Session 2: The Holy Spirit in the Creeds

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

The Theology of the Holy Spirit

Session 2: The Holy Spirit in the Creeds

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

O God the Father, Creator of heaven and earth,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Son, Redeemer of the world,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Holy Spirit, Sanctifier of the faithful,

Have mercy upon us.

O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, one God,

Have mercy upon us (The Great Litany, BCP 2019, p. 91).

Introduction: What Is It Like to Be a Bat?

In 1974, an American philosopher Thomas Nagel published a paper in The Philosophical Review whose title was this question: “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” It is probably one of the most important and influential philosophical papers published in the last half century or so. It is — to the extent I understand it — a consideration of the limits of human knowledge and perspective. Let me try to explain the basic notion, the “big picture,” of the paper.

There are many things we can say about bats just through observation. Bats navigate the world primarily by echo-location instead of by sight, as humans do. Bats fly where humans walk or ride in vehicles. Bats eat insects and most humans try not to. Bats hang upside down on branches or cave walls to sleep, while humans sleep prone on Sleep Number mattresses. More could be said about bat physiology and behavior, but what we know comes by observation and study. And none of that observation and study tells us in the least what it is like to be a bat, to engage with and to perceive the world as a bat does. There is a fundamental and inescapable difference between a bat’s perspective of itself and the world and a human’s perspective of batness. Even if we attempt to understand or imagine what it is like to be a bat, we are, at best, imagining what it would be like to have our human understanding and perception in a bat’s body, simply because it is our brain trying to understand or imagine being a bat. When we ask for example, “What would it be like to fly?” we are really asking what it would be like for us as humans to fly in a bat’s body, not what it must be like for a bat to fly in its own body. We simply cannot bridge those limits of understanding, perception, and perspective. We cannot know what it is like to be a bat.

We bump up hard against those same limitations when we speak of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. We can know and say some things by observation and study. We can know and say more by revelation, by God making himself known. But, there are inherent limits to our knowledge, perception, and perspective. We cannot know what it is like to be God. So, we can and will and must say some things — hold as true some doctrines — that are beyond the limits of our understanding. That is not — it should not be — a cause of embarrassment; it is simply a humble recognition of the inherent limits of human knowledge. God is in a way that we are not, and we cannot perceive what it is like to be God. We can use analogies and metaphors, but all of them ultimately break down if pushed too far. Even the best are false in the sense of being partial: God from our perspective and not from God’s own perspective.

