Session 5: Fruit and Gifts of the Spirit

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

The Theology of the Holy Spirit

Session 5: Fruit and Gifts of the Spirit

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

O God the Father, Creator of heaven and earth,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Son, Redeemer of the world,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Holy Spirit, Sanctifier of the faithful,

Have mercy upon us.

O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, one God,

Have mercy upon us (The Great Litany, BCP 2019, p. 91).

Introduction: Identity

Identity has been on my mind lately as I have helped my daughter navigate her post-wedding name change through the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). That process has raised all kinds of questions like: (1) Why are governmental agencies — at both the county and federal levels — so unresponsive to citizens’ questions and needs? and, more philosophically, (2) What is the nature of the relationship between one’s name and one’s identity?

Anyway, identity has been on my mind lately. And that has raised a theological question that actually is important, not least for our understanding of the Holy Spirit: What is the most fundamental identity of a Christian? Asked in other words: How does God the Father see us — most fundamentally? Note that the last question is akin to these: (1) Who is buried in Lincoln’s tomb? and (2) What color black horse did Alexander the Great ride? The answer is explicit in the question. If we are to call and consider God “our Father” then we are, by definition, God’s children.

Let’s confirm this logic with Scripture, as we always should do.

3 Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places, 4 even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before him. In love 5 he predestined us for adoption to himself as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will, 6 to the praise of his glorious grace, with which he has blessed us in the Beloved (Eph 1:3-6).

4 But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, 5 to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. 6 And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” 7 So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God (Gal 4:4-7).

So, based on these Scriptures — and there are others like them — what is our most fundamental identity as Christians? We are adopted sons of God. I don’t want to make too much of the gendered nature of these texts — adopted sons — in part because Roman laws of adoption were complex beyond my level of interest. But, it seems to be generally true that sons had certain rights (and obligations) that daughters did not have. To be adopted as sons — even as female “sons” — is to receive the full benefits of the familial relationship. It is also true that other texts — we will look at one in 1 John in a moment — say that we are children of God, not specifically sons.

But, I am very interested in this notion of adoption. What I say next is not to diminish adoption in any sense — God forbid! — but simply to identify it for what it is. Adoption is a civic action that creates a legal relationship in lieu of a biological relationship. We place great emotional significance on adoption, as is appropriate. The Romans did not. For them it was more a matter of succession and inheritance than of emotional relationship. Adoption conferred rights and responsibilities. Adoption changed the legal status of the one adopted, but not the fundamental nature of that person.

Now, bear with me as we push this a little further; it is important that we do so. I’ve made the claim that, in ancient Rome, adoption affected a change in legal status, but not (necessarily) a change in nature. But, the picture is more complex than that. Imagine a son — it could equally well be a daughter — adopted as pre-adolescent. By that age certain patterns of behavior will have been formed; a certain self-understood identify will have been fashioned. Now, place that pre-adolescent in a new family with very different patterns and identity. He is legally a son, but not yet a son in terms of nature. That will grow over time as he forms new relationships, learns and adopts new values and behaviors, and comes to represent, in himself, what his new family represents. He has become, by the grace of adoption, what the family is by nature. He demonstrates all the characteristics of the family, and he is, in every sense but biology, a true son. Or, he may refuse his full sonship by holding onto his pre-adoption values and behaviors. This change in nature isn’t automatic; it must be accepted, pursued, and developed.

Fruit of the Spirit

Now, let’s begin to relate all this to the Holy Spirit. It is in baptism that we are adopted as sons of God. And we have seen previously that the Holy Spirit is the divine agent of that baptismal identity. Galatians 4:6 emphasizes that again: it is the presence of the Holy Spirit in our hearts that allows us to cry to God, “Abba! Father!” Now, here is the question — the essential question: Is that adoption merely a civic action — a legal matter, so to speak — or does it accomplish, in some sense yet to be defined, a change in nature?

