Apostles Anglican Church

Fr. John A. Roop

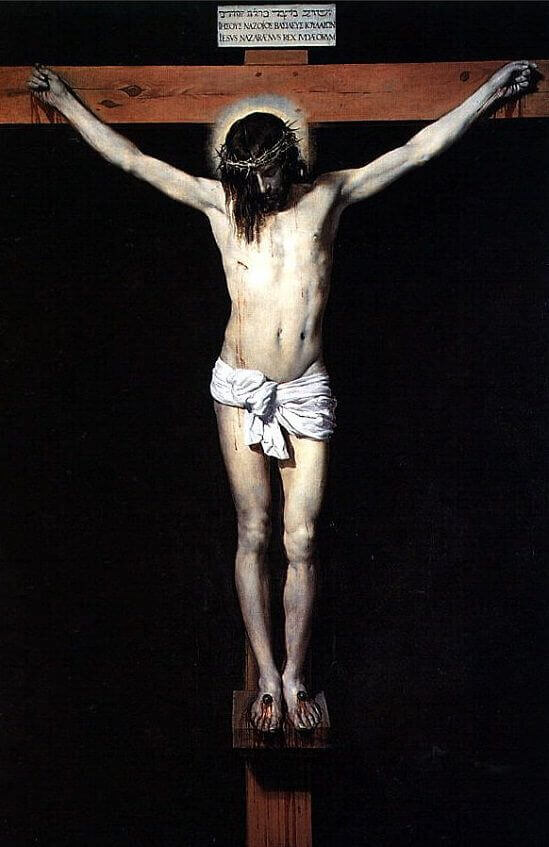

Holy Cross Day (14 September)

(Is 45:21-25 / Ps 98 / Phil 2:5-11 / John 12:31-36a)

Collect

Almighty God, whose Son our Savior Jesus Christ was lifted high upon the cross that he might draw the whole world to himself: Mercifully grant that we, who glory in the mystery of our redemption, may have grace to take up our cross and follow him; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

Preface of Holy Week

Through Jesus Christ our Lord. For our sins he was lifted high upon the Cross, that he might draw the whole world to himself; and by his suffering and death he became the author of eternal salvation for all who put their trust in him.

Both here and in all your churches throughout the whole world,

we adore you, O Christ, and we bless you:

because by your holy cross you have redeemed the world.

Matthew 24:1–2 (ESV): 24 Jesus left the temple and was going away, when his disciples came to point out to him the buildings of the temple. 2 But he answered them, “You see all these, do you not? Truly, I say to you, there will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.”

It is thought that Jesus spoke these words on Tuesday of Holy Week as a prelude to his Mount of Olives Discourse, the great apocalyptic prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem and possibly of the end of this age.

“There will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.” Forty years: that’s all it took for the fulfillment of this prophecy. Responding to a Jewish rebellion, the Roman army besieged Jerusalem on 14 April in 70 A.D. The city fell within four months, and by 8 September the Roman general Titus — soon to be Emperor — had leveled the city and the temple to rubble: not one stone left upon another, just as Jesus had said.

Some sixty years later, a new Emperor Hadrian set about rebuilding Jerusalem as a Roman City, Aelia Capitolina. His construction drastically altered the landscape of the city and covered over many of the sites holy to Christians, Calvary and the Holy Sepulchre among them. That was no great loss for the Romans, of course, until nearly two centuries later when Constantine converted to Christianity and made it first a tolerated and then a favored religion. The holy sites in Jerusalem, he felt, needed churches to mark them, to serve as sites for pilgrimages. First though, he had to relocate them. None was more important than Calvary.

Constantine’s mother Helena was a devout Christian and a godly woman. The early Church historian Eusebius wrote this about her:

Especially abundant were the gifts she bestowed on the naked and unprotected poor. To some she gave money, to others an ample supply of clothing; she liberated some from imprisonment, or from the bitter servitude of the mines; others she delivered from unjust oppression, and others again, she restored from exile. While, however, her character derived luster from such deeds … , she was far from neglecting personal piety toward God. She might be seen continually frequenting His Church, while at the same time she adorned the houses of prayer with splendid offerings, not overlooking the churches of the smallest cities. In short, this admirable woman was to be seen, in simple and modest attire, mingling with the crowd of worshipers, and testifying her devotion to God by a uniform course of pious conduct” (The Life of Constantine, XLIV, XLV).

Constantine tasked his pious mother with finding the holy sites of Jerusalem, chiefly Calvary. Stories about how she did this abound, but there are two I particularly like. While searching for Calvary, Helena noticed a large patch of an aromatic herb unknown to her. She felt compelled to dig in that spot and there she uncovered the wood from three separate crosses, perhaps those of the two thieves and Jesus. As an aside, that herb is what we call basil, from the Greek basileus meaning king. Many churches — mainly Orthodox churches — are decorated with basil plants in observance of Holy Cross Day.

So far, so good; Helena apparently had discovered Calvary and wood from three crosses. But which one was the true cross of Christ? A woman suffering from a terminal illness was brought to the spot and asked to touch the wood from each of the crosses in turn. When she touched the wood of the last one, she was miraculously healed; that must be the true cross of Christ. And that was the beginning of the veneration of the Holy Cross of our Lord Jesus. The church built on that site to house the cross was completed on 13 September 335 — 1688 years ago today — and formally dedicated the next day, 14 September, which we now observe as Holy Cross Day.

In one sense, it is somewhat odd that the Anglican Church would mark this day at all, since at its heart lies a relic, a piece of wood that the faithful venerate. A fifth century account gives this description of the service of veneration of the cross in Jerusalem.