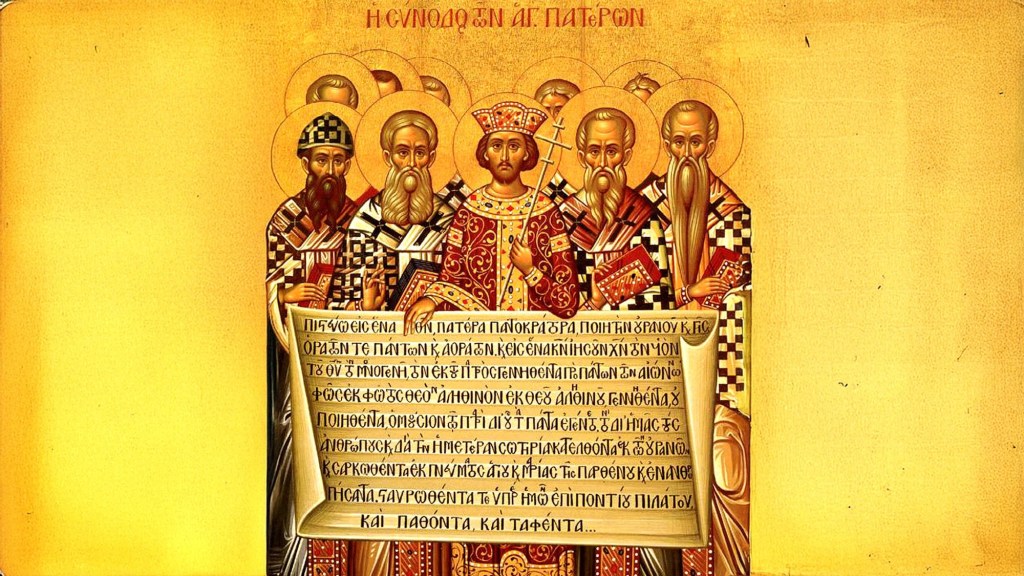

Remember the process of spiritual knowledge that we discussed last week: experience, dissonance, Scripture and the life and worship of the Church. This week, I would add to that creeds, councils, and catechisms. We experience something of the Holy Spirit. If it is a new experience for the Church or for us, as we often see in the pages of Scripture, we experience a certain cognitive and spiritual dissonance. To resolve that dissonance, to figure out what the experience means, we search the Scriptures in communion with the Church and in participation with its life and worship. Our fathers in the faith followed that same process and then expressed their “findings” in creeds and councils and catechisms. These tell us the truth about God and protect us from error in thinking and speaking of God, but they, too, pretty quickly reach the limits of human understanding. So, we will say not infrequently: this concept is true; we know it by revelation, by experience/observation, through the faith and practice of the Church and her saints, but we do not understand it fully. We do not know what it is like to be a bat, nor do we know what it is like to be God. Creeds, councils, and catechisms are essential, are vital in protecting us from error, but they cannot fully bridge the limits of our understanding. As N. T. Wright might describe them, they are signposts pointing toward the truth. And the truth sometimes lies far down a fog covered road.

Even given the limits of human understanding, and precisely because of the limits of human understanding, we receive and treasure these creeds as truth experienced and truth revealed, as truth verified by Scripture and expressed by the Church. We say it this way in the Fundamental Declarations of the Province (ACNA):

We confess as proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture the historic faith of the undivided church as declared in the three Catholic Creeds: the Apostles’, the Nicene, and the Athanasian (BCP 2019, p. 767).

It is now to these creeds we turn in our engagement with the Holy Spirit.

The Apostles and Nicene Creeds

The Apostles Creed in the Daily Office and the Nicene Creed in the service of Holy Eucharist are the two creeds that we use in worship most frequently. Drawing from Scripture — prominently from the Gospels of Sts. Matthew and Luke — both of these creeds emphasize the agency of the Holy Spirit in the incarnation of our Lord.

Apostles Creed

I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord.

He was conceived by the Holy Spirit

and born of the Virgin Mary.

Nicene Creed

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only-begotten Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven,

was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary,and was made man.

There is much to unpack there, particularly in the Nicene Creed. Let’s start with this question: Why is the agency of the Holy Spirit in the incarnation of Jesus Christ crucial to the Church’s understanding of the Holy Spirit?

The vital principle at work here is simply this: like begets like. Here is how St. James puts it in a series of rhetorical questions:

11 Does a spring pour forth from the same opening both fresh and salt water? 12 Can a fig tree, my brothers, bear olives, or a grapevine produce figs? Neither can a salt pond yield fresh water (James 3:11-12).

An olive tree produces olives and a fig tree produces figs; like begets like. Very early — it’s clearly present in the Gospels and in the Epistles — the Church concluded that the man Jesus was also God, though defining clearly what that means was a few centuries in coming. The Creeds insist on it: Jesus, the only-begotten Son of God, the eternally begotten, God from God. Here, when speaking of the eternally begotten Son, we are speaking of the Logos/Word, the Second Person of the Trinity. But what of Jesus of Nazareth, God incarnate, both fully God and fully man? The Holy Spirit was the agent of incarnation. The Holy Spirit was instrumental in the union of God and man in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary. But this is surely beyond the power of any man to accomplish. What then is the conclusion we must draw? Simply that the Holy Spirit must also be God, though in a way not yet specified. So, in the incarnation, we have the Trinity foreshadowed: the Father eternally begets the Son, the Son takes to himself a human nature, and the Holy Spirit is the agent of that incarnation. This is a principle that we will see throughout Scripture and the thinking of the Fathers: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit act together. More about this later.

The Holy Spirit appears again in both Creeds.

Apostles Creed

I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and the life everlasting. Amen.

This seems to be like the kitchen drawer we all have. You know the one — the odds-and-ends drawer that has everything in it that we don’t know what else to do with. It seems like a lot of theological whatnots crammed into this “stanza” of the creed willy nilly. But, there may be more order to this than we first see. Notice that both the Apostles Creed and the Nicene Creed have three sections or stanzas: one for God the Father, one for God the Son, and one for God the Holy Spirit. So all this apparent hodgepodge might not be that at all. Let’s turn to the Nicene Creed, in its section about the Holy Spirit.