The answer isn’t either/or but both/and. In baptism we are transferred from one kingdom to another: freed from the dominion of Satan and made citizens of heaven. Likewise we are released from slavery to sin; its power over us is broken. There is some juridical — some quasi-legal — language and imagery there. But, at the same time, we are born again of water and Spirit. By God’s grace and through the agency of the Holy Spirit, there is a change in — really, a renewal of — nature, at least the beginning of a change and renewal. Now, it is up to us to grow into the fullness of that renewed nature, to take on the values and behaviors of a true son in our new family, the family of God.

Now, let me switch images. Suppose it is wintertime and, while walking, we happen upon a grove of fruit trees. Not being either botanists or farmers, we might well not recognize, simply from the bark or the shape of the tree, what kind of tree it is.

How could we ever tell, definitively, the species of tree? Well, it will require a bit of patience, but we could come back when the tree is bearing fruit; that would tell us its true identity, its true nature. The proof of the nature is in the fruit.

You probably see where I am going with this. The proof of one’s nature — whether fallen or renewed — is in the fruit of one’s life, either fruit of the flesh or fruit of the Spirit. If we wish to move from merely the status of sonship to the fullness of it, we must move from the fruit of the flesh — or from a general barrenness — to the fruit of the Spirit.

16 But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh. 17 For the desires of the flesh are against the Spirit, and the desires of the Spirit are against the flesh, for these are opposed to each other, to keep you from doing the things you want to do. 18 But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not under the law. 19 Now the works of the flesh are evident: sexual immorality, impurity, sensuality, 20 idolatry, sorcery, enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, divisions, 21 envy, drunkenness, orgies, and things like these. I warn you, as I warned you before, that those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom of God. 22 But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, 23 gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law. 24 And those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires.

25 If we live by the Spirit, let us also keep in step with the Spirit. (Gal 5:16-25).

Now, I need to slightly nuance what a said earlier. I said that the proof of one’s nature — whether fallen or renewed — is in the fruit of one’s life, either fruit of the flesh or fruit of the Spirit. More precisely, I should say that the presence of the desires of the flesh and the absence of the fruit of the Spirit, is pretty compelling evidence that one has not moved on from the status of sonship to the reality and fullness of it. This is not a call to begin judging those around us — God forbid! But it is a call for self-examination, and for attention to those areas where we are not as fruitful as we should be.

Love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control: are these the words that people use to describe us collectively and individually? Which ones on the list might they leave out in the description? This character, these traits: this is what it means for the Holy Spirit to move us from the mere status of sons to the true nature of sons. Jesus gives this character as a goal for us, and as a defining feature of our identity:

43 “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ 44 But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, 45 so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven. For he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust (Matt 5:43-45).

Jesus focuses on love as the prime virtue. But all the rest — joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control — flow from that love. They are all made possible by the Holy Spirit. They are made real by our cooperation — our participation — with the Holy Spirit. We are fellow-workers with the Holy Spirit in the cultivation of the virtues of sonship. We have to desire these virtues, seek them not least through prayer, practice them at every opportunity, repent when we fail to do, and start again.

