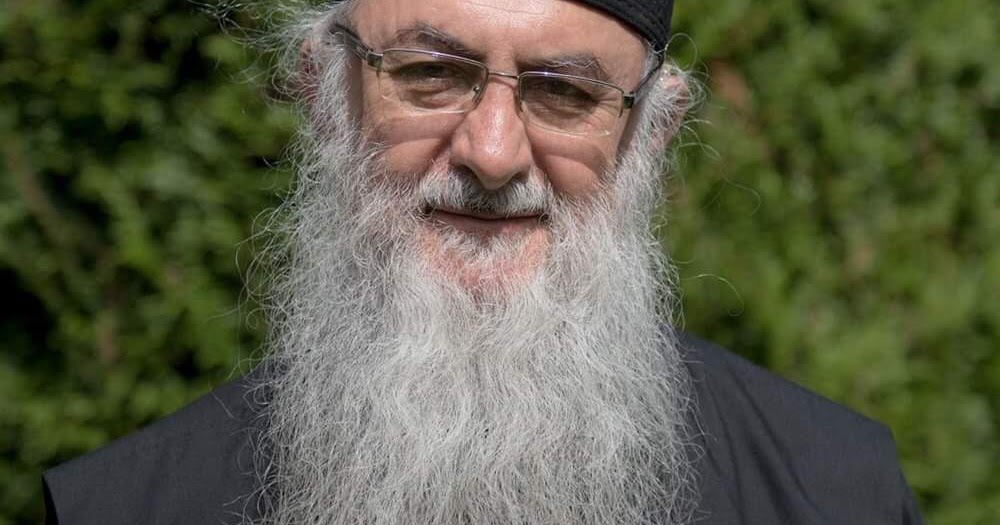

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

A Few Thoughts on Psalm 119

(Judges 2, Psalm 119:49-72, Galatians 4)

Collect

O Lord, from whom all good proceeds: Grant us the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may always think those things that are good, and by your merciful guidance may accomplish the same; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

