APOSTLES ANGLICAN CHURCH

Fr. John A. Roop

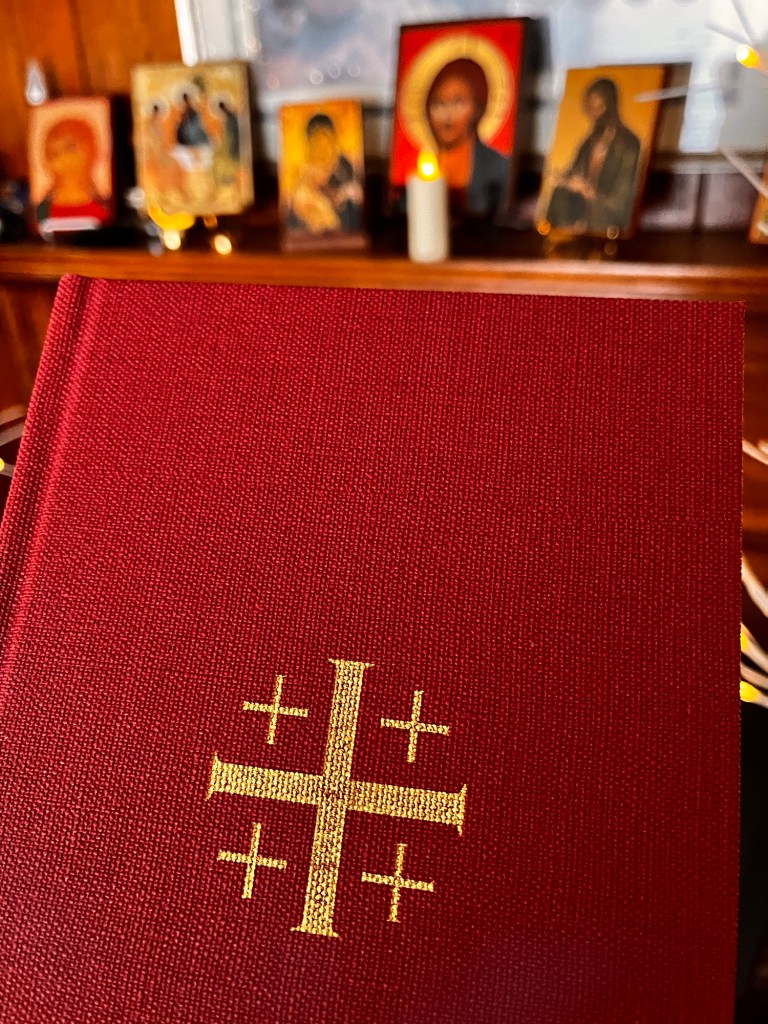

The Book of Common Prayer: Introduction

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

76. FOR GUIDANCE (p. 669)

Go before us, O Lord, in all our doings with your most gracious favor, and further us with your continual help; that in all our works begun, continued, and ended in you, we may glorify your holy Name, and finally, through your mercy, obtain everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

RECENTLY, I LISTENED to an episode of the Lord of Spirits podcast co-hosted by two Orthodox priests. One of them, in passing, expressed his conviction that all Christians should be Orthodox, that is, that all Christians should be members of the Orthodox Church. I have thought about that statement frequently since then; I’m still thinking about it as you can see. Here’s the question the podcast raised for me: As an Anglican priest, is it my conviction that all Christians should be Anglican? My answer is no. I stand with St. Paul here. He speaks of the Corinthian Church — or churches — as one body whose many members bring a variety of spiritual gifts to enrich the whole. To say that every bodily sense organ should be an ear, is to blind the body, to diminish it. I think the same holds true for the catholic/universal Church. To say that every Christian should be Orthodox or Roman Catholic or Anglican — or anything else — would be to deprive the Church of those distinctive spiritual gifts given to the various expressions of the one, holy, catholic, and Apostolic Church. My conviction is that Anglicanism brings some spiritual gifts and graces to the table that other expressions of the faith do not, or do not in the way and to the degree that Anglicanism does: likewise with Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. Each of these communions — each of these expressions of the faith — has the essential fullness of faith and practice, but has a different culture/ethos and expresses that faith somewhat different. Each has riches that the others lack. Each has errors that the others challenge. We need each other.

So, what does Anglicanism bring to the table? What is most distinctive or unique about Anglicanism? Let me approach this question backwards: What is not unique about Anglicanism? What do we share in common with the catholic/universal Church? Let’s return to the Book of Common Prayer (BCP 2019), specifically to the Fundamental Declarations of the Province, on pages 766. Consider the introductory paragraph and declarations 1 through 5.

[Review the Introduction and elements 1-5]

The introductory paragraph and the first five commitments of the Declarations may be summarized by a statement from Richard Hooker (1554-1600), one of the greatest classical Anglican theologians:

Anglicanism has no unique theology.

He meant by this, in the words of St. Vincent of Lerins (died c. 445), that we Anglicans believe that which has been believed “everywhere, always, and by all,” a faith given in the Scriptures, the Creeds, the Councils; a faith birthed and nurtured in the Sacraments of Holy Baptism and Holy Communion; a faith preserved and defended by godly Bishops. God forbid that we are novel in our doctrine. We hold to that faith, as Jude said, delivered once for all to the saints (Jude 1:3).