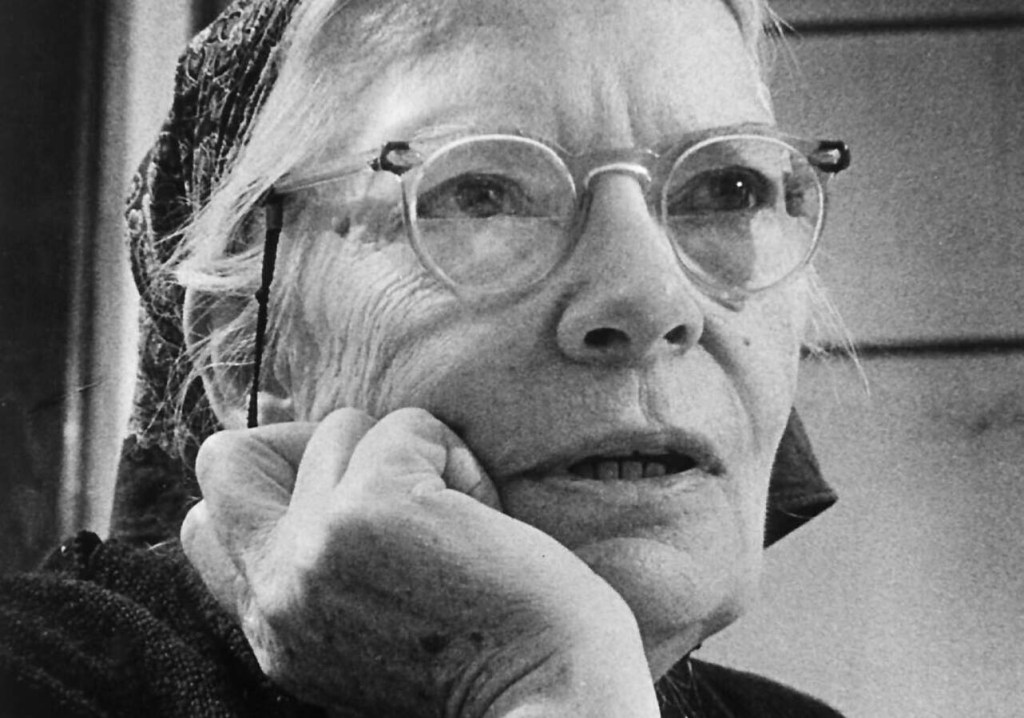

Roman Catholic social advocate Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, said that Christians should make decisions, should take actions, based on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy which reflect and make tangible the fruit of the Spirit:

Corporal Works of Mercy

To feed the hungry;

To give drink to the thirsty;

To clothe the naked;

To shelter the homeless;

To visit the sick;

To free the captive;

To bury the dead.

Spiritual Works of Mercy

To instruct the ignorant;

To counsel the doubtful;

To admonish sinners;

To bear wrongs patiently;

To forgive offenses willingly;

To comfort the afflicted;

To pray for the living and the dead.

These are wonderful practices for us, particularly as a rule of life for our behavior. But, we could also use the fruit of the Spirit in a similar way. Simply ask, “Does the course of action I am considering demonstrate and nurture love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control?” If not, then it is not the way of the Spirit. We could simply ask ourselves: In this moment how should I act to show love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control? Then, do that.

I close this section on the fruit of the Spirit with words from St. Peter and from St. John. Remember that our goal — God’s purpose for us — is to move from the status of sonship to the divine nature of sonship. That is exactly what St. Peter emphasizes in his second letter:

3 His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, 4 by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped from the corruption that is in the world because of sinful desire. 5 For this very reason, make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue, and virtue with knowledge, 6 and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with steadfastness, and steadfastness with godliness, 7 and godliness with brotherly affection, and brotherly affection with love. 8 For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they keep you from being ineffective or unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For whoever lacks these qualities is so nearsighted that he is blind, having forgotten that he was cleansed from his former sins. 10 Therefore, brothers, be all the more diligent to confirm your calling and election, for if you practice these qualities you will never fall. 11 For in this way there will be richly provided for you an entrance into the eternal kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ (2 Peter 1:3-11).

St. Peter says that these qualities he enumerates — and you see great overlap in his list and St. Paul’s fruit of the Spirit — if they are ours and they are increasing, confirm our calling and our election. In the language we have been using, these qualities take us beyond the status of sonship to the reality of the divine nature of sonship.

St. John writes similarly about moving from status to nature, but with an even broader outlook, an outlook that keeps in mind the end of all things:

28 And now, little children, abide in him, so that when he appears we may have confidence and not shrink from him in shame at his coming. 29 If you know that he is righteous, you may be sure that everyone who practices righteousness has been born of him.

3 See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are. The reason why the world does not know us is that it did not know him. 2 Beloved, we are God’s children now, and what we will be has not yet appeared; but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is. 3 And everyone who thus hopes in him purifies himself as he is pure (1 John 2:28-3:3).