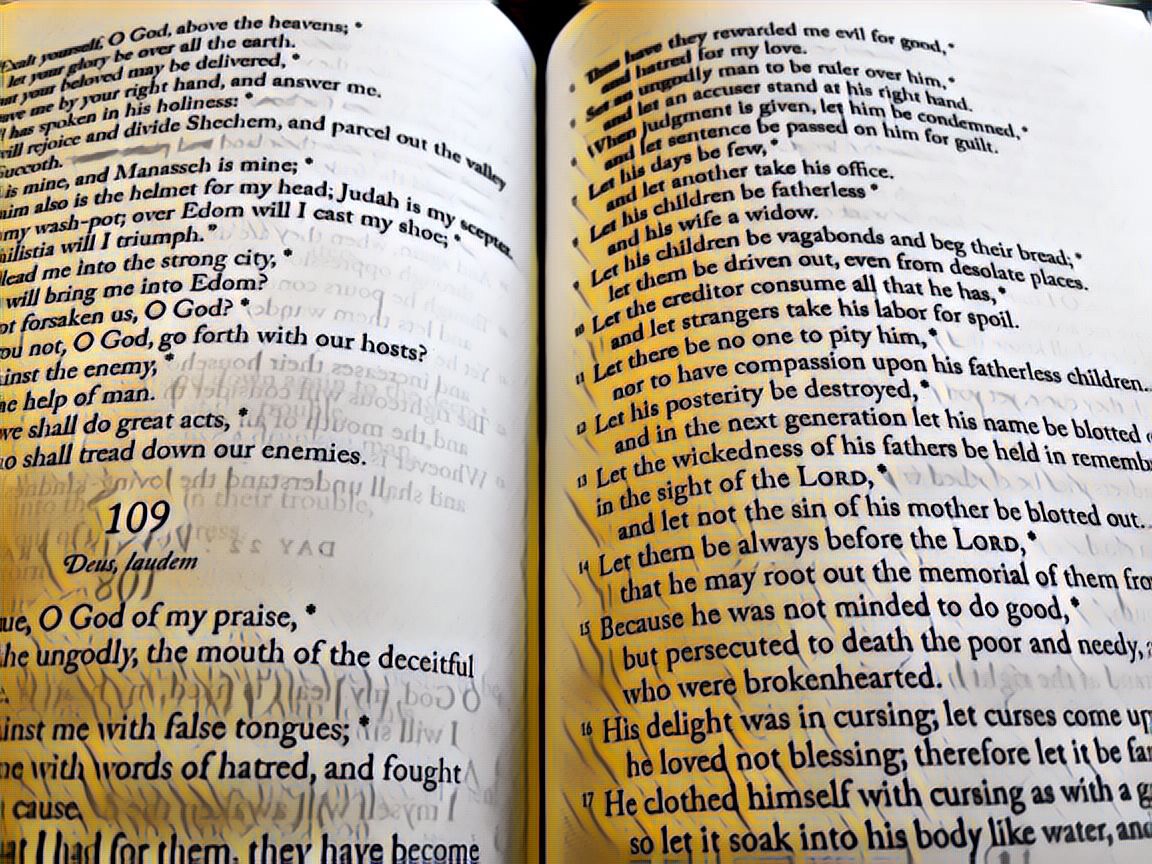

105 Your word is a lantern to my feet *

and a light upon my path.

106 I have sworn and am steadfastly purposed *

to keep your righteous judgments.

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Are you aware that the state of Tennessee has a Poet Laureate — 85 year old Margaret Britton Vaughn of Bell Buckle, Tennessee? Poet Laureate is an honorary position, a political appointment to acknowledge one’s literary skill and achievements and to put them to use for the common good. According to wikipedia:

In 1995, the Tennessee state legislature selected Vaughn to be Tennessee’s poet laureate citing many of the plays, collections, and books Vaughn wrote throughout her career and her performances and outreach throughout the state of Tennessee. As poet laureate, Vaughn wrote Tennessee’s bicentennial poem, inaugural poems for many Tennessee governors including current governor, Bill Lee, and a poem to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the US Air Force (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Britton_Vaughn, accessed 06/11/2024).

Now, imagine Vaughn receiving a call from our Governor to commission a poem with these requirements:

The poem must consist of exactly twenty-six verses.

Each verse must consist of exactly eight lines.

Each line of the first verse must begin with the letter A, each line of the second verse with B, and so on throughout the alphabet, with each line of the final verse beginning with the letter Z. (For those interested in such things, a poem having that structure is called an acrostic.)

The theme of the entire poem must be the goodness, truth, and beauty of our state laws as compiled in the Tennessee Code Annotated, and the wisdom, mercy, and justice of the legislators who authored those laws.

Could such a thing be done? Probably. Should such a thing be done? Probably not. Would anyone want to read it if it were done? Almost certainly not, except possibly to see how a poet “pulled off” such a remarkable and bizarre assignment.

And yet, that is almost exactly what we have in Psalm 119. It is an acrostic poem of twenty-two verses, each verse having eight lines. Each verse corresponds to one of the letters in the Hebrew alphabet, and each line in that verse begins with the appropriate letter: verse one with aleph, verse two with bet, and so on through verse twenty-two with taw. Its theme is the goodness, truth, and beauty of God’s law, and the wisdom, mercy, and justice of God who gave it. It can be done; it has been done under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit: so we believe, though that doesn’t necessarily mean we want to read it.

I must confess to experiencing a sense of…dread isn’t quite the right word — perhaps weariness is better — as I’ve seen Psalm 119 looming on the near horizon in the Daily Office Lectionary as it does at least six times each year. I know the journey through it will be long and the “scenery” won’t change much on that journey. It has seemed to me to be the Psalter’s equivalent of a road trip across Kansas: long and “Hey, look, another corn field!” I’m sorry if that scandalizes you; I’m just being honest.

But, my attitude is evolving, and I’m gaining more appreciation for the Psalm. The holy repetition in it — caused both by form and content — seems less monotonous to me now, and just more comfortably familiar, like ordinary time spent with a good friend: not always exciting, but deeply fulfilling. Even the acrostic form of the Psalm seems less artificial than before and more theologically significant. God spoke the world into being. God revealed his commandments for Israel as the Ten Words. The second Person of the Trinity who took on flesh to dwell among us is described/identified as the λογος, the Word. There is something profoundly significant about language, its letters and its words. So it makes a certain sense that God’s Law is extolled in Psalm 119 using all the letters of the Hebrew alphabet in order. It honors language as a central means by which God has made himself known. As for content, the Psalm’s praise of the Law is not so much about individual rules and regulations as it is about God’s self-revelation to us of his character: the God who wants humans to flourish, who wants justice to prevail, who wants to guide the world into the way of truth, who, in his mercy, loves us. Who wouldn’t want to know that God? And who wouldn’t want to meditate on his character by reading and praying and chanting Psalm 119?

