Session 6: Discerning the Movement of the Spirit

Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

The Theology of the Holy Spirit

Session 6: Discerning the Movement of the Holy Spirit

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

O God the Father, Creator of heaven and earth,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Son, Redeemer of the world,

Have mercy upon us.

O God the Holy Spirit, Sanctifier of the faithful,

Have mercy upon us.

O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, one God,

Have mercy upon us (The Great Litany, BCP 2019, p. 91).

Introduction

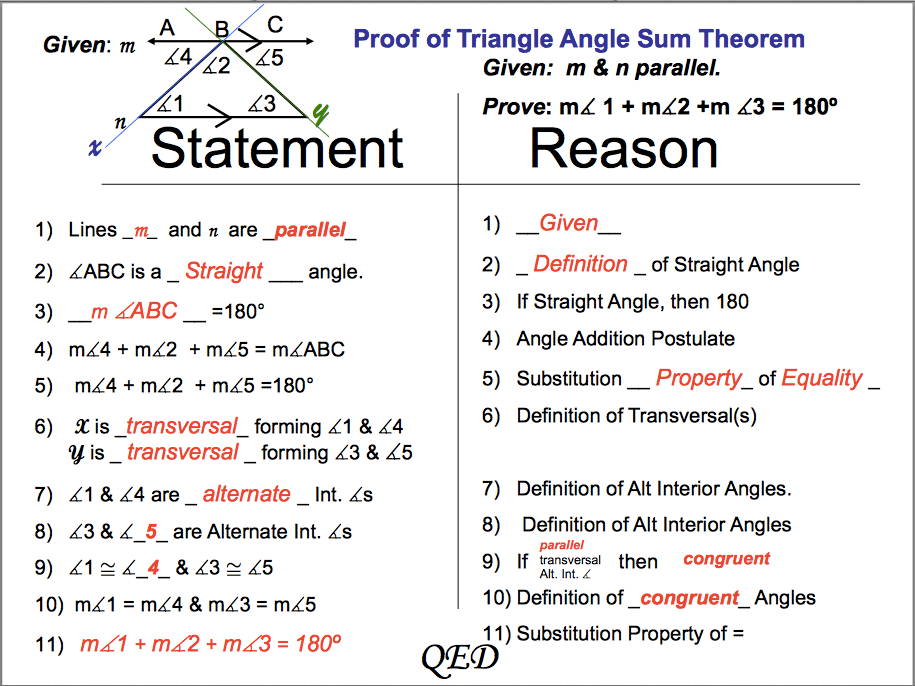

Sometimes in presenting ideas it is best to go from small to large, from the very specific to the very general. That is most often the way a mathematical proof is presented. Start small with a few definitions, a few axioms, and work your way upward to a larger, more general theorem. Alternately, we might start with large and general notions and work our way downward toward the specific implications of the larger idea. That might be the way one would present the vision statement for an organization, for example. Start with the large scale, guiding principles and goals for the organization, and then work your way downward to what that means for each each division, each unit, each individual in the organization — from general down to granular.

It is that latter approach — from large and general to small and specific — that we have pursued in this course on The Theology of the Holy Spirit. We began with the very general notion of epistemology, of how we know what we know about the Holy Spirit. And, we noticed in Scripture — not least in the Acts of the Apostles — a process: experience, spiritual/cognitive dissonance, Scripture, Sacraments, Church all leading to a right understanding of that initial experience. Next, we considered the Holy Spirit in the three Creeds of the Western Church: the Nicene Creed, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Athanasian Creed. We saw how they defined the nature and work of the Holy Spirit, one of the divine persons of the triune God. Then, we turned our attention to the agency of the Holy Spirit in the Sacramental life of the Church and the Christian, from new birth in baptism, through every stage in the life of the believer, and pointing onward to eternal union with Christ. In the fourth lesson we began to consider how it is possible to grow in the Spirit, to increase our awareness of and participation with what the Spirit is doing — how to kindle and to avoid quenching the Spirit. Last week we looked at the evidence of the Spirit in our corporate and individual lives as we examined the fruit and gifts of the Spirit. Today we will become still more specific, as we look for ways to become more aware of the movement of the Holy Spirit in our individual lives.

