Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

Anglican Chant Workshop: Session 1 — Introduction to Chant and Basic Tones

Collect for Church Musicians and Artists

O God, whom saints and angels delight to worship in heaven: Be ever present with your servants on earth who seek through art and music to perfect the praises of your people. Grant them even now true glimpses of your beauty, and make them worthy at length to behold it unveiled for evermore; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Introduction

I’ve titled this class Anglican Chant Workshop for a particular reason. A workshop is a place you go first to learn how to do something and then to hone your skill and create things. And that is the purpose of this class: to show you how to do something, to give you a place to practice together, and then to leave here and create. By the end of the course, you should be able to open the Book of Common Prayer 2019 (BCP 2019) to any Psalm or Canticle and be able, with just a little preparation, to chant the text using one or more styles of chant. Those who are industrious, can learn to do this with just a Bible. But, I encourage you — for a host of reasons — to get the BCP 2019. It will make chanting much easier, not to mention that it is a treasury of prayer and liturgy which repays its study and regular use many fold.

Lift Every Voice

Under Friday night lights, in countless high school football stadiums across the country this fall, people of all ages and backgrounds will stand — many with hand over heart — and sing the National Anthem.

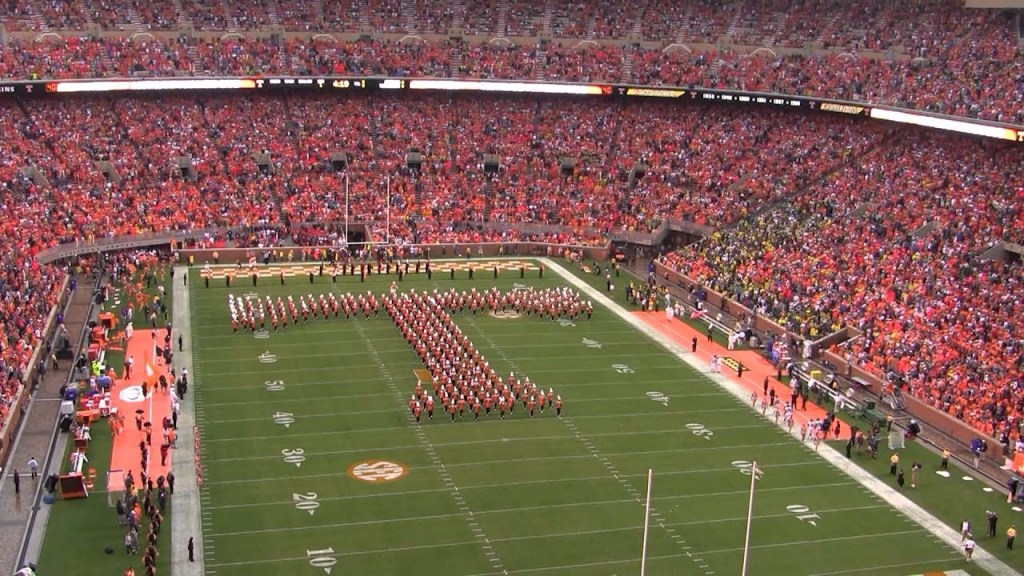

In Tennessee, on home game Saturdays, around tailgates, in front of televisions and radios, and gathered in Neyland Stadium, faithful and fervent Vols-for-Life will rise and sing the alternate national anthem, Rocky Top, to the strains of the Pride of the Southland Band.

In bars, at parties, and in family rooms people will embarrass themselves — all in good fun, of course — with round after round of karaoke by filling in the missing voice on favorite songs, singing with abandon.

In the privacy of showers and cars, in small gatherings of friends around the campfire, amidst massed crowds of strangers at Beyoncé and Taylor Swift concerts, people sing.

And, more than anywhere else, people gathered in worship at churches of every theological and denominational stripe sing: a capella; accompanied by guitars and drums, by piano and organ; in ancient hymnody and modern praise choruses; in unison and in four part harmony; in known languages and even in tongues; with theological precision and with devotional poetry; in praise and lament, in faith and doubt, in tune and out of tune. God’s people sing.

And that raises questions.

Why? Why do we sing?

