I write about illness from a state of good health, at least to the best of my knowledge. And that makes the writing both difficult and necessary. It is difficult because several people whom I love dearly are now facing health crises, and I fear lest they misinterpret what follows as callous. It is anything but. I share their burdens as I can, which primarily means through prayer. But, I am convinced that the type of observations which follow may best be written from the sidelines of suffering, as it were, in preparation for the real thing to come or else having come through the crucible of suffering. I suspect the three young men were able to praise God in the midst of the seven times hotter furnace only because they had praised him in better times and had worked through the consequences of doing so before Nebuchadnezzar erected his statue and demanded worship on pain of death. I want to think through the matter of illness clearly now so that when my time comes, as I suspect it will, I am not caught unawares. And, I hope that by the mercies of God, those who are in the thick of things right now might find some comfort here.

A priest is not a medical doctor, though he is most certainly a physician of souls and bodies. His training and tools — both diagnostic and treatment — differ from those of medical doctors. In his “little black bag” the priest carries not a stethoscope nor a sphygmomanometer but rather a Prayer Book and a Bible, an oil stock, a stole, and perhaps the Sacrament. His treatment includes prayer with anointing and laying on of hands, the Rite of Reconciliation (confession) with absolution, spiritual counsel and comfort, and perhaps the Holy Eucharist. While a medical doctor might speak of infections, cancers, and physical deterioration, a priest might speak of trials, sin, and passions. Priests do not — should not and must not — pit themselves against medical doctors or eschew the medical arts. Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) expresses the proper synergistic relationship of priest and physician, of prayer and medicine:

38 Honor physicians for their services, for the Lord created them; 2 for their gift of healing comes from the Most High, and they are rewarded by the king. 3 The skill of physicians makes them distinguished, and in the presence of the great they are admired. 4 The Lord created medicines out of the earth, and the sensible will not despise them. 5 Was not water made sweet with a tree in order that its power might be known? 6 And he gave skill to human beings that he might be glorified in his marvelous works. 7 By them the physician heals and takes away pain; 8 the pharmacist makes a mixture from them. God’s works will never be finished; and from him health spreads over all the earth. 9 My child, when you are ill, do not delay, but pray to the Lord, and he will heal you (Sirach 38:1-9, Holy Bible with Apocrypha, ESV).

We priests and our parishioners pray for the medical professions:

Almighty God, whose blessed Son Jesus Christ went about doing good, and healing all manner of sickness and disease among the people: Continue in our hospitals his gracious work among us [especially in __________]; console and heal the sick, grant to the physicians, nurses, and assisting staff wisdom and skill, diligence and patience; prosper their work, O Lord, and send down your blessing upon all who serve the suffering; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (BCP 2019, p. 661).

And, as a priest is not a medical doctor, it is equally true that a doctor is not a priest, though the Enlightenment and Modernity Projects embued them with a semi-divine aura of those who “put a stopper in death.” The recent pandemic reinforced this doctorism for some and debunked it for others.

Patients often ask medical doctors questions that begin with “what” or “how” or even “when;” the questions asked of priests often begin with “why.” The medical doctors are questioned about physiology and treatment, the priests about theology. Mystery obtains in both areas, though I suspect that medical training prepares the physicians of bodies to answer the questions posed to them better than does the training of priests. God help us if it is not so; God help us if it is so.