Nicene Creed

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father [and the Son],

who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one Baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

There is more here than in the Apostles Creed, but there are some common features between them: the Church, forgiveness of sins, resurrection, everlasting life (life of the world to come). So, what does this overlap in the Creeds in the section on the Holy Spirit tell us? At least this: that the Holy Spirit is God present and active in the Church, in forgiveness of sins (not least in Baptism), in the resurrection to come, and in eternal life. We see this expanded, fleshed out, in the faith and practice of the Church, not least in the Sacraments which we will examine in a subsequent lesson. But, just from this we can see that the Holy Spirit is integral to the entire life of faith, from our new birth in baptism, to the life and ministry of the Church, to the coming resurrection and life in the kingdom. The Nicene Creed also mentions the Holy Spirit speaking through the prophets, that is, the role of the Holy Spirit in the inspiration of Scripture. The Holy Spirit suffuses, empowers, makes possible every aspect of Christian life.

The Athanasian Creed

Now, let’s turn our attention to a less well known and less used Creed, the Athanasian Creed, the one we recite on Trinity Sunday. This is strictly a creed of the Western Church; it does not enter into the faith and practice of the Eastern Church, the Orthodox Churches. It is longer than the other creeds, seemingly repetitious/redundant — though it really isn’t — and challenging. But, it will well repay the time spent with it. We will limit our reflection on it to the first section of the Creed which deals with the nature of the Trinity. The second section is devoted to Christology, the nature of Christ.

The Creed opens with an essential distinction between Substance and Person.

Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary

that he hold the Catholic Faith.

Which Faith except everyone do keep whole and undefiled,

without doubt he shall perish everlastingly.

And the Catholic Faith is this:

That we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity,

neither confounding the Persons, nor dividing the Substance.

For there is one Person of the Father, another of the Son,

and another of the Holy Ghost.

But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son,

and of the Holy Ghost, is all one,

the Glory equal, the Majesty co-eternal.

Such as the Father is, such is the Son,

and such is the Holy Ghost.

Do you remember the philosophical paper we started our discussion with: “What Is It Like to Be a Bat”? The essence of the paper is that it is impossible for humans to bridge their inherent limits of understanding, perception, and perspective and therefore it is impossible to know what it is like to be a bat. We can know things about bats, study and describe bat behavior, but we can never know or experience these things from a bat’s perspective. How much more is that true of the Trinity! We cannot know from God’s perspective what it means to be both Trinity and Unity. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t and can’t say some true things about the nature of God — in fact we must in order to define the orthodox faith and to avoid error — but it does mean that everything we think and say is limited by our human understanding, perspective, language, and images. So, we say about the Creed, this is what we believe/know to be true based on Scripture, revelation, reason, the life and worship of the Church — what we believe/know to be true even though we cannot fully understand, perceive, or explain how it is so.

We start with the most fundamental notion of all, the most fundamental revelation of God to Israel: Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one. There are other spiritual, other heavenly beings that Scripture refers to as gods and sons of God, but they are created beings, created by this Most High God spoken of in the Creed. They do not share in the fullness of his being as the Creed will reveal it.

This one God exists in triune form: one God — that is, one Substance — in three Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit; the Creed says Holy Ghost, but I will continue to use Holy Spirit. This — the distinction between Substance and Person — is where things get dicey, and I will have to resort to images that fail if pushed too far. I think they are helpful, but they are limited; remember the bat.

Let’s try to distinguish between Substance and Person. I am going to imagine something that we cannot do, that certainly cannot be done, though the Creed also takes a stab at it. Imagine taking a sheet of paper and writing down all the essential characteristics of God, everything that makes God God. We can get a sense of this by scanning the Creed; here are some divine characteristics that it mentions:

Uncreated: everything other than God was created by God, but God himself is the First Cause, the Unmoved Mover, uncreated by anything else. Do you remember the name by which God revealed himself to Moses? I Am: all being resides in him. God is not one created being among other; he is the uncreated source of all being. God does not, in that sense, even exist as we exist. He is self-existent and we are not. We are contingent; we might not have been. But God is not contingent; God could not not be. To be God is to be.

Incomprehensible: he is far beyond the limits of our understanding, beyond our power to grasp and encompass.

Eternal: God is self-sufficiently without beginning and without end. We had a beginning, at conception; God did not. We do not have an eternal future in ourselves; it is granted only by God.

So, we have these three characteristics of God enumerated in the Creed: uncreated, incomprehensible, eternal. Imagine that it is possible to continue this list to include all the defining characteristics of God. We might title this list “God’s Nature” or “God’s Substance.” Only God has all these characteristics, and anyone who has them all is God. What we find — by revelation — is that there is only One. And yet, within that One — constitutive of that One — there is a distinction of Persons, three in number identified as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each has the Substance of God; it is not divvied up among the three. Each is uncreated, incomprehensible, eternal, glorious, majestic. Each is Lord. There is only one God. But, there are three Persons; there is distinction in the unity: not three Gods, but three Persons in the Unity of the Godhead.

