Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

This Is the Message: A Homily on 1 John 3:11-24

(2 Kings 6, Ps 75, 1 John 3:11-4:6)

Collect

O God, our refuge and strength, true source of all godliness: Graciously hear the devout prayers of your Church, and grant that those things which we ask faithfully, we may obtain effectually, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

In its two thousand year history, the Orthodox Church has formally recognized only three — perhaps four — theologians. The most recent, Saint Symeon the New Theologian, died in 1022. Today, in the post-Enlightenment West, we tend to use the term theologian quite loosely to mean someone who has made an academic study of God and of things religious, to mean someone who knows many facts about what others throughout history have thought and said about God. By that definition, even an atheist can be a theologian, and there are, indeed, some who are. But not so in the Eastern Church. Amongst the Orthodox, a theologian is not one who knows about God, but rather one who knows God — in and through Christ — directly, immediately by encounter and fellowship and revelation, through prayer and purity of heart.

The first of those recognized by the Church as theologian is St. John the Evangelist, the beloved disciple of our Lord. It is easy to see how he fits the Orthodox definition of theologian, or perhaps how the definition was formulated around him. Did he know God directly by encounter and fellowship?

Listen to the opening of his first epistle:

1 That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life— 2 the life was made manifest, and we have seen it, and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and was made manifest to us— 3 that which we have seen and heard we proclaim also to you, so that you too may have fellowship with us; and indeed our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ (1 John 1:1-3, ESV throughout unless otherwise noted).

St. John knew God incarnate by sight, by touch, by hearing.

Did he know God by revelation through prayer? Listen to the opening of The Apocalypse:

1 The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants the things that must soon take place. He made it known by sending his angel to his servant John, 2 who bore witness to the word of God and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, even to all that he saw (Rev 1:1-2).

St. John says that this revelation, this vision, occurred when he was in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day, almost certainly in a time of prayer and worship, perhaps Eucharistic worship. Certainly, St. John knew God by revelation and through prayer.

So, yes, St. John is the archetypal theologian in the true sense. That shines through in his writings: in the fourth Gospel; in his three epistles, most clearly in the first of them; and in The Revelation.

There are common themes that emerge from St. John’s encounters with God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit; amongst them these three are prominent: life, light, and love. He introduces two of these themes in the prologue of his Gospel:

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. 4 In him was life, and the life was the light of men. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it (John 1:1-5, emphasis added).

The third theme comes in Jesus’ discourse with Nicodemus:

16 “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life (John 3:16, emphasis added).

Light, life, and love: these three lie at the heart of St. John’s theology because they are what he saw in God incarnate. For St. Paul it is faith, hope, and love; for St. John the Theologian, it is life, light, and love.

There are implied dichotomies in St. John’s theology. He writes:

5 This is the message we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light, and in him is no darkness at all (1 John 1:5).

St. John didn’t write, but could have: “in him is no darkness at all; in him is no — whatever the opposite of love is — at all.” But, such negative conditions do exist, and St. John knew it. They are there in his Gospel, in his epistles, in The Revelation. Jesus came as light into a world shrouded in darkness. Jesus came as life into a death-impregnated world. Jesus came as love into a world twisted by hatred, envy, and indifference. He came to conquer the powers of darkness, death, and hate. He came to redeem us from slavery to darkness, death, and hate. He came to shine light into our darkness, to lead us out of death into eternal life, to teach us and empower us to love God and our neighbor. And that brings us to our text today, 1 John 3:11-24.

11 For this is the message that you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another. 12 We should not be like Cain, who was of the evil one and murdered his brother. And why did he murder him? Because his own deeds were evil and his brother’s righteous. 13 Do not be surprised, brothers, that the world hates you. 14 We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death. 15 Everyone who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him (1 John 3:11-15).

Here, St. John plunges us headlong into the heart of the great conflict. We are commanded to love in a world that will reciprocate with hatred and violence. We are to live — to proclaim resurrection — in a world headed toward the grave. And the inevitable result of our decision to love and to live is a conflict that, by all outward evidence, we will loose. Evil will seem to win because we will be hated and we will be killed. Our very righteousness will provoke the world to murder. We see that with Jesus and in every previous generation throughout history flowing backward all the way to Cain.

From the beginning, St. John writes — from creation — we have heard the message that we should love one another, with the implication that Cain knew this commandment, as well. So, why did he violate the commandment and murder his brother? St. John gives two, tantalizing answers: (1) Cain was of the evil one, and (2) Abel’s righteousness shone a light on Cain’s evil. I don’t know fully what it means that Cain was of the evil one, but the language is evocative of more than a passing acquaintance. By comparison, one cannot be of Christ casually, without firm resolve and commitment, without living the way of Christ. I suspect the same is true here of Cain, that he was, at his core, resolutely opposed to all things righteous, that he was aligned with the evil one, that he is the archetype and father of those whom St. Paul describes in Romans 1, those who although they knew God, did not honor him as God or give thanks to him but became futile in their thinking and darkened in their hearts (see Rom 1:18 ff). And when evil is shone as evil by the presence of righteousness, evil strikes back to destroy the good.

So, St. John writes, we should not be surprised when the same happens to us, when the world hates us. And, again, in the short term, it may look like the world is winning the conflict between evil and righteousness. But that is a myopic view, a near-sighted distortion of the truth. It is the righteous who have passed through death, passed out of death, into life. St. John writes this: We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death (1 John 3:14). Our love for one another is the evidence that we are not like Cain: of the evil one and thus subject to death. Hate is evidence of death; love is evidence of life.