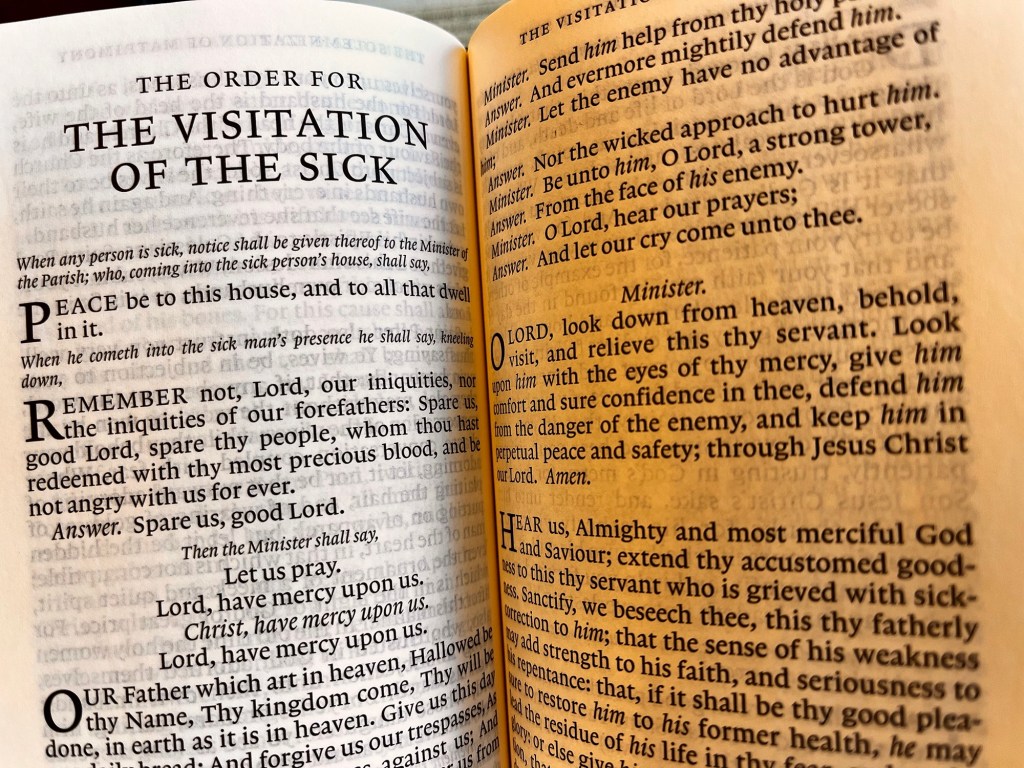

The Book of Common Prayer provides Rites of Healing and prayers for the sick. Since these rites and prayers are reflections on and applications of Scripture arranged for prayer and worship and pastoral care, one might expect to find in them a biblical theology of sickness and healing and perhaps even an answer to those questions that begin with “why.” Alas, that is not the case of late; no clearly articulated spirituality of illness and healing is found in such modern revisions of the Prayer Book as the BCP 1928 and the BCP 2019. Fortunately, the BCP 1662, “a standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline” (Fundamental Declarations of the Province (6), BCP 2019, p. 767) supplies what is otherwise lacking. These words come from another time, from a different context, from a world in which priests and prayer were perhaps more intimately associated with healing than were physicians and medicine. The words are strange to our ears and the theology is perhaps an affront to both modern hearts and minds formed by the Enlightenment project — at least initially. But this is the wisdom of our fathers and mothers, and it is worthy of both respect and consideration.

Soon after entering the house of the sick the priest using the BCP 1662 offers this prayer:

HEAR US, almighty and most merciful God and Saviour. Extend thy accustomed goodness to this thy servant, who is grieved with sickness. Sanctify, we beseech thee, this thy fatherly correction to him, that the sense of his weakness may add strength to his faith, and seriousness to his repentance, that, if it shall be thy good pleasure to restore him to his former health, he may lead the rest of his life in thy fear and to thy glory; or else give him grace so to take thy visitation, that after this painful life is ended, he may dwell with thee in life everlasting, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (The 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition, InterVarsity Press (2021), p. 325, see end note 1).