A coffer of gold-plated silver containing the wood of the cross was brought forward. The bishop placed the relic on the table in the chapel of the Crucifixion and the faithful approached it, touching brow and eyes and lips to the wood as the priest said (as every priest has done ever since): “Behold, the Wood of the Cross” (Catholic News Agency, https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/resource/56094/the-veneration-of-the-cross, accessed 9/6/2023).

Such a practice would have been anathema to the English Reformers as stated in The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion:

XXII. OF PURGATORY

The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory, Pardons, Worshipping, and Adoration, as well of Images as of Reliques, and also Invocation of Saints, is a fond thin vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God (BCP 2019, p. 780).

And yet, here we are — good Anglicans — observing Holy Cross Day, a “red letter day” on our church calendar. We do so in our public worship, in our Common Prayer, not by venerating a physical representation of the cross — though some do that also — but rather by reflecting on the role of the cross in the great narrative of our redemption.

It is a strange sort of faith that makes an instrument of ridicule and torture, that makes the weapon used by “church and state” to murder its founder and god, the focal point of its redemption story. St. Paul understood the strangeness, the scandal of the cross which he described as a stumbling block (σκάνδαλον) to the Jews and as folly to the Gentiles (cf 1 Cor 1:23). Yet the cross is inescapable in our faith. We are not ashamed of it; it is the most exalted and ubiquitous symbol of our faith. But why? Why is the cross so central to our faith?

There are many ways to frame an answer to that question, but at the heart of every answer lies this: the cross is God’s solution to the existential crises of fallen humanity, to the crises that threaten our very existence. What are these crises? Again, there are many ways to frame an answer to that question, but all the ways must include sin, bondage, and death. This unholy trinity is the problem to which the cross is the answer.

When we think about sin, we might think only in terms of violating a commandment of God. And, while that is true, it is true only in a secondary way. The breaking of the commandment is the visible part of the iceberg. But, like the iceberg, sin is more vast, more hidden, and far more dangerous than what is seen. Genesis, in the first use of the word sin, presents sin as a power that seeks to destroy man (Gen 4:6-8). St. Paul presents sin as something indwelling man, preventing him from doing what he knows to be right and compelling him to do that which is contrary to God (Rom 7:15 ff), a passion — what we might call an addiction — that assumes control over our lives and destroys us. Sin is a power, external and internal, which rules over us and compels us away from God. And we are powerless over it.

But, the cross is God’s solution to sin. Hear St. Paul, again to the Romans:

Romans 6:3–14 (ESV): 3 Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? 4 We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.

5 For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. 6 We know that our old self was crucified with him in order that the body of sin might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer be enslaved to sin. 7 For one who has died has been set free from sin. 8 Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. 9 We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. 10 For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. 11 So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus.

12 Let not sin therefore reign in your mortal body, to make you obey its passions. 13 Do not present your members to sin as instruments for unrighteousness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life, and your members to God as instruments for righteousness. 14 For sin will have no dominion over you, since you are not under law but under grace.

The cross is God’s solution to the problem of sin.

Sin is not the only problem for which the cross is the answer; there is also bondage. Our sin enslaves us to Satan and the fallen powers. One of the central themes of Scripture — seen throughout the Old Testament and culminating in the cross — is God’s acts of redemption — of liberation — for his people. In Egypt, the Hebrews were enslaved to the fallen powers, both Pharaoh and the false gods of Egypt, and were powerless to extricate themselves. It took a mighty act of God — his mighty hand and outstretched arm — to deliver his people from bondage. The sacramental participation in that act of liberation was, and is for the Jews, the Passover meal. And it was the Passover meal that provided the context for the Last Supper, for the Sacrament of Holy Eucharist that Jesus instituted on the night before he died for us. There is a straight line from the liberation from the fallen powers in the Exodus to the liberation from the fallen powers in the cross. Redemption is the word commonly employed in Scripture for this liberation, as St. Paul writes to the Colossians:

Colossians 1:13–14 (ESV): 13 He has delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of his beloved Son, 14 in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.

The cross is God’s solution to human bondage to the fallen powers.

Lastly, the cross is God’s solution to death. In the Garden, God warned Adam of the consequence of disobedience — not the punishment, but the consequence:

Genesis 2:15–17 (ESV): 15 The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it. 16 And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, “You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, 17 but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.”

Adam ate, and in that day something in him died, as symbolized by his exile from Eden. And we — all of us from that moment forward — inherited death from Adam, the head of our race. But, listen again to St. Paul to the Corinthians:

1 Corinthians 15:1–5 (ESV): 15 Now I would remind you, brothers, of the gospel I preached to you, which you received, in which you stand, 2 and by which you are being saved, if you hold fast to the word I preached to you—unless you believed in vain.

3 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.

1 Corinthians 15:21–26 (ESV): 21 For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. 22 For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive. 23 But each in his own order: Christ the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. 24 Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. 25 For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. 26 The last enemy to be destroyed is death.

Christ died, crucified on a cross. Christ was buried, laid in a borrowed tomb. Christ rose on the third day. We have died with Christ, our body of sin crucified with him. We have been buried with him in the water of baptism. And we will rise with him, for death no longer has dominion over him. By him, with him, and in him death no longer has dominion over us.

The cross is God’s solution to the problem of death.

Why this feast day, Holy Cross Day? Because the cross is the focal point of all things in heaven and on earth. Because the cross is God’s solution to sin, bondage, and death. Because the cross is our salvation.

Both here and in all your churches throughout the whole world,

we adore you, O Christ, and we bless you:

because by your holy cross you have redeemed the world.

Amen.