Earlier, I jokingly compared the Psalm to a road trip across Kansas. Truth be told, even though Dorothy herself was bored with Kansas early in the film, when thrust out of it into the Land of Oz, she realized that there’s no place like home, and she wanted nothing more than to return there. To mix metaphors a bit, Psalm 119 is something like the Yellow Brick Road, a path that guides us on our journey, or maybe better still, in a biblical metaphor from the Psalm itself, a lantern to our feet and a light upon the path.

Our Daily Office lectionary appoints three stanzas — three letters — of Psalm 119 for Morning Prayer today. I would like to draw just a thought or two from each of those stanzas for our reflection.

Zayin: Psalm 119:49-56 — Memory

In June of 1969, memory expert Harry Lorayne appeared on the Mike Douglas Show, an afternoon variety and talk show popular at the time. Before the show, Lorayne was introduced to each member of the studio audience by name, and he attempted to memorize all their faces and names. Then later in the show, the host, Mike Douglas, selected five members of the audience at random, had them stand, and asked Lorayne their names. He correctly named all five: Murdoch, Folderhour, Yesletski, Ouston, and Tomszack.

That has been fifty-five years ago next week, and I still recall all those names. So does my brother who was watching the show with me. For over five decades we have made a game of it. At random times, one of us will ask the other, “Do you remember the names?” as a challenge, and so they have stuck with us. This is a very low level sort of memory: memory as recall of meaningless, disconnected bits of information.

In this stanza of Psalm 119, the psalmist is interested in memory, but memory of a far more significant kind: divine memory and sacramental human memory. And there is a challenge here, too, not unlike that between my brother and me. The psalmist says, “I remember, Lord. Do you?”

49 O remember your word to your servant, *

in which you have caused me to put my trust.

50 This is my comfort in my trouble, *

for your word has given me life.

51 The proud have held me exceedingly in derision, *

yet I have not turned aside from your law.

52 For I have remembered, O Lᴏʀᴅ, your judgments from of old, *

and by them I have received comfort.

The psalmist is in trouble; he is being oppressed by the proud. And yet he is not overcome, not in despair. What is his source of comfort in his troubles? He remembers. He remembers the word of God in which he has placed his trust, and he remembers the judgment of the Lord — the vindication of the psalmist as being in the right — from times past. This is not memory as mere recall; it is not five random names. It is a sacramental type of memory, a memory that leads to re-presentation and participation. More about this in bit.

In and through his memory the psalmist “challenges” God to remember: O remember your word to your servant. Again, the psalmist is not interested in mere recall. For God to remember, is for God to act: to judge in the psalmist’s favor, to act to deliver him. That notion of divine memory as God’s redemptive action underlies the Exodus account:

23 During those many days the king of Egypt died, and the people of Israel groaned because of their slavery and cried out for help. Their cry for rescue from slavery came up to God. 24 And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. 25 God saw the people of Israel—and God knew (Ex 2:23-25, ESV).

God’s memory is God’s covenant faithfulness in action to deliver his people. That’s what the psalmist is calling out for: O remember your word to your servant. God’s memory is divine, redemptive action; our sacramental memory is participation in God’s action.

That notion of divine and human memory lies at the heart of the Eucharist. Part of the Eucharist prayer is called the anamnesis, the remembering, because it is precisely that, a recounting of God’s redemptive action in Jesus Christ.

Therefore, O Lord and heavenly Father, according to the institution of your dearly beloved Son our Savior Jesus Christ, we your humble servants celebrate and make here before your divine Majesty, with these holy gifts, the memorial your Son commanded us to make; remembering his blessed passion and precious death, his mighty resurrection and glorious ascension, and his promise to come again (BCP 2019, p. 117).

And in our anamnesis, in our remembering, we are calling upon God to remember, to act once again in this moment so we might not just recall the redemptive work of Jesus Christ in the past, but participate in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ in the present:

And we earnestly desire your fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this, our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving; asking you to grant that, by the merits and death of your Son Jesus Christ, and through faith in his Blood, we and your whole Church may obtain forgiveness of our sins, and all other benefits of his passion (BCP 2019, p. 117).