Discerning the Movement of the Holy Spirit

Any course on the Holy Spirit should come back again and again to the book of Acts in which the Holy Spirit is the lead actor and everyone else is in the supporting cast. So, we start there today with a scene near the beginning of St. Paul’s second missionary journey in Acts 16. Paul and Silas set out to visit and strengthen the churches that Paul and Barnabas had established on their earlier mission. At Lystra they add Timothy to their team. And then we get this somewhat strange word about the trio:

6 And they went through the region of Phrygia and Galatia, having been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to speak the word in Asia. 7 And when they had come up to Mysia, they attempted to go into Bithynia, but the Spirit of Jesus did not allow them. 8 So, passing by Mysia, they went down to Troas. 9 And a vision appeared to Paul in the night: a man of Macedonia was standing there, urging him and saying, “Come over to Macedonia and help us.” 10 And when Paul had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go on into Macedonia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them (Acts 16:6-10).

Apparently, Paul had intended to travel throughout Asia, but the Holy Spirit forbade him. How? I wonder. Then Paul says, “Well, if not Asia, we’ll go to Bithynia.” But, once again, the Holy Spirit — identified here as the Spirit of Jesus — says no. Again, how that was communicated to Paul is not told us. But then, sometime later, during the night, Paul sees a vision of a man of Macedonia beckoning Paul and the team to come there; given the prominence of the Holy Spirit throughout the account, I assume the vision was prompted by the Spirit. Paul took this as a sign that a European mission was the will of God.

So, we see in this brief text the Holy Spirit working to direct St. Paul’s ministry in ways we know and in ways we don’t. That is true throughout Acts; we see the Holy Spirit revealing God’s will to various people in various ways: through the casting of lots, something equivalent to flipping a coin or drawing straws (Act 1:15 ff); through an act akin to teleportation (Acts 8:39-40); through repeated visions and direct words (Acts 10:17-20); in council with church leaders through their sharing stories and searching the Scriptures (Acts 15:1-29); through the words of “ordinary” disciples speaking prophetically (Acts 21:1-4).

This is the witness of Scripture: that the Holy Spirit reveals the will of God to God’s people, directs their actions, informs their understanding. That was clearly the case in the Apostolic era, and we believe it to be true also today, true throughout the history and the future of the Church. That conviction is expressed in many of our prayers, not least in this collect for guidance:

Collect for Guidance

O God, by whom the meek are guided in judgment, and light rises up in darkness for the godly: Grant us, in all our doubts and uncertainties, the grace to ask what you would have us do, that the Spirit of wisdom may save us from all false choices; that in your light we may see light, and in your straight path we may not stumble; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (BCP 2019, p. 669).

So the question seems to be not whether the Holy Spirit is actively revealing God’s will to us — collectively and individually — but rather how he is doing so. Where do we look to find the Holy Spirit and how do we properly discern his guidance? And, given the human penchant for delusion, how do we distinguish the voice of the Holy Spirit from our own voices? These are some of the questions that we’ll consider in this final session on The Theology of the Holy Spirit.

I will draw heavily on the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), the Spanish theologian and founder of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). St. Ignatius devoted the greater part of his thinking to matters of discernment, of noticing and listening to the movements of the Holy Spirit. Throughout his life he worked to formulate and document this spirituality in a program of spiritual direction known now as “The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius.” That is the work that I will draw from.

First Principle and Foundation: A Spiritual Audio Equalizer

You are familiar with audio equalizers? They allow you to adjust certain frequency ranges in the music you are listening to in order to customize your listening experience: a little more bass, normal midrange, a little upper end boost. They can especially help those of us who are “getting” older as we lose the ability to hear certain frequencies as well, particularly high frequencies. I hear bass well, but the treble is a bit diminished. I may need to turn one frequency down and boost the other if I am to hear the music rightly.

There is a spiritual analogy here. We have many “voices” speaking to us, vying for our attention and our obedience. Out of all these voices, it is the Holy Spirit’s that we want to hear distinctly. We want to boost that one and turn down the others. Some we will be able to turn down and others we’ll simply have to recognize as distortions and learn to disregard. The main voice that I need to turn down is my own, my own set of desires and hopes and expectations and fears and doubts clamoring incessantly in my head and demanding my attention and my action. I need a spiritual audio equalizer to tune that out. That is what St. Ignatius provides us in his First Principle and Foundation:

Man is created to praise, reverence, and serve God our Lord, and by this means to save his soul.

The other things on the face of the earth are created for man to help him in attaining the end for which he is created.

Hence, man is to make use of them in as far as they help him in the attainment of this end, and he must rid himself of them in as far as they prove a hindrance to him.

