomes them into the family of God, trains them in the Biblical principles of manhood, and with a very structured plan, helps them to become the men, husbands, fathers, and members of society that God created them to be” (www.men-of-valor.org). There are ways in which we can still remember those in prison and support those who are already doing so.

Another part of our discipline is sexual purity:

Hebrews 13:4 (ESV): 4 Let marriage be held in honor among all, and let the marriage bed be undefiled, for God will judge the sexually immoral and adulterous.

Our culture tells us that sex is a private matter, no one’s business but our own, and that casual, recreational sex — emotionally and spiritually meaningless sex — is quite harmless and even beneficial. It’s a lie. Marriage and the marital sexual relationship is an icon of Christ and the Church, an icon of utter self-sacrificing commitment. All sexual relations create a bond between partners: more is joined than bodies, and that has profound emotional, psychological, and spiritual implications. We live in a culture addicted to “casual, meaningless sex” and broken by that addiction. We have a better way, a discipline that promotes wholeness and integrity.

Then the author cautions us once again about greed — Hebrews 13:5 (ESV): 5 Keep your life free from love of money, and be content with what you have, for he has said, “I will never leave you nor forsake you.” — but I’ll pass over that since we have discussed it in some detail earlier.

Finally, the author moves to the inner dynamics of the Christian community:

Hebrews 13:7, 17 (ESV): 7 Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God. Consider the outcome of their way of life, and imitate their faith.

17 Obey your leaders and submit to them, for they are keeping watch over your souls, as those who will have to give an account. Let them do this with joy and not with groaning, for that would be of no advantage to you.

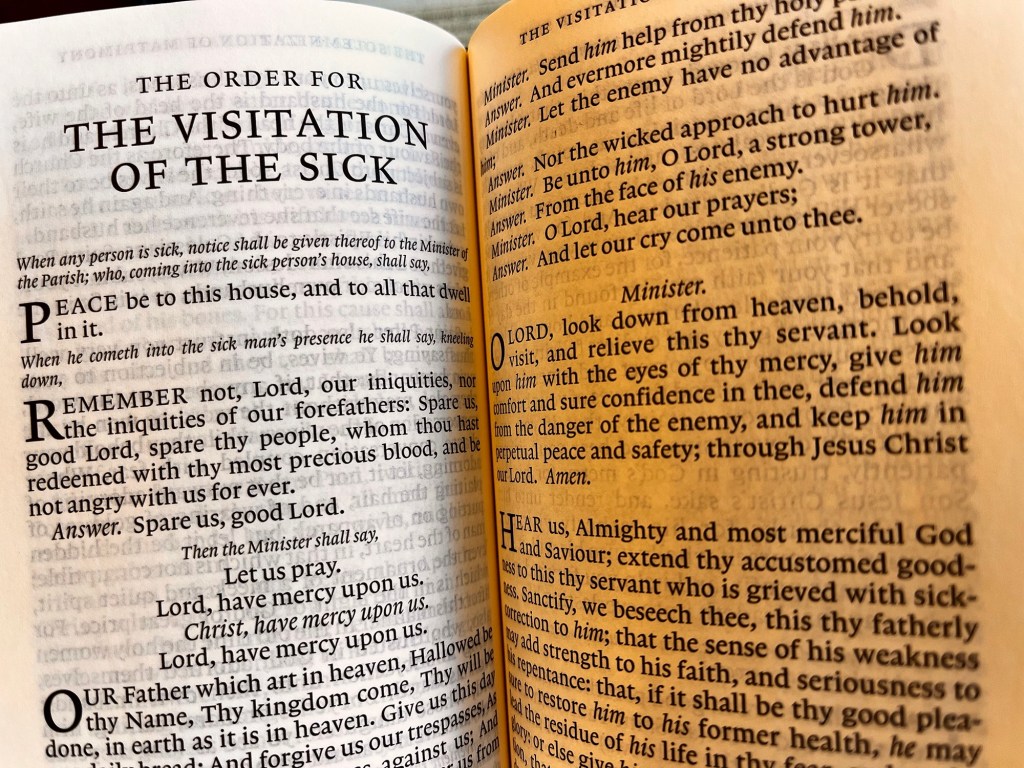

When a deacon or priest is ordained in our diocese, that ordinand must take an Oath of Canonical Obedience — both orally and in writing:

…I do promise, here in the presence of Almighty God and of the Church, that I will pay true and canonical obedience in all things lawful and honest to the Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of the South, and his successor, so help me God (BCP 2019, p. 485).

Now, most Christians are not ordained to vocational ministry, but the author still calls them to obedience to their spiritual leaders: not to abusive spiritual leaders or to manipulative ones, but to those way of life models that of Christ, whose faith is worth imitating, and who are caring for the souls of those for whom they have spiritual responsibility.

Conclusion

This must conclude our overview of the Epistle to the Hebrews in which we have considered the superiority of Christ: the superior revelation, the superior high priest, the superior sacrifice, and our superior response. I hope it has stirred in you a desire to explore this letter in more detail. It seems fitting to close with the final benediction of the letter itself:

Hebrews 13:20–21 (ESV): 20 Now may the God of peace who brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, the great shepherd of the sheep, by the blood of the eternal covenant, 21 equip you with everything good that you may do his will, working in us that which is pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ, to whom be glory forever and ever.

And the blessing of God Almighty — the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit — be among you and remain with you always. Amen.