An Inductive Theology of Fasting

[A group of fellow Anglican priests asked me to offer a few pre-lenten observations on fasting. Following is the text of the brief presentation I made.]

I don’t think that Scripture contains an explicit theology of fasting. Instead, in both the Old and New Testaments, we see multiple examples of God’s people, and even pagans, actually fasting in a variety of circumstances and for a variety of reasons, and we are left to construct a theology inductively: from example to principle, from practice to theory. And it may be that it isn’t necessary or even possible to form a detailed theology of fasting; it may be enough to say that the example of Scripture — and the Church — tells us to fast under these circumstances, that it is somehow instinctive to man and pleasing to God. So, I thought to do a quick and partial survey of some examples of fasting in Scripture to see what we might glean.

It might, at first, seem like a stretch to say that the first example of fasting occurs in Eden, but I think the point can be made. God fills the garden with plants and trees from which man can freely eat. But, without explanation, God plants one tree — and points it out — from which man must not eat. It is this tree alone that creates the first fasting rule: total abstinence. The rule isn’t arbitrary: the tree is toxic to obedience, to relationship, and to life of man and to the state of the world. That it was a fast, and a difficult one, is seen from Genesis 3:6:

Genesis 3:6 (ESV):

6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate.

I don’t much care for steak, until all the Fridays in Lent, when I see that a steak is good for food, and a delight to the eyes (and nose), and to be desired to satisfy one’s stomach. I know how Eve felt. So, Adam and Eve broke the fasting rule with disastrous consequences. This is an example of perpetual, total abstinence because that which seems good and delightful to us is, instead, toxic. Since we don’t keep Kosher, food doesn’t fall into this category for us. But some forms of sexuality at all times and all forms of sexuality at some times do. Substance abuse does. Idolatry, too, and a whole list of practices that might momentarily delight us and ultimately destroy us. What God has forbidden we must fast from. There are other examples of perpetual fasts in Scripture. I’m thinking here of a perpetual Nazirite vow: a total abstinence from grapes, wine, and raisins. This fast was for setting oneself apart to God for some special purpose.

There are fasts in Scripture that seem almost instinctive. A person in deep sorrow simply has no appetite. That natural instinct may then be ritualized: fasting as a sign of mourning. So, upon learning of the lengthy exile of his people, for example, Daniel forgoes delicacies, meat, and wine to denote his mourning (Dan 10:1-3). People convicted of sin and compelled to repentance may be so focused on things spiritual, that things material — like eating — are pushed aside. Think here — among many other examples — of Nineveh upon hearing Jonah’s message of destruction (Jonah 3:6-10). From greatest to least, from man to beast, everyone fasted as a sign of repentance, fasted in sackcloth. And there is fasting as sacrifice, as an offering to God that we hope will make him propitious towards us. David fasted and prayed for God to have mercy on and spare his firstborn son from Bathsheba. That fast did not avail, and David abandoned it upon learning of the child’s death. These kinds of fasts — in times of sorrow, repentance, and intercession — seem to me to be instinctive. We somehow intuit that they are appropriate and then they become ritualized so that in such times we resort to them even if we might no longer be driven by instinct to do so.

Neither Jesus nor his disciples were known for fasting during the years of his ministry — in fact, to the contrary — but we do know of one instance in which he did fast. He fasted for forty days either before or during his time of temptation; the language is a bit ambiguous on the timing. This is an interesting episode that raises a fundamental question: Did Jesus fast to make himself weak and vulnerable or to make himself strong and fortified? I think the answer is yes to both. Certainly, forty days of fasting weakens the body and slows the mind, which may well be exactly what is needed in a moment of spiritual conflict. In a weakened state, I can no longer trust my own resources to save me; I must depend solely on the strength that comes from God. As St. Paul says, “When I am weak, then I am strong.” I know, from experience, that when I am facing a significant spiritual challenge, I should do so with fasting and prayer.

In at least two instances in the New Testament, fasting is associated with worship and discernment. Following his blinding outside Damascus and before the arrival of Ananias, Saul fasted from both food and water for three days (Acts 9:9). Certainly that was a period of profound discernment: What did the vision mean? What does his life look like going forward? What is he to do next? How will he — blinded as he is — fulfill any commission that the Lord Jesus gave him? This fasting, too, was almost certainly wrapped up with mourning and repentance and sacrifice. Then later, when Saul was in Antioch, the leaders there were fasting and praying — worshipping and seeking God’s will — when the Spirit set aside Barnabas and Saul for their first evangelistic mission (Acts 13:2): fasting for worship and discernment.

My sense of things — and that’s all it is, my sense of things — is that fasting is a God-given “instinct” in all these and other circumstances that we have ritualized, much like prayer for Anglicans — a natural instinct ritualized in the BCP and in a rule of life. And that brings me to the final “type” of fasting I want to mention.