Therefore, we must make ourselves indifferent to all created things, as far as we are allowed free choice and are not under any prohibition. Consequently, as far as we are concerned, we should not prefer health to sickness, riches to poverty, honor to dishonor, a long life to a short life. The same holds true for all other things.

Our one desire and choice should be what is more conducive to the end for which we are created (St. Ignatius of Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius (Louis J. Puhl, trans.), Loyola Press (1951), p. 12, hereafter The Exercises).

This principle tells us who we are (creatures, not the creator), what we are made for (to praise, reverence, and serve God), what all other things are here for (to help us fulfill our purpose), and how we must use them or let them alone (only for the attainment of our purpose). All of this is foundational. Then, St. Ignatius states the principle that turns down and filters out the voice of our disordered desires so that we can listen to the Holy Spirit:

Therefore, we must make ourselves indifferent to all created things, as far as we are allowed free choice and are not under any prohibition. Consequently, as far as we are concerned, we should not prefer health to sickness, riches to poverty, honor to dishonor, a long life to a short life. The same holds true for all other things.

Holy Indifference is the spiritual equalizer we need if we are to hear distinctly the voice of the Holy Spirit. I must filter out my preferences and turn up and focus on that for which I was made: to love, praise, and worship the Lord and to be obedient to his will. That is not as easy as using a few slider bars on a digital audio app. It requires a lifetime of discipline: prayer, worship, Scripture, sacraments, confession, participation in the life of the Church, renewing of the mind and heart. But, it does provide us a test in any given moment of discernment, really a prerequisite for any true discernment: Am I indifferent? Do I want only the will of God? Am I committed to fulfilling the purpose for which I am created? Am I listening to myself, or to the Holy Spirit? I find this First Principle and Foundation a necessary reminder in moments of discernment, in moments when I am not certain I am listening clearly to the Holy Spirit.

Listen To Your Life

We’ve spoken so far of listening clearly, of picking out the Holy Spirit’s voice from among all the other voice vying for our attention. The next matter to consider is this: What are we listening to? Where do we expect to hear the voice of the Holy Spirit?

When we think of listening to or looking for the guidance of the Holy Spirit, where are some places we normally turn? Scripture, prayer, liturgy, sacraments, the teaching of the Church, the council of the saints past and present: all of these are places and ways in which the Holy Spirit speaks to us. But, all of these speak to us in the midst of, in the context of our own lives. It is in the midst of our lives that we read Scripture, pray, participate in liturgy, receive the sacraments, listen to the teachings of Church and Creeds and Councils. When we listen for the Holy Spirit, we must listen to our lives.

Frederick Buechner — of blessed memory — novelist, memoirist, sometimes teacher and preacher, wrote compellingly about the need to listen to our lives. You do not have to agree with every detail of his writing to know it generally to be true.

Listen:

If God speaks anywhere, it is into our personal lives that he speaks. Someone we love dies, say. Some unforeseen act of kindness or cruelty touches the heart or makes the blood run cold. We fail a friend, or a friend fails us, and we are appalled at the capacity we all of us have for estranging the very people in our lives we need the most. Or maybe nothing extraordinary happens at all — just one day following another, helter-skelter, in the manner of days. We sleep and dream. We wake. We work. We remember and forget. We have fun and are depressed. And into the thick of it, or out of the thick of it, at moments of even the most humdrum of our days, God speaks. But what do I mean by saying that God speaks?

He speaks not just through the sounds we hear, of course, but through events in all their complexity and variety, through the harmonies and disharmonies and counterpoint of all that happens…. To try to express in even the most insightful and theologically sophisticated terms the meaning of what God speaks through the events of our lives is as precarious a business as to try to express the meaning of the sound of rain on the roof or the spectacle of the setting sun. But I choose to believe that he speaks nonetheless, and the reason that his words are impossible to capture in human language is of course that they are ultimately always incarnate words. They are words fleshed out in the everydayness no less than in the crises of our own experience (from Frederick Buechner, The Sacred Journey and Listening to Your Life).

