Session 1 — Plays and Symphonies (Isa 2:1-5)

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

Advent with Isaiah: Session 1 — Plays and Symphonies

Isaiah 2:1-5

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

Blessed Lord, who caused all Holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and the comfort of your holy Word we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which you have given us in our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Two Convictions

Astrophysicist Carl Sagan wrote: “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” He meant that most of the constituent elements in apples and flour and sugar were forged in ancient stars that exploded and scattered those elements abroad with some of them making up this planet we call earth. So, you have to have a universe of ancient stars before you can bake an apple.

The same holds true with household repairs. You can never do the job you started until you finish another one before it.

And the same is true when teaching a class. We are here to discuss Advent with Isaiah. But, to do that, I find that we must first go back far earlier than Isaiah and work our way forward. We’ll “create” the universe of Scripture and then we’ll bake a delicious pie.

I want start with two hermeneutical convictions — convictions about how we find meaning in Scripture. The two aren’t separate; they are more like the two sides of a single coin, but I’ll pull them apart to make them clear.

Conviction 1: Jesus makes precisely what sense he makes only in the context of the whole story of Scripture. Without the Hebrew scriptures, Jesus makes no sense.

Conviction 2: The story of Scripture makes what sense it makes only when read through the lens of Jesus. Without Jesus, the Hebrew scriptures make no sense.

I know this has a sort of chicken-and-egg quandary about it: you can understanding Jesus only when you understand the story of Scripture, and you can understand the story of Scripture only when you understand Jesus. So, which comes first? Where do you break into the circle? N. T. Wright talks about a cartoon showing a chicken and an egg talking. One says to the other: “Well, can we just stop asking? We’re both here now, so what does it matter?” Yes, you need the Hebrew Scriptures to understand Jesus and you need Jesus to understand the Hebrew Scriptures, but they’re both here now. Read them together and you won’t go wrong. Separate them, and theological disaster is certain.

These two convictions — that you can understand Jesus only when you understand the story of Scripture, and that you can understand the story of Scripture only when you understand Jesus — come from Jesus himself and from Scripture itself. We’ll look at two places this appears, one from Jesus and one from St. Paul.

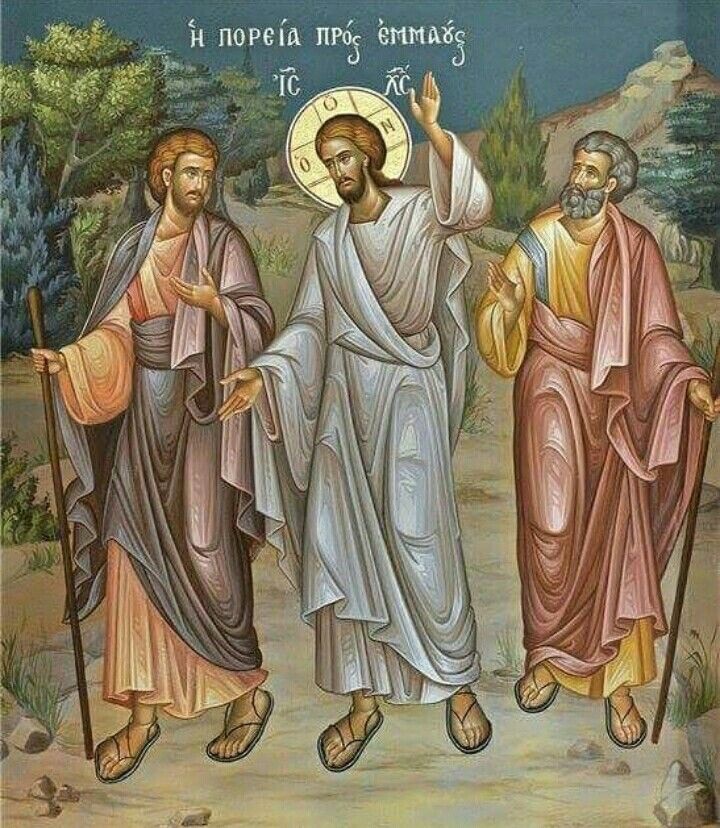

On the Road to Emmaus

Let’s start with a well-beloved event narrated by St. Luke, a post-resurrection appearance of Jesus.