Now, back to the original question: If we have no unique theology, what, if anything, is distinctive about Anglicanism? Elements 6-7 of the Declarations answer that. We’ll read them as presented, and then I will summarize them.

6. the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) which embodies, and expresses as prayer and worship, the doctrine and discipline of the Anglican Church, and

7. the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion which resolve certain controverted doctrines by returning to the faith of the ancient Church, thereby eliminating certain medieval distortions and additions.

If you want to know what Anglicanism is about — what Anglicans believe, how Anglicans worship, in what manner Anglicans are formed — there is no better place to start — in fact, there is no other real place to start— than with the Book of Common Prayer. Ideally you would start with the Prayer Book as it is used in worship, through fellowship with an Anglican parish, which, of course, you are doing. For Anglicans, the BCP is second in importance only to Scripture and has been described as Scripture organized for prayer. It is God’s gift to the one, holy, catholic and Apostolic Church through the Anglican Communion. It is used by many Christians who are not and who never will be Anglicans.

What is the Book of Common Prayer? Let’s return to the the beginnings of the Church, to worship in the wake of Pentecost.

Acts 2:41–44 (ESV): 41 So those who received his word were baptized, and there were added that day about three thousand souls.

42 And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers. 43 And awe came upon every soul, and many wonders and signs were being done through the apostles. 44 And all who believed were together and had all things in common.

Notice the content and structure of apostolic worship: apostles’ teaching, fellowship, breaking of bread, and prayers. The earliest Christians gathered, listened to the Word of God through the Apostles, celebrated the Eucharist, and prayed. Does that pattern sound familiar? It is the service of Word and Table observed in Anglican churches worldwide each Sunday.

This Scripture gives us a normative pattern for worship — a structure — but not a detailed form or content. In the early days of the Church, such an outline was enough. The Apostles, and their direct disciples, were present to ensure consistency and orthodoxy among the churches. But, as the Church spread, it became more important to flesh out this outline, to put words and practices down in writing to preserve the one faith of the Church. By the second century, liturgies for baptism and Eucharist had been formalized and by the fourth century they were widespread. The undivided Church was a liturgical Church; in that way, faith and practice were preserved and passed down.

But, as typically happens, things became more, not less, complex — read that as needlessly complicated — with time. In the Roman church just before the Reformation began, the worship of the church required at least four large and costly books:

Breviary: Daily Office texts (seven or eight periods of prayer daily)

Missal: Eucharistic texts

Manual: Occasional Services texts (baptism, marriage, burial, etc.)

Pontifical: Episcopal (led by bishops) texts (ordination, confirmation, etc.)

Not only were these volumes too expensive for the masses, they were also complicated to use and written in Latin, a language few but clergy knew. So practically, the worship that should have been common to all God’s people had become the sole domain of clergy (the Eucharist) and monastics (the Daily Office). The people attended and watched worship, but did not understand or participate in it.

The Reformers, and especially the English Reformer Thomas Cranmer, saw this as a violation of biblical principles, namely that worship is the work of the people (liturgy), all the people. His great life’s work was the reclamation of worship for the people of God, and his solution to this problem was the Book of Common Prayer.

Take the four volumes required for worship in the Roman church, simplify them and purify them of medieval errors (restore ancient faith and practice), translate them into English, get them into the hands of the people: these are the ideas behind the Book of Common Prayer.

The Book of Common Prayer ensures that we are worshipping as the Church has done since its birth, but in a language and style appropriate for our culture and easily adaptable to other cultures without sacrificing orthodox faith and practice.

For more about this, and for an excellent historical overview of the Book of Common Prayer, I commend the Preface, pages 1-5, in the BCP 2019.

But, the Book of Common Prayer does even more than what we’ve mentioned. It functions as a regula — a rule of life — that structures and sanctifies our days, our weeks, our years, and the whole of our lives. Let’s turn to the Table of Contents. Look at the way this book helps sanctify our lives on every scale.

Daily: The Daily Office (Morning and Evening Prayer, Midday Prayer and Compline)

Weekly: Holy Eucharist

Yearly: Seasonal Greetings, Collects, and Special Liturgies, Calendar and Holy Days, Lectionaries

Life: Baptism, Confirmation, Matrimony, Birth/Adoption, Confession, Sickness and Recovery, Death

The Book of Common Prayer is a comprehensive guide and companion to the whole of life that teaches us how to live intentionally in the presence of God and in fellowship with our neighbors.

So, why the Book of Common Prayer?

It preserves and hands down the ancient and normative pattern of the worship in the Church, the liturgy: the Apostles’ teaching, the fellowship, the breaking of bread, and the prayers. It ensures order and consistency and truth in our worship.

It provides a rule of life — a companion and guide in our faith journey — that sanctifies our lives daily, weekly, monthly, and throughout the whole of life.

It forms us in the Word and in prayer by leading us substantially through the whole of Scripture each year and through the Psalter each month or bi-monthly, and by teaching us to pray the prayers of the Church.