Buechner starts with a conditional statement, an if-then bit of logic: if God speaks anywhere, then it is into our personal lives that he speaks. We might want to hedge that around with all kinds of clarifications and nuance, and that is as it should be. But really he is saying no more than the obvious; if the Holy Spirit is going to speak to me, if must be in the context of — in the midst of and through — the events of my life: events including prayer, worship and the reading of Scripture; the cooking of meals and the doing of dishes; the serving of others and the being served by them; my sin and repentance and absolution; the moments of joy and despair and routine. All of it: God is speaking in all of it, in all the moments of our lives. And he is speaking through the moments of our lives as the medium/mode of communication. A painter uses color and perspective to speak truth. A dancer uses movement and form to express meaning. God uses human lives to reveal himself. That is why Scripture is primarily a narrative, a story of God revealing himself in and through a people, in and through the lives of men and women and families and tribes and nations and the church. Buechner is saying that what is true in Scripture — God revealing himself to and through people in the context of their lives — is still true; God is revealing himself in and through the mess and muddle and glory of your life and of mine, not just in the extraordinary moments, but in the everydayness of it.

What should our response be to that, to the fact that the Holy Spirit is speaking? Buechner suggests this:

Listen to your life. All moments are key moments. I discovered that if you really keep your eye peeled to it and your ears open, if you really pay attention to it, even such a limited and limiting life as the one I was living on Rupert Mountain opened up onto extraordinary vistas. Taking your children to school and kissing your wife goodbye. Eating lunch with a friend. Trying to do a decent day’s work. Hearing the rain patter against the window. There is no event so commonplace but that God is present within it, always hiddenly, always leaving you room to recognize him or not to recognize him, but all the more fascinatingly because of that, all the more compellingly and hauntingly….If I were called upon to state in a few words the essence of everything I was trying to say both as a novelist and as a preacher, it would be something like this: Listen to your life. See it for the fathomless mystery that it is. In the boredom and pain of it no less than in the excitement and gladness: touch, taste, smell your way to the holy and hidden heart of it because in the last analysis all moments are key moments, and life itself is grace (Frederick Buechner, from Now and Then and Listening to Your Life).

Listen to your life; listen to what the Holy Spirit is saying in and through your life. That may sound simple, but it is so easy to be so busy living life that we fail to take time to listen to it, to notice the Holy Spirit speaking in and through the ordinary — and sometimes the extraordinary — events of our lives. St. Ignatius of Loyola made this listening to life the non-negotiable center of his spirituality and that of the Jesuit order. He insisted that each Jesuit offer a Prayer of Examen each day — usually twice each day — a time of listening to the Holy Spirit through the events of the day. There are many ways of praying the Examen, but each is essentially a prayerful review of the events of the day with the help of the Holy Spirit, listening for and discerning the meaning of those events. What follows is the basic pattern.

Prayer of Examen

• Preparation: Take a moment to settle down, focus your attention on prayer, and ask the Holy Spirit to guide you in the following examen. This could be as simple as sitting briefly in silence, taking a few breaths, and praying: Come Holy Spirit, reveal the meaning of my day.

• Thanksgiving: Express your gratitude to God for the gift of the day, for the blessings of it (be specific), and perhaps even for the challenges of it (God was present there, too).

• Review: Review the events of the day. When/where were you aware of God’s presence and pleasure? Where were you unaware of God’s presence and pleasure? When did you follow God closely and when did you stray? Thank God for the former and ask forgiveness for the latter.

• Preview: Look ahead to the next day. Consider the opportunities and challenges it will offer, and ask the Holy Spirit to guide you through it and to help you be attentive to his presence it it.

• Closure: Take a moment to end the examen with silence or perhaps with a brief prayer.

This is simply an outline. If you think it might be a helpful part of your rule of prayer, experiment with it and adapt it. It is simply a tool to help you listen, with the Holy Spirit, to your life, to the way God reveals himself in and through the events of your life. Some of you may journal regularly. That, too, is a way of listening prayerfully to your life. The method is less important than the listening.

Consolation and Desolation

What do we listen for when we listen to our lives? There are many ways to answer that question, but St. Ignatius listened primarily for the voice of the Holy Spirit in the consolations and desolations that we experience. For Ignatius, consolation and desolation are spiritual terms and not merely emotional terms on the order of joy or sadness, peace or anxiety. Consolation and desolation point toward the movement of the Holy Spirit in one’s life, or toward the movement of the evil spirit. Let’s consider St. Ignatius’s definitions of these two states.

3. SPIRITUAL CONSOLATION. I call it consolation when an interior movement is aroused in the soul, by which it is inflamed with love of its Creator and Lord, and as a consequence, can love no creature on the face of the earth for its own sake, but only in the Creator of them all. It is likewise consolation when one sheds tears that move to the love of God, whether it be because of sorrow for sins, or because of the sufferings of Christ our Lord, or for any other reason that is immediately directed to the praise and service of God. Finally, I call consolation every increase of faith, hope, and love, and all interior joy that invites and attracts to what is heavenly and to the salvation of one’s soul by filling it with peace and quiet in its Creator and Lord (The Exercises, p. 142).

