Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John Roop

Hebrews 1-3: Jesus as the Superior Revelation

The Lord be with you.

And with your spirit.

Let us pray.

Almighty and everlasting God, whose will it is to restore all things in your well-beloved Son, the King of kings and Lord or lords: Mercifully grant that the peoples of the earth, divided and enslaved by sin, may be freed and brought together under his most gracious rule; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Introduction

To begin, a quote from C. S. Lewis:

Christianity, if false, is of no importance, and if true, of infinite importance. The only thing it cannot be is moderately important (C. S. Lewis, God In the Dock).

That is a classical and brilliant bit of Lewisian reasoning, but is it correct? From a theological perspective, I think it is. But, from a more existential perspective, from the perspective of lived experience, I’m not so sure. Let’s take it statement at a time.

First: Christianity, if false, is of no importance. That was the conviction of the new atheists championed by the Four Horsemen of that movement — Dawkins, Harris, Hitchens, and Dennett — and many others during their heyday in the decade and a half following September 11, 2001. But the new atheism proved to be not new at all, just warmed over ideas presented with sarcasm, bitterness, and mockery. It could not — and ultimately did not — stand up to scrutiny. But, more importantly, it could not provide a foundation for building a culture or a meaningful life. Now, some prominent atheist and agnostic thinkers — including Dawkins, historian Tom Holland, psychologist Jordan Peterson — conclude that all that is best in Western culture is absolutely dependent upon Christianity; some now even describe themselves as cultural Christians. So, even though they think Christianity is false, they think it is of great importance for culture building and stability and for the moral and ethical foundation of life.

Second: Christianity, if true is of ultimate importance. I suspect that many Christians — those who accept the truth of the faith — would agree wholeheartedly with that statement. But, would the evidence of their lives support their conviction? What does their actual practice and devotion suggest as their highest good: self, family, success, comfort, money, power, pleasure, honor, political party? Christianity, accepted as true, is still not always treated as of ultimate importance. Instead, the evidence suggests that it is the third option — the only one Lewis says in not viable — that is actually the one most nearly true: for many, Christianity, even accepted as true, is yet only moderately important. Lewis is perfectly logical and perfectly reasonable, but people do not readily follow the dictates of such logic. Lewis argues what should be, not what actually is.

Now, imagine being a first century Palestinian Jew presented with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. If the proclamation is false, it is of no importance at all, except perhaps in a negative sense; it may be blasphemous and misleading and worthy of opposition. That is certainly what Saul of Tarsus thought. But, what if on second or third hearing you find yourself believing it? What if you find your mind and heart opened to see Jesus as the messiah, as the fulfillment of the Covenants and the Law and the Prophets, the story of Israel brought to its proper conclusion? For those raised on the Shema — raised to love God with all one’s heart, soul, and might — then the Gospel might well be of ultimate importance and demand ultimate allegiance.

If so, how would that affect their lived experience? From what we can discern from historical writing, these Jewish Christians lived what we might call a double life, though to them it was just life; they were both orthodox Jews and faithful Christians. In fact, they were orthodox Jews precisely by being faithful Christians. That means that they would have maintained many of their Jewish customs and much of their Jewish worship. They would have kept kosher, circumcised their male children, observed the Sabbath, and worshipped in the Temple. But, they also would have worshipped with the church, likely in a home during the early years of the faith, on Sunday and perhaps at other times during the week. Those Christian gatherings would have included the Apostle’s teaching, the fellowship, the breaking of bread, and the prayers. At first, these would have been exclusively Jewish gatherings so that they were seen as simply an extenuation of Jewish life and worship. To get a sense of this integrated Jewish-Christian life, you might read the Benedictus (the Song of Zechariah) followed immediately by the Apostles Creed as we often do in Morning Prayer.

And that synthesis worked until it didn’t: until there grew increasing pressure from Rome to distinguish between Jews, an ancient and tolerated religion, and this upstart Christian group which was de-stablizing the Roman culture; until the larger Jewish community began to grow first skeptical and then hostile toward the Christians; until Gentiles began first to trickle in and then flood into the Church. So, pressures grew on the Jewish Christians to pick a side.

So, what were the options for a Jewish-Christian? Let me suggest three, based on Lewis’s trichotomy of no importance, ultimate importance, or moderate importance.

One might decide that the Gospel was not true after all and simply return to a full embrace of Second Temple Judaism sans Messiah. Christianity is false and is of no importance.

Or, one might decide that, since the Gospel is true, it is of ultimate importance and that full allegiance must be given to the Christian community. If it is no longer possible to maintain ties with those Jews who do not accept the Messiah, then so be it: as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord Jesus.