We are sons now, and as we abide in him and practice righteousness we may be certain of that, and I think it is fair to say that we will grow more deeply into our sonship. But there is something greater out there for us in the future, at Christ’s appearing: the fullness of our sonship that we cannot now even begin to imagine. And because we hope for that — and here “hope” means the absolute assurance of something that we know to be coming — we purify ourselves now. We cooperate with the Holy Spirit in deepening the nature of our sonship. We cultivate the fruit of the Spirit.

Gifts of the Spirit

Having looked at the fruit of the Spirit, now we turn out attention to the gifts of the Spirit. While there are several catalogs of these gifts in Scripture — not identical, but with significant agreement — we will focus primarily on St. Paul’s discussion of them in 1 Corinthians. I do this, in part, because the Corinthian church(es) were struggling to come to grips with these spiritual gifts, and St, Paul goes into quite a bit of detail to help them manage these manifestations of the Spirit. The whole of 1 Corinthians 12-14 is essential for an understanding of the spiritual gifts. We begin with 1 Cor 12:1-11.

12 Now concerning spiritual gifts, brothers, I do not want you to be uninformed. 2 You know that when you were pagans you were led astray to mute idols, however you were led. 3 Therefore I want you to understand that no one speaking in the Spirit of God ever says “Jesus is accursed!” and no one can say “Jesus is Lord” except in the Holy Spirit.

4 Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; 5 and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; 6 and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who empowers them all in everyone. 7 To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good. 8 For to one is given through the Spirit the utterance of wisdom, and to another the utterance of knowledge according to the same Spirit, 9 to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by the one Spirit, 10 to another the working of miracles, to another prophecy, to another the ability to distinguish between spirits, to another various kinds of tongues, to another the interpretation of tongues. 11 All these are empowered by one and the same Spirit, who apportions to each one individually as he wills (1 Cor 12:1-11).

First, notice that there were a variety of spiritual gifts operative in the church: wisdom, knowledge, faith, healing, miracles, prophecy, discernment of spirits, tongues, and interpretation of tongues. This list is probably typical but not exhaustive of the first century spiritual gifts. All of these, in their great diversity, are from the same source and directed toward the same purpose.

What is the source of the spiritual gifts? The same Spirit, the same Lord, the one Spirit, one and the same Spirit: though there is a diversity of gifts, there is a unity of source. These gifts come from the Spirit and are not simply natural abilities, though they may be natural abilities perfected — raised to a new level — by the Spirit. As St. Thomas Aquinas said, “Grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it.” For example, in 1 Cor 12:28, St. Paul lists administration as a spiritual gift. We all know people who have a natural ability to organize, manage, and generally run things — all kinds of things — well: excellent administrators. But, the church isn’t a business or a committee. It needs to be administered well, but not in the same way as some of these other endeavors. So, God, through the Spirit, can perfect the natural ability of administration for use in the church. “Grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it.”

What is the purpose of the spiritual gifts? The purpose of the spiritual gifts is the common good. What is the implication here? A spiritual gift is not given to an individual for his/her private use and edification, but rather to share with the church for the upbuilding of all.

A poem by the Anglican divine John Donne comes to mind:

No man is an island,

Entire of itself;

Every man is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

As well as if a promontory were:

As well as if a manor of thy friend’s

Or of thine own were.

Any man’s death diminishes me,

Because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

The central notion of the poem is the interconnectedness of all humanity; we each, in some way, depend upon the other, and the contributions of each are essential to the welfare of the whole. Such is church and the spiritual gifts. Each of us here has some of the spiritual gifts; none has all. And so we share in a spiritual gift potluck — we pitch in what we have — so that everyone may partake and be nourished. From the seemingly most invisible or insignificant gift to the apparently most public and important gift, all are from God and all are essential to the common good.

Let me mention one often overlooked but absolutely essential spiritual gift; it’s not on St. Paul’s list simply because I think he assumed it in writing to the church. It is the gift of presence. Your being here matters for the common good. This parish, the catholic Church, the world depends upon your presence here in worship: your praise, your prayers, your confession, your Communion, your koinonia (fellowship), your learning and growth, your transformation into the likeness of Christ. The gift of presence is no small gift, no insignificant gift, and it is the essential foundation of every other gift given for the common good.