First, Ignatius notes that consolation is a movement aroused in the soul; it is not primarily a psychological or emotional state, though these may be attendant to consolation. The soul is involved when one is moved to — inflamed with — love for God. Let me offer an example of the difference between consolation and an emotional state. Imagine you are at the beach or in the mountains and you see a glorious sunset; you are moved deeply by its beauty.

If you stop there — just deeply moved by its beauty — it is likely that you are having an emotional experience, which is itself a grace from God; but, it is not what Ignatius means by consolation. Now, suppose, while viewing the sunset, you are drawn upward to the contemplation and praise of God the creator and of Jesus Christ the true light. Suppose you are moved to pray or sing the Phos Hilaron:

O gladsome light,

pure brightness of the everliving Father in heaven,

O Jesus Christ, holy and blessed!

Now as we come to the setting of the sun,

and our eyes behold the vesper light,

we sing your praises, O God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

You are worthy at all times to be praised by happy voices,

O Son of God, O Giver of Life,

and to be glorified through all the worlds (BCP 2019, p. 44).

That is consolation, because you are moved to love for God, because you are rejoicing in the beauty of creation not merely for its own sake, but for the sake of the Creator of all beauty. That is a movement of the Holy Spirit.

St. Ignatius also mentions tears as a sign of consolation. As before, this is not merely a matter of emotion. Instead, these tears are a movement of the Spirit that ends not with sadness or even catharsis, but instead with praise and service of God. Think of tears shed in confession, when sitting quietly in prayer, or when bearing some burden of a brother or sister in Christ. Tears are indicative of consolation when they are not an end in themselves, but when they lead to God.

Lastly, St. Ignatius calls consolation every movement of the Spirit that leads to an increase of faith, hope, and love. For me, this is the gold-standard litmus test of consolation: Am I moving toward greater faith, hope, and love? If so, I am being moved by the Holy Spirit.

It is in the time of consolation that you are being moved and directed by the Holy Spirit. So, we listen to our lives for moments such as those with confidence that the Holy Spirit was/is present and active.

Conversely, St. Ignatius defines spiritual desolation. As you listen to his definition, keep in mind that, as with spiritual consolation, this is not primarily an emotional or psychological state, but rather a spiritual condition.

4. SPIRITUAL DESOLATION. I call desolation what is entirely the opposite of what is described in the third rule, as darkness of soul, turmoil of spirit, inclination to what is low and earthly, restlessness rising from many disturbances and temptations which lead to want of faith, want of hope, want of love. The soul is wholly slothful, tepid, sad, and separated, as it were, from its Creator and Lord. For just as consolation is the opposite of desolation, so the thoughts that spring from consolation are the opposite of those that spring from desolation (ibid).

Just listen again to some of the key terms and phrases to get a feel for desolation.

Darkness of soul

Turmoil of spirit

Inclination to the low and earthly

Restlessness, disturbance, temptation

Want (lack) of faith, hope, and love

A slothful, tepid, sad soul which feels separated from it Creator

These characteristics are not normal sadness or clinical depression. This is a spiritual matter. The person experiencing spiritual desolation is operating not under the influence of the Holy Spirit but of the evil spirit. This is a battle for the welfare of one’s soul. As you listen to your life, pay attention to times of desolation. When did they come? What precipitated them? What ended them? We look for patterns so that we can battle the evil spirit effectively this time and in the times to come.

St. Ignatius instructs us to examine our lives — remember his emphasis on the Prayer of Examen — paying special attention to consolation as a movement of the Holy Spirit and desolation as a movement of the evil spirit. He emphasizes three aspects to this examination:

Awareness: Become aware when some spiritual movement is taking place in your soul, either of consolation or of desolation.

Understanding: Discern the meaning and direction of the movement. Is it from the Holy Spirit or from the evil spirit?

Action: Take proper action to accept and move with the Holy Spirit or to reject and move counter to the evil spirit.