This is not mere recall; this is sacramental remembering in which we participate in that redemptive act once again, in which it becomes present for us once again so that we may receive all the benefits of Christ’s passion.

All of that is present as a seed in Psalm 119 — as a seed that will be planted in the earth and rise again to new life in the Gospel.

Heth: Psalm 119:57-64 — Portion

The notion of memory continues in this stanza of the Psalm also, but there is another matter that asks for our attention. Let me start with a passage from Deuteronomy to put things in context.

Deuteronomy 10:6–9 (ESV): 6 (The people of Israel journeyed from Beeroth Bene-jaakan to Moserah. There Aaron died, and there he was buried. And his son Eleazar ministered as priest in his place. 7 From there they journeyed to Gudgodah, and from Gudgodah to Jotbathah, a land with brooks of water. 8 At that time the Lord set apart the tribe of Levi to carry the ark of the covenant of the Lord to stand before the Lord to minister to him and to bless in his name, to this day. 9 Therefore Levi has no portion or inheritance with his brothers. The Lord is his inheritance, as the Lord your God said to him.)

The Levitical priests were not given a hereditary allotment of land in Israel; rather the Lord, and the service of the Lord, was their inheritance, their portion. The other tribes got fields and valleys and rivers. The Levites got to carry the ark of the covenant, got to stand before the Lord to minister to him and to bless in his name. That notion persists even now. The word “clergy” is from the Greek κληρικός which means inheritance or portion; the priests’ portion was then and is now God.

Now, hear the psalmist:

57 You are my portion, O Lᴏʀᴅ; *

I have promised to keep your law.

58 I made my humble petition in your presence with my whole heart; *

O be merciful to me, according to your word.

You are my portion, O LORD. Was the psalmist a Levite? It is possible. Some of the Psalms are attributed to Asaph, one of the leaders of the Levitical singers, though Psalm 119 is not. I suspect the psalmist — likely not a Levite — is simply saying that his highest good, his supreme value is in the Lord. St. Benedict instructed his followers to “prefer nothing to Christ.” That gets at the same idea. St. Paul said it this way:

Philippians 3:4–11 (ESV): If anyone else thinks he has reason for confidence in the flesh, I have more: 5 circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee; 6 as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless. 7 But whatever gain I had, I counted as loss for the sake of Christ. 8 Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith— 10 that I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, 11 that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead.

That is a man whose only portion in life was the Lord. That is what the psalmist holds out before us — not just for Levites or priests, but for all of us.

Teth: Psalm 119:65-72 — Affliction

Now the Psalm brings us to a question which bedevils many: If God is good and loves us, if God is all-powerful, then why does God allow suffering, particularly the suffering of the innocent and the good? I don’t want to answer that simplistically or callously. But I do want to suggest that the psalmist knew something about suffering and even found value in it. Hear what he says:

67 Before I was afflicted I went astray, *

but now I keep your word.

71 It is good for me that I have been afflicted, *

that I may learn your statutes.

The best, short answer to the “problem of theodicy” — Why does a loving, all-powerful God permit suffering? — is simply this: for our salvation. Suffering points to the ubiquity and gravitas of sin; sin affects us all and it is deadly serious. Suffering breaks the hardened heart. Suffering crushes pride. Suffering falsifies our claims of autonomy and self-sufficiency and drives us to our knees in repentance, into the arms of a loving God. The only meaningless suffering is that suffering which is not accepted as from the hand of God, that suffering which is not allowed to do its good though painful work in us.

This doesn’t imply that we understand the exact purpose and spiritual dynamics of each particular instance of suffering, but simply that even in the midst of it we believe that God is good and that he intends only our good. Listen to the psalmist again:

66 O teach me true understanding and knowledge, *

for I have believed your commandments.

These are not the words of someone who yet understands his suffering, but of someone who believes in the graciousness of God in the midst of suffering and who seeks understanding of it: “faith seeking understanding,” as St. Anselm said. According to the psalmist, there is a level of understanding that only comes in the midst of suffering:

71 It is good for me that I have been afflicted, *

that I may learn your statutes.

So, in this brief portion of Psalm 119, we have seen the importance of sacramental memory, of holy portion, and of saving affliction. It is — if the sheer length of it doesn’t put us off — a powerful Psalm, truly a lantern to our feet and a light upon our path.

Amen.