There is a third option: one could simply tone the Christian thing down a bit — stop talking so much about Jesus, stop going to the Sunday meetings, stop celebrating the Eucharist. It is not required to renounce Jesus, just to make him of moderate importance and to have one’s primary allegiance be with the Jewish community. That would really make life much simpler: the conflict with the Jewish community would end, the toleration from the Roman authorities would increase, and one could still be a Christian of sorts, just not fanatical, just not overtly. Of course, it is not far from this course to a total abandonment of the Christian faith.

It seems to be this latter group — those Jewish Christians who are tempted to see Jesus as only a moderately important add-on to Judaism — to whom the author of Hebrews addresses himself. His — and I am presuming that the author is male — his strategy is to show how Jesus is superior to the central elements of Judaism, how Jesus is the fulfillment of all the central elements of Judaism, and is thus of ultimate — not moderate — importance.

It would be interesting to explore some of the questions of authorship and dating surrounding this epistle, but we only have four class sessions, and it is more important, I think, to plunge headlong into the text letting this brief introduction suffice. I will simply say that God alone knows the author. To avoid the awkward wordiness of saying “the author of Hebrews” throughout these sessions, I will just say “Hebrews” or “the author.” The recipients are almost certainly Jewish-Christians in Palestine who are under a fair bit of pressure/persecution. The date of writing is almost certainly before the destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. since portions of the book assume Temple worship.

Just a note about what we can and cannot do in this class. We have only four weeks allotted to us, and that makes a detailed study of the whole of Hebrews impossible. So, instead, I will try to develop four major themes of the epistle that are, I think, true to its purpose and also meaningful for us in our context. That means that many of your favorite passages will lie unexplored — mine, too. That is regrettable, but also unavoidable. Think of this class as a preview to entice you into your own study of the epistle.

Hebrews 1-3: Jesus as the Superior Revelation

How can we know about God? In what ways has he revealed himself to us?

A good Second Temple Jew might have answered these questions by quoting Psalm 19:

1 The heavens declare the glory of God, *

and the firmament shows his handiwork.

2 One day speaks to another, *

and one night gives knowledge to another.

3 There is neither speech nor language, *

and their voices are not heard;

4 But their sound has gone out into all lands, *

and their words to the ends of the world.

5 In them he has set a tent for the sun, *

which comes forth as a bridegroom out of his chamber, and rejoices like a strong man to run his course.

6 It goes forth from the uttermost part of the heavens, and runs about to the end of it again, *

and there is nothing hidden from its heat.

7 The law of the Lᴏʀᴅ is perfect, reviving the soul; *

the testimony of the Lᴏʀᴅ is sure, and gives wisdom to the simple.

8 The statutes of the Lᴏʀᴅ are right, and rejoice the heart; *

the commandment of the Lᴏʀᴅ is pure, and gives light to the eyes.

9 The fear of the Lᴏʀᴅ is clean, and endures for ever; *

the judgments of the Lᴏʀᴅ are true, and righteous altogether.

10 More to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold; *

sweeter also than honey, than the drippings from the honeycomb.

11 Moreover, by them is your servant taught, *

and in keeping them there is great reward.

12 Who can tell how often he offends? *

O cleanse me from my secret faults.

13 Keep your servant also from presumptuous sins, lest they get the dominion over me; *

so shall I be undefiled, and innocent of great offense.

14 Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be always acceptable in your sight, *

O Lᴏʀᴅ, my rock and my redeemer (BCP 2019, pp. 289-290).

So, what are the two most fundamental sources of revelation we have? Nature and the Law, with the Law taken in a broad sense to mean God’s special revelation of himself to Israel in covenant, Exodus, Law, prophets — all the different means God used to make himself know to his people.

Let’s take these two, nature and Law, in turn. What can we know about God through nature? St. Paul takes up that question in Romans:

Romans 1:18–20 (ESV): 18 For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. 19 For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. 20 For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.

So, what does nature tell us about God? That God is, but that his existence is not like ours; his nature is divine, of a different order than ours. He is not directly visible to us, but we infer his attributes from what is seen. God is eternal and he is powerful. What we cannot know from nature is whether God is good or just or merciful or loving. Nature — red of tooth and claw — is ambiguous on all that. The evidence is so ambiguous to some that they reach a different conclusion about the existence of God entirely. Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist and one of the Four Horsemen of the New Atheists, wrote this in his book Out of Eden:

The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is at bottom no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.