St. Ignatius of Loyola: Rules for Discernment of Spirits

These definitions of consolation and desolation come from The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the third and fourth of his fourteen rules for discernment of spirits. We do not have time to consider the other rules in this class, but I do want you to have access to them, and I do recommend that you take time to prayerfully consider them. They provide great insight into the movement of the Holy Spirit — and of the evil spirit — in our lives, and they offer ways to respond appropriately to each movement. Fr. Timothy Gallagher is a noted authority in Ignatian spirituality, and I will provide you his simplified paraphrase of the rules of discernment. I will also add some comments of my own in italics.

Fr. Timothy Gallagher’s Paraphrase of the Ignatian Rules of Spiritual Discernment

Rules for becoming aware and understanding the different movements that are caused in the soul, the good ones, to receive them, and the bad ones, to reject them.

1. When a person lives a life of serious sin, the enemy fills the imagination with images of sensual pleasures; the good spirit stings and bites in the person’s conscience, God’s loving action, calling the person back. [A feeling of peace is not a reliable indication of a movement of the Holy Spirit. If a person is living in sin or moving toward sin, the opposite is true. The Holy Spirit will sting and bite the conscience of that person to lead him to repentance. It is the evil spirit who will bring a sense of peace to lure the unsuspecting person to destruction. Remember, there is a way that seems good to man, but its end is destruction.]

2. When a person tries to avoid sin and to love God, this reverses: now the enemy tries to bite, discourage, and sadden; the good spirit gives courage and strength, inspirations, easing the path forward. [Expect resistance from the evil spirit when you are progressing toward increasing faith, hope, love, and obedience.]

3. When your heart finds joy in God, a sense of God’s closeness and love, you are experiencing spiritual consolation. Open your heart to God’s gift!

4. When your heart is discouraged, you have little energy for spiritual things, and God feels far away, you are experiencing spiritual desolation. Resist and reject this tactic of enemy!

5. “In time of desolation, never make a change!” When you are in spiritual desolation, never change anything in your spiritual life. [This must be clarified. If you have made spiritual decisions in a time of consolation — when you were under the guidance of the Holy Spirit — never change those in a time of desolation. Suppose after prayerfully considering the matter, in a time of consolation you committed to praying Morning Prayer each day. Now, six months later, you are experiencing signs of spiritual desolation: slothfulness, a disinterest in spiritual things, etc. Now, you are tempted to stop praying Morning Prayer. This is where this most valuable rule “kicks in.” In a time of desolation — a time when, by definition, you are under the influence of the evil spirit — NEVER make a change to a commitment made in a previous time of consolation. Wait until the desolation is over, then reassess matters in a time of consolation.]

6. When you are in spiritual desolation, use these four means: prayer (ask God’s help!), meditation (think of Bible verses, truths about God’s faithful love, memories of God’s fidelity to you in the past), examination (ask – What am I feeling? How did this start?), and suitable penance (don’t just give in and immerse yourself in social media, music, movies . . ..). Stand your ground in suitable ways!

7. When you are in spiritual desolation, think of this truth: God is giving me all the grace I need to get safely through this desolation.

8. When you are in spiritual desolation, be patient, stay the course, and remember that consolation will return much sooner than the desolation is telling you.

9. Why does a God who loves us allow us to experience spiritual desolation? To help us see changes we need to make; to strengthen us in our resistance to desolation; and to help us not get complacent in the spiritual life.

10. When you are in spiritual consolation, remember that desolation will return at some point, and prepare for it.

11. The mature person of discernment: neither carelessly high in consolation nor despairingly low in desolation, but humble in consolation and trusting in desolation.

12. Resist the enemy’s temptations right at their very beginning. This is when it is easiest.

13. When you find burdens on your heart in your spiritual life, temptations, confusion, discouragement, find a wise, competent spiritual person, and talk about it.

14. Identify that area of your life where you are most vulnerable to the enemy’s temptations and discouraging lies and strengthen it.

(https://content.app-sources.com/s/16265172600299116/uploads/File_Uploads/Becky_Eldredge_re_Gallagher_14_Rules_of_Discernment-6760490.pdf, accessed 19 July 2025)

Summary

The goal of all that we have said today is simply to become attentive to the movement of the Holy Spirit in your life: through focusing on the fundamental purpose of your life, through frequent self-examination, by listening to your life, and by becoming aware of the times of consolation and desolation that we all experience. The Holy Spirit is the very presence of God in us, uniting us to Christ, presenting us to God our Father. And we want to be aware of what is happening so that we can cooperate with it. We end this course with the prayer we offered in the first class: Heavenly Father, fill me/us with your Holy Spirit. Amen.