But, what kind of love is St. John writing about? What does it mean to love the brothers? — and when both St. John and I say “brothers” we mean “brothers and sisters.” St. John points to Jesus as the example:

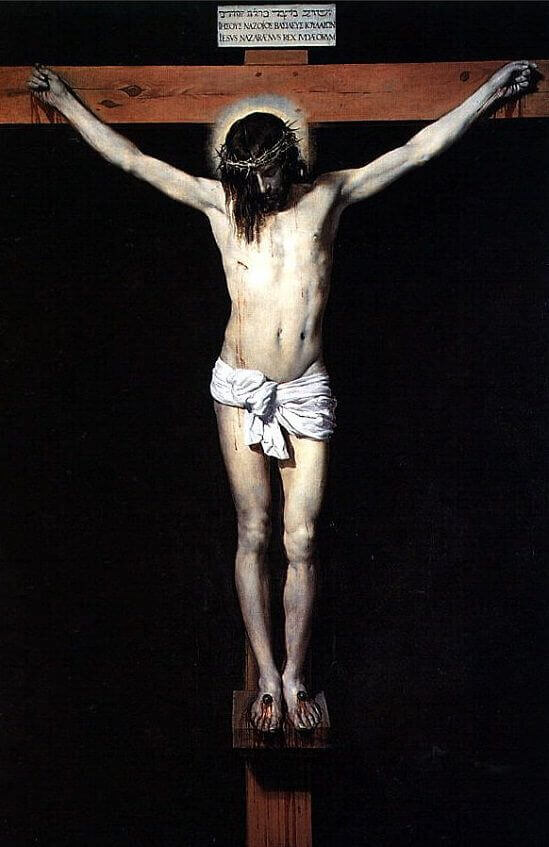

16 By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us, and we ought to lay down our lives for the brothers (1 John 3:16).

That is a high standard of love — laying down your life for someone. If we take that concretely, then none of us here have ever loved our brothers, and it is likely that none of us here will ever be called to do. So, St. John makes it clear that we lay down our lives not only only by dying physically, but rather by dying to self, by sacrificing for the good of the brothers:

17 But if anyone has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in him? 18 Little children, let us not love in word or talk but in deed and in truth (1 John 3:17-18).

This is very down to earth. If you see a brother who has a real and substantial need, and you have resources but refuse to help him, then you don’t have God’s love in you. You have not passed from death to life; you are still in darkness. Imagine a relatively affluent church having some poorer members who are routinely forced to choose between housing and medicine because they can’t afford both. If the church has the resources and chooses not to help, it would be hard to say that God’s love abides there. The heart of that church is hardened. Now, apply that to the individual members of the church, folk like you and me. If I can help a brother in true need and choose not to, then I am, at best, loving in word and talk, but not in truth. But, if I do help, that is the evidence that I love in truth. If I do help, that is reassurance before God that my heart is not closed.

This matter of the heart is crucial. There are many spiritual illnesses of the heart, illnesses that run the gamut from hardness of heart to excessive scrupulosity, from a refusal to open the heart in love at all to despair that whatever is done in love is never enough to please God. Those with the former illness — hardness of heart — feel no remorse for the good they could have and should have done but did not do, and the latter — those suffering from scrupulosity — feel guilt for the good they have done, that it is somehow not enough, never enough. God will prod the former and reassure the latter. Here is how St. John says it:

19 By this we shall know that we are of the truth and reassure our heart before him; 20 for whenever our heart condemns us, God is greater than our heart, and he knows everything. 21 Beloved, if our heart does not condemn us, we have confidence before God (1 John 3:19-21).

And, because as the prophet Jeremiah says, the heart is deceitful above all things, we pray with the Psalmist that God will reveal our hearts to us, lest we delude ourselves:

23 Search me, O God, and know my heart;

try me and examine my thoughts.

24 Look well if there be any way of wickedness in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting (Ps 139:23-24, BCP 2019, p. 456).

St. John says that, if our hearts are pure, if we are keeping God’s commandments and doing what pleases him, then God will honor our prayers and give us what we ask for:

22 and whatever we ask we receive from him, because we keep his commandments and do what pleases him. 23 And this is his commandment, that we believe in the name of his Son Jesus Christ and love one another, just as he has commanded us. 24 Whoever keeps his commandments abides in God, and God in him. And by this we know that he abides in us, by the Spirit whom he has given us (1 John 3:22-24).

This is not a blank check, not least because our hearts are not wholly pure and because we do not perfectly follow the commandments to love God with all our heart and soul and mind and to love our neighbor — and our brother — as ourselves. For me this promise is aspirational. The more I purify my heart — the Lord being my helper — and the more I love in deed and not in word only, the more my heart and mind will be aligned with God’s will, so that what I ask of him will be pleasing to him and granted by him. The key is the commandment he has given us: to believe in the name of his Son Jesus Christ and to love one another, just as he has commanded us.

I close with a word from Tertullian, a second and third century Christian apologist who offered a description of early Christian worship and life. After discussing many characteristics that set Christians apart from the surrounding culture, he closes with this:

But it is mainly the deeds of a love so noble that lead many to put a brand upon us. See, they say, how they love one another, for they themselves are animated by mutual hatred. See, they say about us, how they are ready even to die for one another (Tertullian, Apology, Chapter XXXIX).

Please God, may that be said of the Church in this and every age. Amen.