Of course, St. Paul would contend that Dawkins knows better and is simply suppressing the truth. And, Dawkins himself acknowledges that he interprets nature this way in large part as a matter of preference; he prefers a natural explanation to a supernatural one.

So, we — at least the Jews — turn from the general revelation of nature to the specific revelation made through calling/election, covenant, Exodus, Law, prophets, all of which is summarized under the general heading of Law. This adds specificity to our understanding of God’s nature; we can now know him as good and just and merciful and loving and frightening and wrathful and jealous. In other words, we can know him not as a thing, but as a person, as the Person among persons.

That — the Law — is a great step forward in knowing about God. But even the Law placed God’s people at one degree of separation from God; there was always an intermediary between God and man, always a barrier of separation. You can think of the barrier as the sin of man or else as the righteousness of God, but either way the knowledge was direct but mediated. As we will see, the mediators were the angels. That is where Judaism leaves us. But what of Christianity?

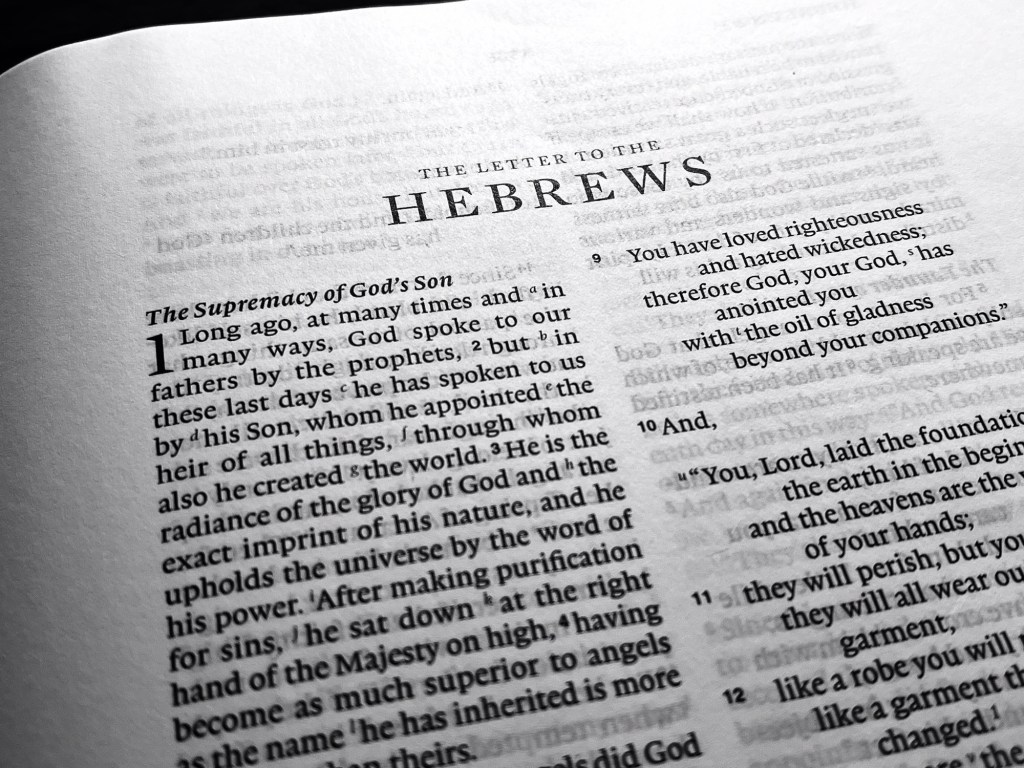

Hebrews 1:1–4 (ESV): 1 Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, 2 but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. 3 He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, 4 having become as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs.

In the past, God spoke many words in many ways to his people, summarized here under the term “the prophets.” But all of these communications were mediated, at one degree of separation at least. But now at last in the Son — in Jesus — we have the unmediated, unseparated perfect revelation of God himself to us: the radiance of the glory of God — the shekinah, the settling or dwelling place of God’s glory in flesh — and the imprint of his nature, the character of his Personhood. The one through whom the cosmos was created, the one who presently holds all things in being, the one who made purification for sins so that the wall of separation between God and man was eliminated, that one has made God known by making himself known. So, faith in Jesus offers a superior revelation than what is on offer in Judaism. Why embrace the shadow when we have the light? Why mess around with maps when we can live in the territory itself?

One way the author shows the superiority of the revelation we have in Christ is to insist that Christ is superior to the angels: “having become as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs.”

Hebrews 1:5–14 (ESV): 5 For to which of the angels did God ever say, “You are my Son, today I have begotten you”? Or again, “I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son”?