The normative BCP dates from 1662. While it serves as the authoritative standard reference for our Province, few parishes actually use it for worship. In fact, there have been two major revisions of the BCP 1662 in the United States, one in 1928 and another in 1979. Our Province, the ACNA, published yet another revision in 2019, which raises questions: Why a new revision to the Book of Common Prayer? Why did the ACNA decide to publish a unique provincial BCP, instead of using an existing book?

There are several answers to these questions, and any complete answer would take more time than it’s worth in this class. So just a few, brief ideas will have to suffice.

Our Province spans North America: the United States and Canada. In the U.S. alone, there are several different prayer books in use: BCP 1928 (traditional Anglican), BCP 1979 (contemporary ecumenical), REC BCP, and even, rarely, the BCP 1662 (the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship). Canada has its own book, the BCP 1962. The hope is that the BCP 2019 will be so well accepted that it may become a standard for our province and bring us more substantially together around a single prayer book. No one is required to use this new revision, but Archbishop Duncan, the chair of the Liturgy Task Force which produced the revision, has said that one goal was to make the revision so beautiful that parishes would want to use it.

There was also the desire to produce a prayer book in keeping with the structure and traditional Anglican forms of the BCP 1662 (our provincial standard for classical Anglican faith and practice), but in contemporary language.

These are primary reasons for the revision.

Now to the book itself. Let’s turn to page 6, Concerning The Divine Service of The Church. Looking at this section will help us understand the actual layout/design of the BCP 2019. We will also refer to the Table of Contents.

The first paragraph defines the regular services of the church, those services which occur on a regular basis and which are for everyone: the Daily Office (Morning and Evening Prayer), the Great Litany, Holy Communion, Baptism, and Confirmation. If you look at the Table of Contents you will notice that these are the first services presented in the BCP, the most commonly used services right up front in the book. The Liturgy Task Force gave considerable thought to the physical layout of the BCP 2019 to make it logical and convenient to use.

The following four paragraphs give additional directions on how these regular services are used: part theology and part instructions.

The sixth paragraph mentions occasional services. As you might imagine, these are services that do not occur on a regular schedule, but rather on an as-needed basis. And some of them apply only to specific people, not to everyone. These are identified in the Table of Contents as Pastoral Rites and Episcopal Services. You can see that they follow the regular services in the layout of the book.

The Psalms are central to all our services; the Psalter is the prayer book and hymn book of Israel and thus of the Church. It seems fitting, then, that the Psalter is in the center of the physical layout of the BCP 2019.

Following the Psalter are the Episcopal Services, the services that are reserved to and conducted by the Bishop. The Bishop ordains, institutes the rector of a parish, consecrates a place of worship and dedicates many of its furnishings. You will have no need of these services unless you attend one of them. But, I still recommend reading through them; they contain important elements of Anglican theology.

Next come the Special Liturgies of Lent & Holy Week, services we use only once each year. They are placed toward the back of the back of the BCP.

Near the end of the BCP 2019 — where they are easy to find — are two sections you will use daily, if you regularly pray the Daily Office: Collects & Occasional Prayers and Calendars & Lectionaries.

Let’s begin with The Calendar of the Christian Year, on page 687. This section tells us what to do when, and how the church year is organized. [Review each section briefly and then the Calendar, p. 691 ff.]

The next major section is Sunday, Holy Day, and Commemoration Lectionary, p. 716 ff. Here are tables that provide the lectionary readings for each Sunday, Holy Day, and optional Commemoration. Paragraph two orients us to the table.

Next comes the Daily Office Lectionary, p. 734 ff, which, as the name implies, you will use every day is you pray the Daily Office. This section begins with instructions for the Psalter. There are two established patterns for praying the Psalter: a 30 day option (p. 735) and a 60 day option (p. 738 ff). [Explain the two options.]

The instructions for the Daily Office Readings begin on page 736. I recommend reading the two page introduction, pages 736-737, to understand the history and rationale for this lectionary. Again, there are two defined options for the Daily Office Readings: a one year cycle and a two year cycle. The second and the last paragraphs in the instructions define these two patterns. [Review these paragraphs.]

The tables of readings begin on page 738. [Demonstrate how this works by using today’s date.]

The final section in the BCP 2019 is Documentary Foundations, those documents which define the boundaries of our faith and practice. [Review the documents in this section.]

If you return to the Table of Contents you might notice that we have skipped one very important section in the Prayer Book: Collects & Occasional Prayers. We will address this section next week when we take a more detailed look at the regular services of the Church, particularly the Daily Office and Holy Eucharist.

Perhaps more than any other resource, the Book of Common Prayer defines both what the Anglican Church shares with other expressions of the Christian faith and what is distinctive about Anglicanism. It is Anglicanism’s unique gift to the Church universal. It is a treasure that will bring those who use it regularly and fully deeper and deeper into the heart of the faith: through participation with a parish; through Scripture, worship, Sacraments, prayer, and theology.

If you have questions about the BCP or about how to use it fully, please talk with one of our priests. We are always delighted to share this resource with others.