We sing for the same reason we bring out the china and crystal and the sterling silver — or at least the “good” dishes and the matching forks — for special occasions. The meal might taste the same served on paper plates and eaten with plastic forks, but the experience would be different. The china and silver signify that something special, something of great worth is happening and we experience it differently. We honor others with our best and we honor the one who has prepared the feast. It is similar with singing. We could all gather and recite texts together; and sometimes we do. But, when the texts have been written in poetry, we know they are special. When that poetry is set to music, they are more special still. In worship, we honor the truth when we sing it; more importantly, we honor the one who is the Truth. Singing is bringing out the good verbal china, marking such occasions as special.

We sing because singing fosters community. We sing by ourselves, yes, but we are more likely to sing with others, to sing what we have in common. Singing both identifies our community and creates it. Think of teaching a child Rocky Top. That song, and singing that song, inducts him/her into the community of Vols fans — it creates community by adding new members — and it identifies him/her as part of that community as distinct from Alabama or Georgia or Florida fans: Lord, have mercy on them.

We sing to express and to kindle our emotions. Some songs bring us to tears and help us express deep sorrow and lament. Other songs help us to process strong emotions like anger and to move through and beyond them. There are songs that help us celebrate, to rejoice, and there are songs that fill our hearts with love and devotion. In his commentary on Psalm 73, St. Augustine wrote:

For he who sings praise, not only praises,

but also praises with gladness;

he who sings praise, not only sings,

but also loves him of whom he sings.

In praise there is the speaking forth of one who is confessing;

in singing, the affection of one who loves.

We sing to strengthen our faith and our will. The first chant I learned — years ago now — was the Φως Ίλαρόν, O Gladsome Light, which we use in Evening Prayer:

O gladsome light,

pure brightness of the everliving Father in heaven,*

O Jesus Christ, holy and blessed!

Now as we come to the setting of the sun,

and our eyes behold the vesper light,*

we sing your praises, O God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

You are worthy at all times to be praised by happy voices,*

O Son of God, O Giver of Life,

and to be glorified through all the worlds (BCP 2019, p. 44).

Church tradition says that this hymn was composed in the early centuries of the Church by St. Athenogenes while on his way toward martyrdom. Can you imagine him singing the hymn as his executioners bound him to the stake and then lit the pyre, as the flames rose about him? I think about that as I chant the hymn and it strengthens my faith and my will.

On another personal note, Clare and I attended a Kirkin’ o’ the Tartans service many years ago at a large Episcopal church. That is a celebration of Scottish heritage when the tartans of the various clans are brought into church to be blessed. We were sitting in one of the transepts, so some of the “action” took place out of sight in the back of the nave. But, I distinctly remember the beginning of the service; I didn’t see it, but I heard it. First the drums started. Then came the sound of a thousand cats coughing up hair balls as bagpipes filled with air and came up to pitch. And then the march: drum and pipes at full volume echoing through the nave, bouncing off stone, filling the entire space with the most martial music I have ever heard. After a couple of minutes of it, I turned to Clare and said, “I just want to kill something!” The drums and pipes stirred the blood. It is no wonder that until 1996, the British government classified the bagpipes as weapons of war. Music, whether pipes or singing, can straighten the spine and strengthen the will.

We sing to learn texts. The older I’ve gotten, the worse my memory has grown; my capacity to memorize new material has certainly diminished. But, I find I can remember texts that are chanted or sung. There are several Psalms and Canticles that I would struggle to recite, but which I can chant without any difficulty. Singing activates a different portion of the brain than mere spoken language. We see this in nursing homes. Some residents are uncommunicative. But, start singing one of the old hymns and they join right in without missing a word.

Singing and Worship in Scripture

And we sing, in no small part, because it seems to be an inherent part of being human. It is no wonder, then, that singing is central to the most fundamental human drive and act of worship. Scripture is replete with examples of singing and with exhortations and instructions to sing. Let’s consider just a few.

Job 38:7

Rev 5:9-10

Ex 15

Judges 5 (especially vss 1-3, though the whole of the chapter is a song of praise)

1 Sam 18:7

2 Sam 1:17-27 (likely a song of lament though not specifically identified as such)

Psalms (consider especially Ps 95 and Ps 100 as used in Morning Prayer)

Acts 16:25 (cf Phil 2:5-11, the Carmen Cristi (Hymn to Christ))

Eph 5:15-20

Col 3:16

James 5:13

So, as this brief survey shows, there can be no doubt that singing is a God-given and God-ordained part of worship. If we are to be faithful to the biblical pattern of worship, we will sing.

Singing: Hymnody and Chant

In worship, two types of singing are most prevalent, at least historically: hymnody and chant. We might add praise and worship music as a third category, but some of it is very much like hymnody and some of it is very like chant. So, I will not consider it as a separate musical form. Let’s consider some of the differences between hymnody and chant, using Psalm 100 as an example. Let’s begin with hymnody.