13 That very day two of them were going to a village named Emmaus, about seven miles from Jerusalem, 14 and they were talking with each other about all these things that had happened. 15 While they were talking and discussing together, Jesus himself drew near and went with them. 16 But their eyes were kept from recognizing him. 17 And he said to them, “What is this conversation that you are holding with each other as you walk?” And they stood still, looking sad. 18 Then one of them, named Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” 19 And he said to them, “What things?” And they said to him, “Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, a man who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, 20 and how our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. 21 But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since these things happened. 22 Moreover, some women of our company amazed us. They were at the tomb early in the morning, 23 and when they did not find his body, they came back saying that they had even seen a vision of angels, who said that he was alive. 24 Some of those who were with us went to the tomb and found it just as the women had said, but him they did not see.” 25 And he said to them, “O foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! 26 Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” 27 And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself (Luke 24:13-27, ESV throughout unless otherwise noted).

The two on the road to Emmaus, Cleopas and his companion, are confused about the events surrounding Jesus; his crucifixion has thrown their hopes into disillusionment, and the reports of angels, a missing body, and claims of resurrection have muddled things even further. And what does the “stranger” with them do? He opens to them the Scriptures beginning with Moses (the Pentateuch) and the Prophets and shows them that the events surrounding Jesus make what sense they make, only in the context of the whole story of Scripture. Rightly understand Scripture and you will rightly understand Jesus. Or said negatively: if you don’t understand Scripture, you will not understand Jesus.

The Veil Lifted

St. Paul was commissioned by Jesus specifically to be the Apostle to the Gentiles. Yet, Paul never flagged in his concern for his fellow Judeans. His practice and his mantra were the same: to the Jews first and also to the Greeks. So, he agonized over the ongoing rejection of Jesus by most of his fellow Jews, and he pondered why that might be so. You can read Romans 9-11 for a detailed exposition of this. But it isn’t only in Romans; listen to these words from 2 Corinthians:

12 Since we have such a hope, we are very bold, 13 not like Moses, who would put a veil over his face so that the Israelites might not gaze at the outcome of what was being brought to an end. 14 But their minds were hardened. For to this day, when they read the old covenant, that same veil remains unlifted, because only through Christ is it taken away. 15 Yes, to this day whenever Moses is read a veil lies over their hearts. 16 But when one turns to the Lord, the veil is removed. 17 Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. 18 And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit (2 Cor 3:12-18).

St. Paul says his fellow Jews cannot read and understand their own Scriptures because their minds are hardened and their hearts veiled. It is only when one turns to the Lord Jesus that the veil is lifted and the Scriptures make sense. You can only understand the Scriptures through the lens of Jesus.

So, there you have my two convictions about Scripture from Scripture itself.

Conviction 1: Jesus makes precisely what sense he makes only in the context of the whole story of Scripture. Without the Hebrew scriptures, Jesus makes no sense.

Conviction 2: The story of Scripture makes what sense it makes only when read through the lens of Jesus. Without Jesus, the Hebrew scriptures make no sense.

In Advent, it is fitting to begin with Conviction 1, to ask these questions: What is the whole story of Scripture in which Jesus makes sense? How might Jesus have told the story to his companions on the way to Emmaus?

The Story of Scripture: A Drama in Five Acts

Up until now, I have assumed something that many people — both Christian and non-Christian — do not necessarily take for granted: that Scripture is a coherent narrative that tells a single story, though that story is complex and multigenerational and multidimensional. Scripture is a grand, sweeping drama with Jesus at its climax. The Bible isn’t always considered that way. Some see it as a rule book or perhaps as an instructional manual; look things up as needed — a sort of ancient moral and religious YouTube. Some see it as a collection of ancient myths or moralistic fables. Some see no pattern or coherence in it at all. But for us, it is a narrative — the narrative — the drama of God and man.