Following the prayer, the priest exhorts the sick person with these or similar words:

DEARLY beloved, know this, that almighty God is the Lord of life and death, and of all things pertaining to them, such as youth, strength, health, age, weakness, and sickness. Wherefore, whatsoever your sickness is, know you certainly that it is God’s visitation. And for whatsoever cause this sickness is sent unto you — whether it be to try your patience, for the example of others, and that your faith may be found in the day of the Lord laudable, glorious, and honourable, to the increase of glory and endless felicity; or else it be sent unto you to correct and amend in you whatsoever doth offend the eyes of your heavenly Father — know you certainly that if you truly repent you of your sins, and bear your sickness patiently, trusting in God’s mercy for his dear Son Jesus Christ’s sake, and render unto him humble thanks for his fatherly visitation, submitting yourself wholly unto his will, it shall turn to your profit, and help you forward in the right way that leadeth unto everlasting life (ibid, p. 326, see end note 2).

There is a depth of theology in this prayer and in this exhortation. It begins with a conviction of the sovereignty of God, “the Lord of life and death, and of all things pertaining to them” including health and sickness. The sick person is not theologically abandoned to the accidents and incidents of chance; rather, sickness and health, life and death are in the hands of God and his accustomed goodness: “whatsoever your sickness is, know you certainly that it is God’s visitation.” Whether this is a comforting or disconcerting assertion perhaps depends on one’s understanding of the nature of God. That it is intended for comfort is made clear in the assertion that one is in the “hands of God and his accustomed goodness.” It certainly challenges the modern mind to include illness within the loving care of God, to understand that illness might indeed be a blessing and a holy correction meant to strengthen faith and give seriousness to repentance, to lead to a holy life or else to a holy death.

As to why this sickness has occurred — and that is so often the pressing question — the exhortation offers several possibilities: as a test of patience; as an example to others; to make one’s faith laudable, glorious, and honourable; to increase one’s reward of glory and felicity; or as a correction. There is no reason to believe this list is exhaustive, but it is univocal; God intends this and every illness for one’s good in this age and in the age to come, intends illness for one’s spiritual profit.

How then is the sick person to cooperate with God to ensure that God’s visitation of illness accomplishes that for which it was intended? Repent of sins, bear sickness patiently, trust in God’s mercy, render thanks to God even for the illness — Glory to God for all things (Chrysostom) — and submit wholly to God’s will.

The language of sickness as God’s visitation, of sickness as something sent, is jarring to our modern sensibilities. The notion of God as the causal agent of illness is, perhaps, a theological step too far for many — but surely not the notion of God as the redemptive agent of illness. If it is too much to say that God visits us with illness, surely we can maintain that God visits us in and through, in the midst of, illness. Surely we can believe that God forms us — perfects us — through illness just as Jesus was perfected through suffering (Heb 2:10). Surely we can use illness as an impetus to repent, to amend our lives, to give glory to God through our patient endurance and submission to his will. Surely we can begin to move our questions beyond Why? to What is God doing here? and How might I, in cooperation with God, use this illness for my spiritual welfare?

Can we hear these words? Can we bear this theology? Can we who have, perhaps unwittingly, embraced a materialist attitude toward illness dare acknowledge its spiritual dimension? These are difficult words; perhaps that, along with the West’s increasing “faith” in medical science and technology, explains why this theology of illness disappeared from the Book of Common Prayer. But these are gracious words also, words that assure us that God is not absent from our most difficult moments; that God is resolutely acting for us and for our salvation in and through our most difficult moments; that meaning can be found, and glory, in our most difficult moments; that the answer to the questions that start with “why” are always “because God loves us.”

END NOTES:

- While a form of this prayer is retained in both the BCPs 1928 and 2019, both are reduced in theological content:

HEAR us, Almighty and most merciful God and Saviour; extend they accustomed goodness to this thy servant who is grieved with sickness. Visit him, O Lord, with thy loving mercy, and so restore him to his former health, that he may give thanks unto thee in thy holy Church; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (BCP 1928, p. 309).

Sanctify, O Lord, the sickness of your servant N., that the sense of his weakness may add strength to his faith and seriousness to his repentance; and grant that he may live with you in everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen (BCP 2019, p. 233). - No such exhortation is present in either the BCPs 1928 or 2019.