First Version (L.M. Use Old One Hundredth)

1 All people that on earth do dwell,

Sing to the Lord with cheerful voice.

2 Him serve with mirth, his praise forth tell,

Come ye before him and rejoice.

3 Know that the Lord is God indeed;

Without our aid he did us make:

We are his flock, he doth us feed,

And for his sheep he doth us take.

4 O enter then his gates with praise,

Approach with joy his courts unto:

Praise, laud, and bless his name always,

For it is seemly so to do.

5 For why? the Lord our God is good,

His mercy is for ever sure;

His truth at all times firmly stood,

And shall from age to age endure.

What do you notice about the lyrics to this hymn? You might notice that the lyrics differ from the biblical text of the Psalm; they are an interpretation, a paraphrase, of the text, but not the text itself. Why is that true? Well, count the syllables in each line of the hymn. Do you notice that each line has eight syllables and each verse has four lines. We say that the hymn has meter or is metrical. This is, it has a fixed rhythmic structure: 8.8.8.8 which is called long meter. The text of Psalm 100 had to be altered to fit the meter of the hymn. Do you notice also that the Hebrew poetry of the Psalm, which does not rhyme, has been rendered into a Western poetic form which does rhyme? The hymn has the ABAB rhyme scheme in which odd lines rhyme and even lines rhyme within each stanza. Oftentimes, hymns alter the Biblical text for the sake of both meter and rhyme.

There are other metrical and rhyming possibilities for this Psalm.

Second Version (C.M. Use Amazing Grace)

1 O all ye lands, unto the Lord

make ye a joyful noise.

2 Serve God with gladness, him before

come with a singing voice.

3 Know ye the Lord that he is God;

not we, but he us made:

We are his people, and the sheep

within his pasture fed.

4 Enter his gates and courts with praise,

to thank him go ye thither:

To him express your thankfulness,

and bless his name together.

5 Because the Lord our God is good,

his mercy faileth never;

And to all generations

his truth endureth ever.

Notice three things: the words are different yet again, the meter is now 8.6.8.6 which is called common meter, and the rhyme scheme is now ABCB. So, when arranging the Psalm or other biblical texts for hymnody, there is typically some loss of fidelity to the actual text. That is simply because these texts developed independently of Western metrical music and must be adapted to fit the rhythms and rhymes of hymnody.

In contrast to this, liturgical chant was created to provide a musical expression that is wholly faithful to the text; the text always comes first in chant, and the music fits itself to the word. As an example, consider a simple Gregorian Chant of Psalm 100 with the text taken from the Book of Common Prayer. Note that you could also take the text directly from any translation of the Scripture, even from the Hebrew — if you knew it — or from the Greek in the case of a New Testament text. The same chant would apply in every case.

PSALM 100

1 O be joyful in the Lᴏʀᴅ, all you ‘lands; *

serve the Lᴏʀᴅ with gladness, and come before his presence with a ‘song.

2 Be assured that the Lᴏʀᴅ, he is ‘God; *

it is he that has made us, and not we ourselves; we are his people, and the sheep of his ‘pasture.

3 O go your way into his gates with thanksgiving, and into his courts with ‘praise; *

be thankful unto him, and speak good of his ‘Name.

4 For the Lᴏʀᴅ is gracious, his mercy is ever’lasting, *

and his truth endures from generation to gener’ation.

Now, there are other forms of chant, but they all preserve the integrity of the text. Let’s consider an example of Simplified Anglican Chant for this same Psalm. I invite you to chant along with me if you know the tone.

Any of these chant tones — Gregorian or Simplified Anglican — could be used with any text — directly — without changing/adapting the text. That is part of the beauty of chant; it is a musical form created to support and express the biblical text. The word is always primary.

There are certainly other differences between hymnody and chant, but that is the one I wanted to highlight: the development of a musical form — chant — specifically to support and express the text as-is, and which can be used on a variety of texts.

Types of Chant

I have mentioned two different types of chant already: Gregorian and Simplified Anglican Chant. Since this course is an introduction — Chant 101, so to speak — I want it to be as simple and useful as possible; for that reason, we will focus on Simplified Anglican Chant. It is not so much that Gregorian Chant — in modern musical notation — is difficult, but rather that it requires more preparation for each text and a bit more musical ability. But, with just a bit of practice and experience, Simplified Anglican Chant can be sung “on the fly:” select a text, select a tone, and chant. Simplified Anglican Chant is also what we use at Apostles for chanting the Psalms in the early service, so many of you will already be somewhat familiar with it.