Because it is a drama, many find it helpful to consider it as a play with various acts. There are many ways to divide the narrative, but I find the way often used by N. T. Wright to be straightforward and helpful. He describes the narrative as a play in five acts:

ACT I: Creation

ACT II: Fall

ACT III: Israel

ACT IV: Jesus

ACT V: Church

Today, I want us to consider the first three acts — Creation, Fall, and Israel — especially in relationship to Jesus.

ACT I: Creation

God created everything that is; for us that is a given starting point. But why? Why did God create at all? Here is how St. Paul might answer that question:

15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. 16 For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him (Col 1:15-16).

Creation — physical and spiritual, visible and invisible — is for Christ. Creation is to the glory of the Son of God; it shows forth his praise. And what of man in creation? What is man’s unique purpose? We — male and female — are to bear the image and the likeness of God, not least by being God’s vicegerent, his authorized representative on earth to act on his behalf as priest, prophet, and king. There is even more here. Paradise/Eden was the place of overlap of heaven and earth, the place where God dwelt among his people. It was to expand outward into the world as Adam and Eve, and later their offspring, subdued and tended creation so that God’s kingdom on earth might be as God’s kingdom in heaven. And that points us toward Christ who came announcing that, in and through his presence, the Kingdom of Heaven was at hand, that in him and through him God was once again dwelling with men.

The Church Fathers thought of Adam and Eve as innocent but not yet as perfect. When I say not perfect, I don’t mean flawed or deficient; I mean not complete, just as a baby or infant is not yet perfect. Think innocent and immature and you get the picture. A baby has much growth ahead of it: much to learn, many skills to develop. This is a distinction the Church makes between the image and likeness of God. We are made in the image of God in that we are rational beings who have the spiritual capacity to bear the likeness of the Son of God. Some of you may remember the instant cameras of the 1960s. Snap a photo and the undeveloped film shoots out the back, a blank, black negative. The image is already there on the film. But, over the next several seconds the likeness begins to form and show as chemicals react. Image and likeness: man was made in the image of God with the intent that man would mature into the likeness of the Son. So, this means that man, formed for Christ, made in the image of God, was intended to grow into Christlikeness and to point all creation — in heaven and on earth — toward Christ. I might say that this is still true: that baptism — new birth, new creation — renews the image of God in man and that man is intended to grow from there into the perfect image of Christlikeness.

ACT II: Fall

We do not know how long man persisted in his state of innocence, that is, in obedience to God and in fulfillment of his vocation. But that did not last. We need not rehearse all the details of what we call “the Fall,” though we should be clear about its consequences. How did man and creation change through the Fall? Man became subject to death, sin, and the fallen powers. Man lost his original innocence and squandered his vocation. Creation itself was subjected to futility; it is out of joint, subjected to the ravages of entropy — the wearing out and running down of all things.

All of this raises an important question: was Act I a failure, after all — God’s Plan A gone awry? What do you think? The Creation was not a failure. Let me suggest two reasons for that conviction. First, creation perfectly expressed the will of God for something other than God to exist for the glory of the Son; that there is something other than God and that the something is oriented toward God and shows forth, even imperfectly, the glory of the Son rules out failure as the verdict on creation. As for humankind, they are still the image-bearers of God — imperfectly so, but image-bearers nonetheless. They are still signposts — broken signposts as N. T. Wright says — pointing toward the Son. All of creation, even in its fallen state, points achingly toward its telos, toward its proper end. It has lost its way to get there on its own, but the proper end is at least dimly remembered. That raises the question of how to get man and all of creation back on track. It’s time for Act III.