6 And again, when he brings the firstborn into the world, he says, “Let all God’s angels worship him.”

7 Of the angels he says, “He makes his angels winds, and his ministers a flame of fire.” 8 But of the Son he says, “Your throne, O God, is forever and ever, the scepter of uprightness is the scepter of your kingdom. 9 You have loved righteousness and hated wickedness; therefore God, your God, has anointed you with the oil of gladness beyond your companions.”

10 And, “You, Lord, laid the foundation of the earth in the beginning, and the heavens are the work of your hands; 11 they will perish, but you remain; they will all wear out like a garment, 12 like a robe you will roll them up, like a garment they will be changed. But you are the same, and your years will have no end.”

13 And to which of the angels has he ever said, “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet”?

14 Are they not all ministering spirits sent out to serve for the sake of those who are to inherit salvation?

Why all the talk of angels? Though it is not clear from Scripture itself, there was a common understanding among Second Temple Jews that God gave the Law to Moses not directly, but rather through the mediation of angels. That is the view of the Book of Jubilees, an apocryphal Jewish work from the first century B.C. or quite possibly earlier. That work was well known by the early Christians and Church Fathers, and the notion that angels were intermediaries between God and man is accepted and stated in Scripture: see Acts 7:53 (St. Stephen’s speech) and Galatians 3:19.

So, the author takes this tack: to show the superiority of the revelation of Jesus over that of the prophets it is enough to show that Jesus is a superior mediator over the angels. His argument has these points:

Jesus is the Son; the angels worship him and serve him.

The Lord is eternal in a way that the angels are not.

The Son sits at the right hand of God — the position of power and authority and rule — while the angels are his ministering spirits.

The author’s point is simple: a better mediator implies a better revelation. He continues this theme in what is for us chapter 2.

Hebrews 2:1–4 (ESV): Therefore we must pay much closer attention to what we have heard, lest we drift away from it. 2 For since the message declared by angels proved to be reliable, and every transgression or disobedience received a just retribution, 3 how shall we escape if we neglect such a great salvation? It was declared at first by the Lord, and it was attested to us by those who heard, 4 while God also bore witness by signs and wonders and various miracles and by gifts of the Holy Spirit distributed according to his will.

In Heb 2:1 we see a summary of the purpose of the epistle. If I may use anachronistic language, the author says, “The Christian revelation is superior to the Jewish revelation — as Jesus is superior to the angels — and you must not drift away from it.” We are back to where we started: this superior revelation cannot be merely moderately important. If Jews were accountable to God for keeping the Law mediated by angels, how much more will those who have received the revelation through Christ be accountable if they neglect it — relegate it to unimportant status?

Now it is as if the author anticipates some “push back” against his assertion that Jesus is superior to the angels. What is the apparently weak point in his argument? Jesus’s humanity and his suffering on the cross. He didn’t look superior to the angels and the notion of a suffering, crucified Messiah is foolishness to the Greeks and a stumbling block to the Jews.

This has always been a sticking point in the proclamation of Jesus. The author does not shy away from this objection but instead grasps the nettle with this argument.

It is true that we did not see Jesus in his glory, nor do we see clear evidence of his present reign over all things. Instead, we saw his humanity in which he was made, for a time, lower than the angels so that he might be the perfect representative of mankind, so that he might taste death for everyone and destroy death, so that he might sanctify mankind, and so that he might become the great high priest for those whom he calls brothers. This last notion of the high priest is a preview of coming attractions.

So, the author argues that what we saw of Jesus is fitting, that it makes narrative sense: the Son of God becoming fully human — apart from personal sin — to save humans, and then himself to be exalted to God’s right hand where he continues to intercede for those he calls brothers. There is nothing quite like that is Judaism.

Now, the author has established that Jesus is superior to the angels. If the Law — the revelation — they mediated is worthy of attention, then how much more the revelation given in and through the Son. But there is a more towering presence in the history of God’s revelation to his people, more central than angels, the most prominent figure in Jewish thought: Moses. How does Jesus fair in comparison to Moses?

Hebrews 3:1–6 (ESV): Therefore, holy brothers, you who share in a heavenly calling, consider Jesus, the apostle and high priest of our confession, 2 who was faithful to him who appointed him, just as Moses also was faithful in all God’s house. 3 For Jesus has been counted worthy of more glory than Moses—as much more glory as the builder of a house has more honor than the house itself. 4 (For every house is built by someone, but the builder of all things is God.) 5 Now Moses was faithful in all God’s house as a servant, to testify to the things that were to be spoken later, 6 but Christ is faithful over God’s house as a son. And we are his house, if indeed we hold fast our confidence and our boasting in our hope.