Let’s take a moment to look through the list of spiritual gifts that St. Paul mentions to the Corinthians. There is nothing particularly privileged about this list — there are others — but this one is characteristic, and it gives us a sense of some of the gifts needed for the common good and for the mission of the church.

The first gift actually precedes the list: no one can say, “Jesus is Lord” except in the Holy Spirit. If we read that claim in context, St. Paul seems to be comparing Christian worship to the pagan worship from which many in the Corinthian church had come. Imagine a pagan priest in some ecstatic state standing before an idol speaking and praising in either a known or an unknown tongue. Whatever he/she is saying, it is not, “Jesus is Lord.” It is only the Holy Spirit that leads one to make that confession.

Now, we must be clear here. There are many charlatans out there posing as Christians, posing as ministers, posing as those filled the the Holy Spirit, saying “Jesus is Lord.” And, yet they are devoid of the Spirit. Their invocation of the Lord’s name is nothing more than blasphemy. As Jesus himself said:

21 “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. 22 On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’ 23 And then will I declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness’” (Matt 7:21-23).

To truly say “Jesus is Lord,” is to make that confession not only with one’s lips, but with one’s life, as we pray in the General Thanksgiving. And no one can say “Jesus is Lord” with both lips and life without the gift of the Holy Spirit. This is the first spiritual gift that each of us must have, the grace to truly make the confession, “Jesus is Lord.”

Now, to the list proper, with just a brief word about each spiritual gift.

Wisdom

St. Paul does not define what he means by wisdom, but we have a library of wisdom literature in Scripture: Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, and, in the deuterocanonical books, Wisdom of Solomon, and Sirach. From these we can formulate a reasonable definition of wisdom. So, for example, from Proverbs:

10 The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,

and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight (Prov 9:10).

From this and from many other passages, we might describe wisdom as insight into the nature and will of God that brings us into a proper relationship of worship and piety. Wisdom is not primarily knowing about God, but rather knowing God himself. It is seeing things from God’s perspective and having insight into his will.

I would contrast wisdom with one of the classical spiritual illnesses of the heart: ignorance of God, in which one simply carries on his life as if there is no God.

Knowledge

The word St. Paul uses here is γνωσις (gnosis), a deep, inner apprehension of something. Spiritual knowledge would be living in the presence and with the awareness of God such that one orders one’s entire life around God. Involved in that is knowing how to order one’s life appropriately, knowing what God would have one do in any situation. The church needs people with knowledge to do pastoral care, spiritual direction, serve on vestry, teach classes, mentor, and a host of other activities. I would contrast knowledge with another of the illnesses of the heart: forgetfulness of God, in which one fails to engage with God, fails to seek his will, fails to live and move and have his being in God.

Faith

Well, all of us have faith, don’t we? Yes, but we might get a better appreciation of what St. Paul means if we speak of faithfulness instead of faith. What is the difference? Unfortunately, for us faith usually implies only or mainly right belief — believing the right things and having said the right things. But, faithfulness connotes a living relationship of integrity. Faithfulness to your spouse meaning more than having made vows, more than recognizing that you are actually married. It means more than just not having an affair. Faithfulness means leading a life of self-sacrificial service for your spouse, of putting your spouse’s welfare above your own, of loving devotion to your spouse regardless of the cost. We have people in the church who are faithful to God in this way. We call them saints: historical saints recognized by the whole church and contemporaneous local saints who are recognized only by those in the parish with them. But, to live a truly saintly life is a spiritual gift.

Healing

The elders (priests and bishops) in the Church have a sacramental ministry of healing through the rite of unction (see James 5:13-16). But, parallel to that there is a charismatic ministry of healing, i.e., the spiritual gift of healing not essentially related to ordination. There are simply some whose prayers for healing are especially effective. Though it is a bit outside our own Anglican tradition, I have read of elders (spiritual fathers) on Mt. Athos who can affect healing from a great distance. A pilgrim comes to seek healing for a loved one and the elder — even before the request is made — tells the pilgrim to go home, that his loved one is well. I do not have such a gift. Healing in which I am used by God comes, when it does, through prayer and anointing. But, I have no reason to doubt that some indeed have this unique gift of healing. Like all gifts, it is subject to the will of God; it is not a blank check, nor is it under the control of the one through whom the Spirit works.