ACT III: Israel

In Act III, God’s calls a man and his wife — harkening back to Adam and Eve — to be the nucleus of a people who would be for God a holy nation, a kingdom of priests. He promised Abraham a people and a place (a land): a people with whom God would dwell and a place in which God’s kingdom — his righteous rule — would be made manifest to all other peoples.

The story of Israel is long and winding. What are some key points in it — considered chronologically?

1. The birth of Isaac and the renewal of the covenant

2. The birth of Jacob and the renewal of the covenant

3. The birth of the Patriarchs

4. Exile in Egypt

5. The Passover and the Exodus (1200s BC — Moses, Exodus, Joshua)

6. The Law

7. The Wilderness experience and the Conquering of the Promised Land

8. The Judges (1100s BC)

9. The United Kingdom: Saul and David (1000s BC)

10. The Divided Kingdom: Solomon, Rehoboam, Jeroboam (900s BC)

11. Various Kings in both Israel and Judah (800s-700s)

12. Fall of Israel/Samaria to Assyria (722 BC)

13. Fall of Judah to Babylon (587 BC)

We could spend many hours filling in details, but it is the grand sweep we are interested in. And, in Advent, we are also interested in the Prophet Isaiah. Where does he appear in the timeline? Well, that is a matter of much debate. We can place the beginning of his ministry during the reign of King Ahaz of Judah (reign c. 736-715 BC). That means that Isaiah began his ministry shortly before the fall of the Northern Kingdom, and he witnessed, at least second hand, its destruction. The end of Isaiah’s ministry is the question. His prophecies include the fall of Judah, the Babylonian captivity, and the return of the exiles to Jerusalem, a period from 587-539 BC. So, Isaiah’s prophecies cover roughly a 200 year period, a very unlikely lifespan. So what are the possibilities most serious considered to explain this?

Many scholars have concluded that the book we call Isaiah is a compilation of similarly themed prophecies from either two or three different prophets. The book is often broken down like this:

Chapters 1-39: Isaiah

Chapters 40-55: Second Isaiah

Chapters 56-66: Third Isaiah

The other major notion is simply that the one Isaiah who began his ministry during Ahaz’s reign was granted a vision of what was to come long beyond his own death, in other words that he was a prophet not only in the sense of one who tells the truth of current events from God’s perspective but also as one who foresees coming events and their spiritual import. I have no problem with either option, but I see no reason to discount a single Isaiah who functioned as a prophet in the fullest sense. Even if we accept three Isaiahs, there is an irreducible element of foretelling if the book is in any way Christological, that is, if it points to Christ, as it surely does.

Now, let me pose the same question about Act III as I did about Act II: was it a failure? The story of Israel — in the Old Testament — ends incompletely and disappointingly. Ten of the twelve tribes have been lost forever, assimilated by other peoples and nations. The two remaining tribes, which are now called the Judeans, are greatly diminished in scope and power; they are occupied by a succession of foreign powers and have no Davidic king as promised. Worse still, God no longer dwells in the midst of them; the Holy of Holies in the rebuilt Temple is empty and their worship is simply a ritual. The promises of the covenant have not been fulfilled. If Israel was to be the solution of man’s fall, it seems like something has gone drastically wrong. So, was Israel a failure, Plan C gone to rack and ruin? Again, I must say no. Israel was not to be the people who would solve the problem of the fall itself, but rather the people through whom God would come to solve the problem himself. Israel was the people through whom the Messiah would come, the Messiah who would deliver all men from sin, death, and slavery to the powers; the Messiah who would inaugurate the Kingdom of God and who would himself be the one in whom God and man would dwell together. So, ultimately, Israel points directly toward Christ and cannot be understood apart from Christ. And, just as clearly, Christ cannot be understood apart from the story contained in the Hebrew Scriptures.

And that brings us around again to our two convictions: Jesus can be understood only in context of the whole of Scripture and the whole of Scripture can be understood only in context of Jesus. The Old Testament — not least Isaiah — points toward Jesus, and Jesus is the climax and fulfillment of the Old Testament.