So, where does the distinction lie? The Person of the Son — not the humanity of Jesus, but the Person of the eternal Son/Word/Logos — is begotten of the Person of the Father, but the Father is not begotten. The Person of the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father — not begotten like the Son, but proceeding — but the Father is not proceeding. All of this is to say that there is a distinction among Persons, but no distinction in Substance. To ask what that means is to ask what it’s like to be a bat. The best we can do is to echo the Creed. The Persons of the Trinity are not interchangeable; they are not identical. But, they are one in Substance and indivisible — equal in glory and honor and worship. Here is how the Creed says it:

So are we forbidden by the Catholic Religion, to say,

There be three Gods, or three Lords.

The Father is made of none, neither created, nor begotten.

The Son is of the Father alone, not made, nor created,

but begotten.

The Holy Ghost is of the Father and of the Son,

neither made, nor created, nor begotten, but proceeding.

So there is one Father, not three Fathers;

one Son, not three Sons;

one Holy Ghost, not three Holy Ghosts.

And in this Trinity none is afore, or after other;

none is greater, or less than another;

But the whole three Persons are co-eternal together

and co-equal.

So that in all things, as is aforesaid, the Unity in Trinity

and the Trinity in Unity is to be worshiped.

He therefore that will be saved must thus think of the Trinity.

Why is this so important to our discussion of the Holy Spirit? Remember the process we discussed in the first lesson: experience, dissonance, Scripture, the faith and worship of the Church. This understanding of the Trinity did not happen instantaneously. It took the Church generations to go through this process and to be able to articulate its faith in creeds and councils and catechisms and liturgies. The acceptance of the Holy Spirit as God was the last brick to be put in place. It is all there in Scripture, but learning to read the Scripture rightly, to see what was there all along, was a process, a process aided by the Holy Spirit himself.

The implications of this understanding are vast. When we are born of water and Spirit in baptism, it is God himself, in the Person of the Holy Spirit, who births us; we become children of God. When the Holy Spirit indwells us, it is God himself, in the Person of the Holy Spirit, who unites himself to us. When we take up the Scripture breathed out by the Spirit, it is God’s own word and it is God himself, in the Person of the Holy Spirit, who helps us discern the truth in it.

The unity with distinction of the Trinity is also a paradigm for the Church. There is only one Church, so we believe and so we say each day or week in the Creeds: one holy catholic and Apostolic Church. That is true because there is one Lord, one faith, one Baptism — one Holy Spirit who unites us. We might — echoing the language of the Athanasian Creed — say that the Church is one in substance. But, there is distinction and even diversity in that unity; there are many persons in the Church. The Church is comprised of people from every family, language, people and nation. The Spirit draws all these people together, makes them one without erasing their differences, and gives a variety of gifts. Here is how St. Paul describes it in 1 Corinthians:

4 Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; 5 and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; 6 and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who empowers them all in everyone. 7 To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good. 8 For to one is given through the Spirit the utterance of wisdom, and to another the utterance of knowledge according to the same Spirit, 9 to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by the one Spirit, 10 to another the working of miracles, to another prophecy, to another the ability to distinguish between spirits, to another various kinds of tongues, to another the interpretation of tongues. 11 All these are empowered by one and the same Spirit, who apportions to each one individually as he wills.

12 For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. 13 For in one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit.

14 For the body does not consist of one member but of many (1 Cor 12:4-14).

So, the unity with distinction of the Church is a signpost pointing to the very nature of the Trinity, a signpost made possible by the unifying power of the Holy Spirit in the Church and the gifting of individual Christians for the good of the Church.

The whole notion of personhood — one God in three Persons — has important implications for us, as well. As I have presented it in this lesson, following the approach of the Athanasian Creed, I have based personhood on distinctives. The Son is a Person by virtue of being begotten of the Father; the Holy Spirit is a Person by virtue of proceeding from the Father; the Father is a Person by virtue of being neither begotten not proceeding. It was necessary for the Creed’s purposes to present personhood in this way. But there is something other than differences that is just as fundamental to personhood: relationships.

Let me explain using a personal example. I had just turned twenty when Clare and I were married. This September we will celebrate our 48th anniversary. I am the person that I am in large part due to that relationship. I barely know where I start and leave off and where Clare does. I don’t think in terms of John any longer, but rather in terms of John and Clare. Had we never met and never married, had I married someone else or joined a monastery, I would be a different person today. My personhood is dependent upon that relationship, but not on that one only. I was born into a particular family, had a certain circle of friends, was raised in a particular church, and now I am here in relationship with you. All of these relationships are an essential part of my personhood. My point is this: personhood, in the fullest sense, is contingent upon relationship. So, when we are talking about God in three Persons, we are necessarily talking about God in relationship; relationship is part of the nature of God. If God were a monad — a single, undifferentiated entity — from all eternity, God would not be a Person. But our God is a God in relationship with himself and with us.