Just for a bit of background, Gregorian Chant, or Western plainchant, is monophonic (a single melody line sung without harmonization) and sung unaccompanied (a cappella). Tradition credits Pope St. Gregory the Great (c. 540-604) with the creation of this form; it is more likely that he collected, systematized, and institutionalized existing chant forms and made them the norm for Western liturgical music. Anglican Chant emerged significantly later, in the 19th century. It is polyphonic (generally with four part harmony) and is typically accompanied. It is less complex than Gregorian Chant, but still requires considerable preparation and practice. It is often used by Anglican choirs.

But, for “ordinary” folk like you and me, there is a less complicated version of Anglican Chant called Simplified Anglican Chant, created by Robert Knox Kennedy in the 20th century. While it is polyphonic, it may be sung in unison, either accompanied or a cappella.

Basic Chant

Before we get to Simplified Anglican Chant, there are even more basic chant forms that work perfectly well. The simplest form of chant is monotone, where the entire text is chanted to a single note. This is typically the way the Lord’s Prayer is chanted on Sundays and Holy Days in the Daily Office. Let’s chant the Our Father together. I will establish the pitch with the invocation “Our Father,” and then you join the prayer.

Our Father, who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy Name,

thy kingdom come,

thy will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

and the power, and the glory,

for ever and ever. Amen.

Monotone is a wonderful introduction to chant and may well be all that some people ever want or need. But, for others, monotone becomes…well, monotonous if used exclusively. So, let’s look at a slight variation, what we might call Step Up, Step Down chant. We need a text. Any Psalm will do; I’ve chosen Psalm 131 because it is beautiful, short, and illustrative of several concepts. All Psalm texts are taken from the BCP 2019, The New Coverdale Psalter.

PSALM 131

1 O Lᴏʀᴅ, I am not haughty; *

I have no proud looks.

2 I do not occupy myself with great matters, *

or with things that are too high for me.

3 But I have stilled and quieted my soul, like a weaned child upon his mother’s breast; *

so is my soul quieted within me.

4 O Israel, trust in the Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for evermore.

First, let’s consider the format of the Psalm. Notice that it is divided into verses, and further that each verse is divided into half-verses, indicated by the asterisk. If you simply open to the Psalms in your Bible, you will have one of those divisions — verses — but not the other — half-verses. The division into half-verses that you will find in Psalters — the book of Psalms — is primarily for the use of Psalms in worship, to enable the people to say or chant the Psalms together easily. So, for example, when we pray Morning, Midday, and Evening Prayer at church, the officiant will say: We will now say Psalm XX in unison, or responsively by whole verse, or responsively by half-verse. In this way, everyone know what part of the Psalm is his/her responsibility.

In Step Up, Step Down chant, we change musical pitch at the end of each half-verse: step up at the end of the first half-verse and step back down at the end of the second half-verse. That is the basic idea, though there are some subtleties. Each verse is its own musical entity, and we start again with each verse.

Let me illustrate this with the first verse of Psalm 131.

1 O Lᴏʀᴅ, I am not haughty; *

I have no proud looks.

Simple enough? Step up at the end of the first half-verse; step down at the end of the second half-verse, and start all over again with the next verse. If you are doing this by yourself, you can’t go wrong. But, if we are chanting a Psalm together, we must agree on where to change pitch. We will change pitch at the end of each half-verse, but that doesn’t necessarily mean at the beginning of the last word in the half-verse. To see what I mean, let’s consider verse 4.

4 O Israel, trust in the Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for evermore.

The change in the first half-verse is obvious, isn’t it?

O Israel, trust in the ‘Lᴏʀᴅ *

But, what about the second half-verse? If we change pitch at the beginning of the last word in the line, it would sound like this.

4b from this time forth for ‘evermore.

That sounds a bit off, a bit awkward, doesn’t it. That’s because it is not how we would say the line; it puts the ac-cent’ on the wrong syl-lable’. It should be ever-more’ and not ever’-more. And this leads to an important principle in Anglican Chant; we chant the Psalm as we would read it aloud, changing pitch at points of emphasis in the last word or phrase in each half-verse. So, let’s say verse 4 together, noticing where we naturally put the emphasis at the end of each half-verse. Notice also that, even though English is not primarily a tonal language with pitch change indicating the meaning of words, it does retain some tonality for emphasis and at the end of units of speech. There is often a rising pitch for questions and a falling pitch for declarative statements. If you pay attention to how you read aloud, you will notice that in this Psalm verse.