Miracles

These would be manifestations of God’s power and glory in ways beyond physical healing. Exorcism might fall in the category of miracles. So might the reading of hearts, the ability to penetrate the secret needs or thoughts of another. Jesus did many miracles including multiplication of food, control of weather and other aspects of nature, appearing behind closed and locked doors. Any such “interruption” of the ordinary operation of nature might be considered a miracle.

Prophecy

We usually associate prophecy with foretelling the future. But, prophecy is also simply associated with seeing the present from God’s point of view and then speaking a word of guidance or correction/reproof. That is largely what the Old Testament prophets did. Prophecy is being particularly attuned to the voice of God and then speaking the word he gives.

Discernment of spirits

We have this word from St. John:

4 Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world. 2 By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, 3 and every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God. This is the spirit of the antichrist, which you heard was coming and now is in the world already. 4 Little children, you are from God and have overcome them, for he who is in you is greater than he who is in the world. 5 They are from the world; therefore they speak from the world, and the world listens to them. 6 We are from God. Whoever knows God listens to us; whoever is not from God does not listen to us. By this we know the Spirit of truth and the spirit of error (1 John 4:1-6).

St. John likely has something very specific in mind here. In the early church there were traveling prophets who went from church to church giving prophetic words. Some prophets were genuine — in the sense of being filled with the Spirit and speaking words in keeping with the orthodox faith — and some were not. So, St. John is cautioning the church to test every utterance (spirit) of such prophets. There was, in some cases, a very simple test: the confession that Jesus had come in the flesh. This is an acknowledgment of the incarnation, that Jesus was fully God and fully man. If a prophet cannot say yes to that, he is a false prophet and his spirit is that of antichrist. In John’s day, there was a notion that Jesus only appeared to be human, but was instead God in disguise. That is a false spirit. In our day, the Jehovah’s Witnesses do not rightly worship Jesus, nor do they believe that he is equal with God the Father. Again, that is a false spirit and is of the antichrist.

Some errors are not so clear cut. And for those, we need people who are gifted by the Holy Spirit with the gift of spiritual discernment.

Tongues and Interpretation of Tongues

By tongues, I understand St. Paul to refer to speaking languages of the spiritual realm and not of the natural realm. This might be a case of the Holy Spirit helping us in our weakness — when we don’t know how to pray as we ought — interceding for us with groanings too deep for words (cf Rom 8:26-27). It might be an example of exuberant praise for which no human language is sufficient. It might be an example of God giving a prophetic word in a spiritual language to make it clear that the word is from God and not from man. And there are certainly other reasons why the gift of tongues might be given.

It is a powerful gift, because, as St. James writes, the tongue has great power. And, because of that that, it is a gift that must be carefully controlled when used in public worship. The most basic condition for the public use of tongues is that an interpretation of the utterance be given also. And remember why: the spiritual gifts are for the common good. If I do not understand what was spoken in a tongue, it is of no benefit to me whatsoever. But, I can benefit from the translation/interpretation.

Summary

We started this lesson with the fundamental notion of Christian identity: that we are children of God. That familial relationship is both a matter of status — given to us in full at baptism — and nature, into which grow through our cooperation with the Holy Spirit. The fruit of the Spirit is the outward evidence that we are indeed growing in the divine nature, growing in our likeness to Christ. We grow not only individually but in fellowship with one another. And, in that fellowship, in the church, the Spirit gifts believers with a variety of gifts needed for the common good — always for the common good.

St. Paul tells the Corinthians to earnestly desire the higher gifts, though he doesn’t specify which those are. I see no reason that we should not aspire to those as well and to pray for them, provided we seek them not for our glory but for the common good. Then, of course, Paul goes on to say, that there is an even more excellent way than even the highest of the Spiritual gifts: the way of love. That, we should all seek.