Isaiah

Now, with this background, we can turn our attention to the text. We will start by taking a few minutes to read Isaiah 1 as the context for the today’s lesson, Isaiah 2:1-5. As you read with your table group, I would like you to consider a few questions:

1. What is the state of Jerusalem and Judah as Isaiah describes it?

2. What is the relationship between worship and social justice?

3. What does God want/expect from the people?

4. What does God plan to do?

It would be helpful to point out some specific verses that lead to your answers.

[Discuss Isaiah 1]

And now — at last — we come to the text for today’s lesson, Isaiah 2:1-5.

1 The word that Isaiah the son of Amoz saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem.

2 It shall come to pass in the latter days

that the mountain of the house of the Lord

shall be established as the highest of the mountains,

and shall be lifted up above the hills;

and all the nations shall flow to it,

3 and many peoples shall come, and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord,

to the house of the God of Jacob,

that he may teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go forth the law,

and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

4 He shall judge between the nations,

and shall decide disputes for many peoples;

and they shall beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war anymore.

5 O house of Jacob,

come, let us walk

in the light of the Lord.

Imagine a composer working on a great symphony. The first three movements are complete, though the third one doesn’t have the typical dancelike motif. Instead, it is somber, and it ends without resolution but with a whispering, whimpering discord. And then, tragedy strikes; the composer dies before finishing the fourth and final movement. But, he has left behind some hints, some notes, a musical theme, which he had planned to develop fully. And these notes are hopeful, upbeat, a glorious fulfillment of all that had gone before. It provides resolution and harmony.

This is a good analogy for the Old Testament, for Acts I through III of the drama of Scripture, if I may mix metaphors from drama to symphony. The story of Israel ends unfinished, on a minor note, with discord and not harmony. Judah is under occupation with no Davidic king on the throne and the temple of God is empty of the presence of God. But, the composer has left behind some notes, a prophetic them which is yet to be fully developed; and it is glorious and hopeful. That is what we get in Isaiah 2:1-5.

Notice in verse 2 that the fulfillment of this vision is yet to come; it is for the latter days. And that should strike a chord with us:

1 Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, 2 but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world (Heb 1:1-2).

The latter day, the last days, are the days of Acts IV and V of the great drama — the acts of Jesus and the Church. Isaiah sees that the story of Israel is incomplete and will reach its fulfillment only in his future. And what will be the sign of this fulfillment?

…and all the nations shall flow to it,

3 and many peoples shall come, and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord,

to the house of the God of Jacob,

that he may teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go forth the law,

and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem (Is 2:2b-3).

In the latter days, God will no longer be just the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but the God of all peoples as was intended from creation. So, this is not only the fulfillment of God’s covenants with Abraham and David, but with Adam and with all creation. And again, this finds its fulfillment only in Jesus, as we sing in the canticle Dignus Es:

Splendor and honor and kingly power*

are yours by right, O Lord our God,

For you created everything that is,*

and by your will they were created and have their being;

And yours by right, O Lamb that was slain,*

for with your blood you have redeemed for God,

From every family, language, people, and nation,*

a kingdom of priests to serve our God.

And so, to him who sits upon the throne,*

and to Christ the Lamb,

Be worship and praise, dominion and splendor,*

for ever and for evermore. Amen (BCP 2019, p. 84).

Now we come to a portion of Isaiah’s prophecy which requires us to modify Wright’s five act play. Remember the outline:

ACT I: Creation

ACT II: Fall

ACT III: Israel

ACT IV: Jesus

ACT V: Church

We need a sixth act: the age to come — the age in which heaven and earth are united (Rev 21, 22) and in which God is all and in all (1 Cor 15:28). Only then will all disputes be resolved, only then will perfect peace reign. That is the last act of the drama, the fourth movement of the unfinished symphony, the fulfillment of all promises in Christ. That is what Isaiah saw in his vision. It is what Jesus’s first Advent set into motion, and what his second Advent will bring to fulfillment.