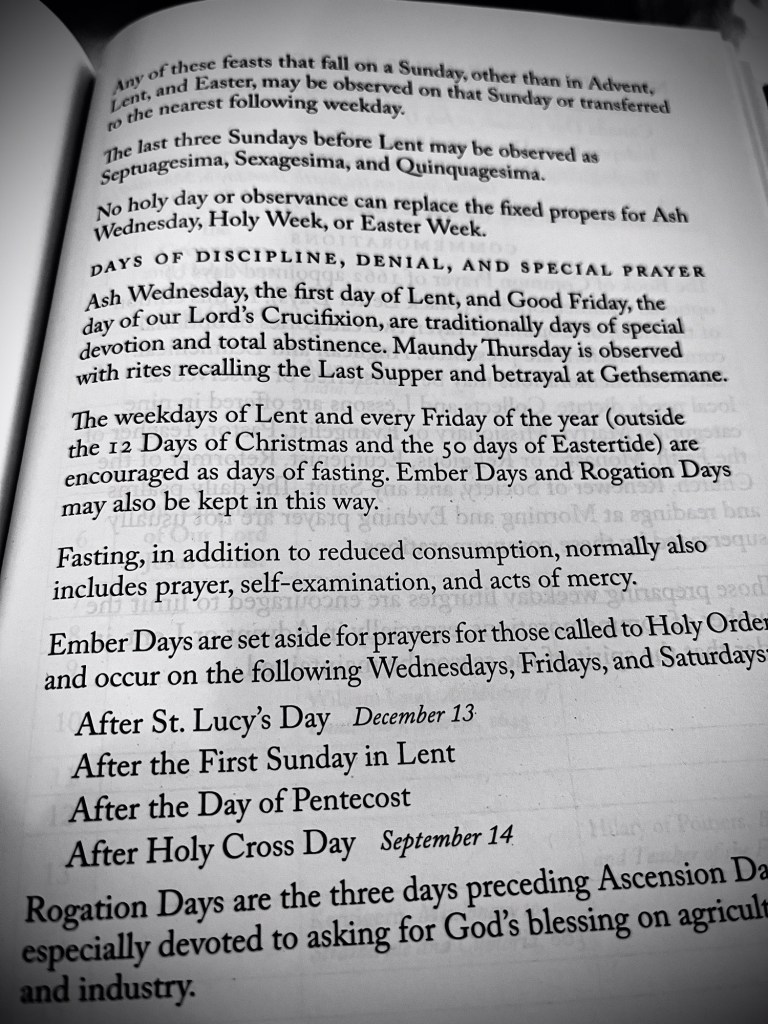

First, there is “rule of life” fasting: regular fasting undertaken as a spiritual discipline, like following the fasting rubrics in the BCP or like the fasting you may have undertaken in your rule of life. This is probably not instinctive, but rather is ritualized and regulated. What is the value of that? Well, there is the possibility that it is of little use at all. It can become like spiritual background noise that is just there but that hardly rises to the level of our attention; it is just something we do because our rule calls for it. It may not even be so stringent as to be noticeable. And, it is not for any particular purpose like mourning or repentance or discernment. But, if this regular fasting pinches a bit, it can remind us that we do need to mourn for the state of the world and the state of our souls — always; that we must be engaged in ongoing repentance for the sake of our salvation; that we are always engaged in spiritual combat beyond our own strength; and that we always need discernment to see as God sees.

Let me give an example of how this might work. You are probably familiar with the prayer of confession in the Daily Office in the BCPs 1662 and 1928. I will quote just the pertinent part:

ALMIGHTY and most merciful Father; We have erred, and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep. We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. We have offended against thy holy laws. We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; And we have done those things which we ought not to have done; And there is no health in us. But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us, miserable offenders (BCP 1928).

You get the phrase that was, lamentably, excised from the BCP 2019: miserable offenders. “Miserable” has nothing to do with how we feel when we pray the confession, but rather with our true state as we pray it. Here is an analogy that I read somewhere. Imagine a man in a train speeding along the track. He is having a perfectly pleasant experience, perhaps enjoying a good meal and conversation in the dining car. He feels anything but miserable. And yet, unbeknownst to him, there is another train on the same track barreling toward him in the opposite direction with another passenger also having a pleasant experience. Despite their feelings, they are both miserable, i.e., they are both in a pitiable and desperate state. What they need is something to alert them — and the two engineers! — to the truth. That’s what the words in the confession do and why their absence is damaging; they alert us to our true state, even if said routinely. And that is just what fasting as a spiritual discipline can do. It can alert us to the fact that we are miserable: that we need to mourn, that we need to repent, that we must not depend on our own strength in spiritual combat, that we need wisdom and discernment from above. The act of fasting as a discipline can actually awaken us to the fact that we need the fast more than we might have thought, for all the different reasons we see in Scripture.