Let’s paint this picture in broad strokes. Think of God’s people — first Israel, later the Jews, and now the Jewish Christ-followers — as a household, an extended family. The household needed a patriarch: someone to care for it, provide for it, protect it. The paradigm of that patriarch under the Law was Moses. And yet, he wasn’t the patriarch — the father — in the full classical sense for one primary reason: the household was not his. He didn’t create it; it didn’t belong to him. As Moses often reminded God — particularly when he was weary or disgruntled — the people were God’s people, God’s burden to bear. So, what then was Moses’ position in the household? He was a faithful servant, a surrogate for the Patriarch, and he is worthy of honor for his faithful service.

But, there is a new household now, visibly smaller but potentially much more expansive — the household of those faithful Jews who follow Jesus. Who is the patriarch of this family? Not Moses, but Jesus. It is God — and remember that Jesus is the Son of God, is God incarnate — who has created this household. The Messiah/Christ is the faithful patriarch of it not as a servant, but as the Son, not as a surrogate for the patriarch, but as the patriarch himself. Therefore, Jesus is counted worthy of more glory than Moses.

The blessing of being part of this household comes with a caution, with a warning: And we are his house, if indeed we hold fast our confidence and our boasting in our hope (Heb 3:6b). Membership in the family is conditional.

The author reminds his readers that this same conditional membership obtained with Israel under Moses. Those who hardened their hearts in the wilderness, those who rebelled and provoked the Lord, died in the wilderness and did not enter the promised rest (see Heb 3:7-11). And that is a cautionary tale for those who have begun to follow Christ but are now look backward longingly toward Judaism as the Hebrews looked back longingly toward Egypt:

Hebrews 3:12–15 (ESV): 12 Take care, brothers, lest there be in any of you an evil, unbelieving heart, leading you to fall away from the living God. 13 But exhort one another every day, as long as it is called “today,” that none of you may be hardened by the deceitfulness of sin. 14 For we have come to share in Christ, if indeed we hold our original confidence firm to the end. 15 As it is said, “Today, if you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts as in the rebellion.”

Stay the course. Do not let Jesus become only moderately important or, worse still, of no importance whatsoever. What you have in Jesus is vastly superior to what you seem to have left behind: Jesus is superior to the angels, superior to Moses, and the household you have entered is superior to the household you left behind.

Conclusion

So, what does this have to do with us?

The great temptation of the world, the flesh, and the devil is not so much focused on getting us to renounce Jesus entirely, it seems to me, but rather on getting us to relegate Jesus to the moderately important category, on getting us to build our lives around something or someone else and then fitting Jesus into our lives when and where and if it is convenient. So, my focus is on building my career, raising my family, checking off items on my bucket list — all while affirming my faith in Jesus, of course, and even practicing that faith when it doesn’t interfere with my career, my family, my bucket list. It is not that these other things are bad — angel intermediaries weren’t bad, Moses wasn’t bad, Israel wasn’t bad — but rather that they are not ultimate. The challenge is to recognize Jesus as superior to all things and to let that recognition shape our lives. As C. S. Lewis wrote:

The longer I looked into it the more I came to suspect that I was perceiving a universal law… The woman who makes a dog the centre of her life loses, in the end, not only her human usefulness and dignity but even the proper pleasure of dog-keeping. The man who makes alcohol his chief good loses not only his job but his palate and all power of enjoying the earlier (and only pleasurable) levels of intoxication. It is a glorious thing to feel for a moment or two that the whole meaning of the universe is summed up in one woman — glorious so long as other duties and pleasures keep tearing you away from her. But clear the decks and so arrange your life (it is sometimes feasible) that you will have nothing to do but contemplate her, and what happens?

Of course this law has been discovered before, but it will stand re-discovery. It may be stated as follows: every preference of a small good to a great, or partial good to a total good, involves the loss of the small or partial good for which the sacrifice is made.

Apparently the world is made that way… You can’t get second things by putting them first; you can get second things only by putting first things first (C. S. Lewis, “First and Second Things,” God in the Dock (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1970), pp. 278-280).

You may know that I am critical of the theology expressed in many old hymns and the lack of theology expressed in most new ones. But there is an old American Spiritual I first heard sung by Fernando Ortega that summarizes the purpose of this portion of Hebrews quite well. The very simple chorus says:

Give me Jesus.

Give me Jesus.

You can have all this world,

But give me Jesus.