Human relationships can be healthy or unhealthy, transactional or self-giving, parasitic or mutually beneficial. What about the relationship between God and man? There are many images from Scripture that we can use to illustrate it, but I like the one that Bp. Robert Barron uses frequently: the burning bush. Moses had almost certainly seen bushes on fire before, if only in the fires he kindled on those long nights tending the sheep. But this one was different. What was so intriguing to Moses about this burning bush? It was not consumed. When God in-dwelt the bush, he did not diminish or destroy it; God occupied the same space without competition. Instead, God’s relationship with the bushed enhanced the bush, glorified it, transfigured it while leaving it fully itself. In fact, it made the bush more itself than it ever was before. That is the essence of our relationship with God. When the Holy Spirit indwells a Christian, that relationship is not competitive. More of the Holy Spirit does not mean less of the person. Rather, the Holy Spirit enhances the person, transforms the person, transfigures the person while making that person more truly and fully himself/herself. Our true personhood lies in relationship with our God in three Persons, mediated especially through the Holy Spirit.

This has important implications for the Church. If our full personhood is contingent on relationships, then we need one another in the Church; we become persons together. But, I want to suggest that the trinitarian model — three persons in relationship — is a necessary paradigm for all Christian relationships: never just two, but always three. The third in every Christian relationship is always Christ. Dietrich Bonhoeffer explored this triune Christian relationship most profoundly in his book Life Together:

Because Christ stands between me and others, I dare not desire direct fellowship with them. As only Christ can speak to me in such a way that I may be saved, so others, too, can be saved only by Christ himself. This means that I must release the other person from every attempt of mine to regulate, coerce, and dominate him with my love. The other person needs to retain his independence of me; to be loved for what he is, as one for whom Christ became man, died, and rose again, for whom Christ bought forgiveness of sins and eternal life. Because Christ has long since acted decisively from my brother, before I could begin to act, I must leave him his freedom to be Christ’s; I must meet him only as the person that he already is in Christ’s eyes. This is the meaning of the proposition that we can meet others only through the mediation of Christ (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together, HarperCollins (1993), pp. 26-27).

Bonhoeffer speaks about Christ standing between me and the other. But, I would suggest that it is the Holy Spirit who mediates between us, because it is the Holy Spirit who indwells each of us and who unites us one with another in Christ. I wouldn’t want to argue that point; what is essential is that all Christian relations be triune in form and nature. So, the Trinity once again becomes the paradigm for our life together.

Conclusion

There is much more to be gleaned from the Creeds, but we have made a good beginning regarding the Holy Spirit. And what have we found?

The Holy Spirit is God in all respects. He — not It — is consubstantial with, of the same Substance as, both the Father and the Son. That is, there are no essential characteristics of the divine nature that the Holy Spirit lacks. Therefore, he is worthy of equal praise, honor, and majesty as the Father and the Son: as to the Father and to the Son, so to the Holy Spirit.

Yet, though of the same Substance, the Holy Spirit is not identical to either the Father or the Son; he is his own distinct Person as are the Father and the Son. He is a distinct Person in his procession from the Father [and from the Son], and in the unique relationship he has with both the Father and the Son. The Holy Spirit’s role is unique in creation, redemption, and restoration. For example, the Holy Spirit did not die for our sins; the incarnate Son of God accomplished that. But, the Holy Spirit was the divine agent of the incarnation who made possible our redemption through Jesus Christ. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one in purpose but distinct in activity.

The Holy Spirit is God present with, in, and through the Church: in our birth in baptism, in our strengthening in the Eucharist, in our healing through confession, in our gifting for ministry, in our unity in relationship (the communion of saints). The self-giving mutuality of the Holy Trinity is the paradigm for our life in the Church.

We do not know what it is like to be a bat; nor do we know what it is like to be God. But we do know from experience, from Scripture, from the faith and practice of the Church, and from the Creeds that the Holy Spirit is essential to our individual lives and to the life of the Church.

I close with an Orthodox prayer to the Holy Spirit.

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

O Heavenly King, Comforter, Spirit of Truth who art everywhere present and fillest all things, Treasury of Good Things and Giver of Life: come and dwell in us and cleanse us of all impurity, and save our souls, O Good One. Amen.