4 O Israel, trust in the ‘Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for ever’more.

Now, we can do the Step Up, Step Down chant of this verse, confident of where to change pitch. Let’s try it.

4 O Israel, trust in the ‘Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for ever’more.

We can now take the text of the entire Psalm and mark it to show the pitch changes. That is called pointing the Psalm, and the result is called a pointed Psalm. There are many ways to do this, some elaborate and some very simple. At Apostles, we simply use apostrophes to note the pitch changes, as you have noticed in the first service bulletin.

So, let’s take the whole of Psalm 131 and point it.

1 O Lᴏʀᴅ, I am not haughty; *

I have no proud looks.

2 I do not occupy myself with great matters, *

or with things that are too high for me.

3 But I have stilled and quieted my soul, like a weaned child upon his mother’s breast; *

so is my soul quieted within me.

4 O Israel, trust in the Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for evermore.

Verse 1 is straightforward.

1 O Lᴏʀᴅ, I am not ‘haughty; *

I have no proud ‘looks.

Verse 2 is a little more complicated. Read it aloud to yourself and notice where you put the emphasis or the verbal tone change at the end of each half-verse. Then, discuss it with those around you to see if you all agree.

I suspect the first half-verse was easy, with the emphasis —and pitch change — falling on the first syllable of “matters.” But, there might have been some disagreement on the second half-verse. I can argue for two different emphases:

Option 1: or with things that are too high for ‘me.

Option 2: or with things that are too ‘high for me.

Each option is possible. There isn’t a right or wrong; we just have to make a decision and agree if we are going to chant this Psalm together. I point the Psalm for service each week, so I am the one making the decision for Apostles. When I pointed the Psalm, I went with Option 2: or with things that are too ‘high for me. That is how I normally accent the Psalm when reading it, so I chose to emphasize it the same way in chant. The emphasis on “high” also picks up the text’s theme of “proud looks” and “great matters” previously in the Psalm.

Now, let’s complete the pointing with the last two verses. Again, read the verses aloud and note where the emphases fall. Here is the way I pointed it.

3 But I have stilled and quieted my soul,

like a weaned child upon his mother’s ‘breast; *

so is my soul quieted with’in me.

4 O Israel, trust in the ‘Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for ever’more.

Now, we have the entire chant pointed. Let’s try the Step Up, Step Down chant tone with the pointed Psalm. We will also add the Gloria. [Handout 2]

1 O Lᴏʀᴅ, I am not ‘haughty; *

I have no proud ‘looks.

2 I do not occupy myself with great ‘matters, *

or with things that are too ‘high for me.

3 But I have stilled and quieted my soul,

like a weaned child upon his mother’s ‘breast; *

so is my soul quieted with’in me.

4 O Israel, trust in the ‘Lᴏʀᴅ *

from this time forth for ever’more.

Glory be to the Father, and to the ‘Son,*

and to the Holy ‘Spirit:

as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever ‘shall be,*

world without end. A’men.

Again, you may be quite content with this method of chant, at least for awhile. But, many of you will want to move along to Simplified Anglican Chant and perhaps even take the plunge into Gregorian Chant. We’ll explore more of that in our next session.

Homework

For homework, I would like you to point Psalm 121 and practice chanting it with Step Up, Step Down chant.

PSALM 121

1 I will lift up my eyes unto the hills; *

from whence comes my help?

2 My help comes from the Lᴏʀᴅ, *

who has made heaven and earth.

3 He will not let your foot be moved, *

and he who keeps you will not sleep.

4 Behold, he who keeps Israel *

shall neither slumber nor sleep.

5 The Lᴏʀᴅ himself is your keeper; *

the Lᴏʀᴅ is your defense upon your right hand,

6 So that the sun shall not burn you by day, *

neither the moon by night.

7 The Lᴏʀᴅ shall preserve you from all evil; *

indeed, it is he who shall keep your soul.

8 The Lᴏʀᴅ shall preserve your going out and your coming in, *

from this time forth for evermore.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son,*

and to the Holy Spirit:

as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be,*

world without end. Amen.

You might also begin pointing and chanting the Psalms for Morning and Evening Prayer this week. It is not only good practice, but good worship.